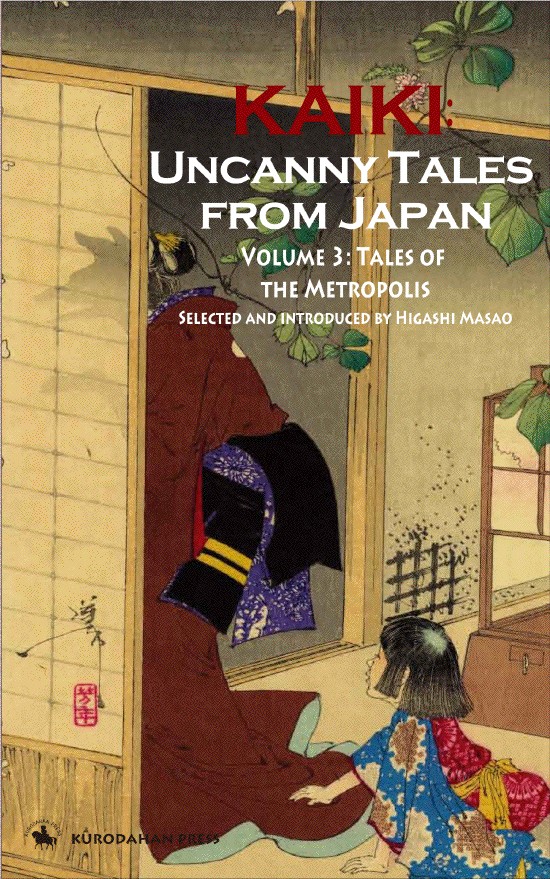

This is the third volume of Kurodahan’s “Kaiki” series – eerie supernatural stories from Japan, translated into English for the first time. The first one dealt with old Edo, the second dealt with the countryside, this one deals with city life.

This is the third volume of Kurodahan’s “Kaiki” series – eerie supernatural stories from Japan, translated into English for the first time. The first one dealt with old Edo, the second dealt with the countryside, this one deals with city life.

City-themed horror tales will probably always be with us. Humans evolved in troupes of around 50, and many of us still feel a fundamental “wrongness” about cities that no amount of indoor plumbing will shake. Some people feel that they’re not fitting in, that they’re alienated and alone. Others feel that they’re fitting in too well – losing their identity, and becoming another bee in the hive. Uncanny Tales 3 has takes on both these themes, and many more.

There’s a lot of good things here, but three stories stand out as more than good. The first is “The Face”, by Tanizaki’s Jun’ichiro. A story within a story, it’s deep and metafictional, but also disturbing and grotesque. A bizarre art film is being released, but the lead actress cannot recall having starred in it. It features her opposite an extremely deformed man with a cancerous second face, a face that couldn’t possibly have been added in with special effects. The story is intense and pacey, and although it was written in 1918, doesn’t seem at all dated or old in its treatment of the new technology of film and permanent recordings, and what it could mean if they don’t seem to match up to reality.

“Doctor Mera’s Mysterious Crimes” finds Edogawa Ranpo behind the helm of a powerful detective/urban horror hybrid story about a doctor who kills without leaving a trace of his presence behind. Virtually nobody writes psychological scares, like Ranpo, and this is him at his best, or close to it. The story grows ridiculous, but Ranpo’s mastery of mood and tension makes it a flavour of ridiculous we can swallow.

Yamakawa Masao’s “The Talisman” comes from 1960, as the Golden Sixties were just beginning. This story tackles the darker side of that period, namely the idea that the rising yen wasn’t lifting Japan’s people along with it, and that Japan had little use for human beings beyond their services to business and industry. The story involves a man returning home, and discovering that another man is already there, and is living his life. The story contains some more complications beyond that (some of them necessary, some of them not), but the crux of the tale is disturbing: is it possible for a man to be completely interchangeable, so that he can be replaced by another without anyone noticing the difference?

Higashi Masao provides an introduction, explaining the role and importance of “Kaiki” tales, as well as what makes Japan’s take on creepy stories unique. Basically, being Japanese is to have unease in your bones from cradle to grave – the island chain is under permanent threat from fire, from water, from earthquakes, et cetera. It might be easy to feel that this lifestyle is transient and short-lived, and maybe so, but the Japanese experience can be written down in books, which last forever. If we want them to.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.