Imagine waking up, and you’re not alone. There’s a thing with you, very close. You can’t see it or touch it. It’s in your head.

With dawning horror, you become conscious of the pulsating wormlike mass twisted right through the center of your brain. It’s infesting you like a cordyceps parasiting a spider – running man-in-the-middle attacks on all your senses and limbic network. It’s intimately a part of you. You sense intelligence, and malevolence, and tension, as though its a coiled spring, ready to discharge kinetic energy.

What are you? You ask the presence, although there is no answer. Just snuffling breath, hot and excited.

You go about your day with this alien thing inside you, itching like a tangled pile of wet hair. At the day’s end, the mass seems heavier, denser, more substantial. You are incubating it. You’re a shell. It’s larvae.

The parasite doesn’t affect your behavior, but you are nevertheless worried. What does it want? Why won’t it talk? It’s just there: staring at the world through your eyes, as if seeking some sign, some augury. It knows its time will soon come.

It’s waiting.

* * *

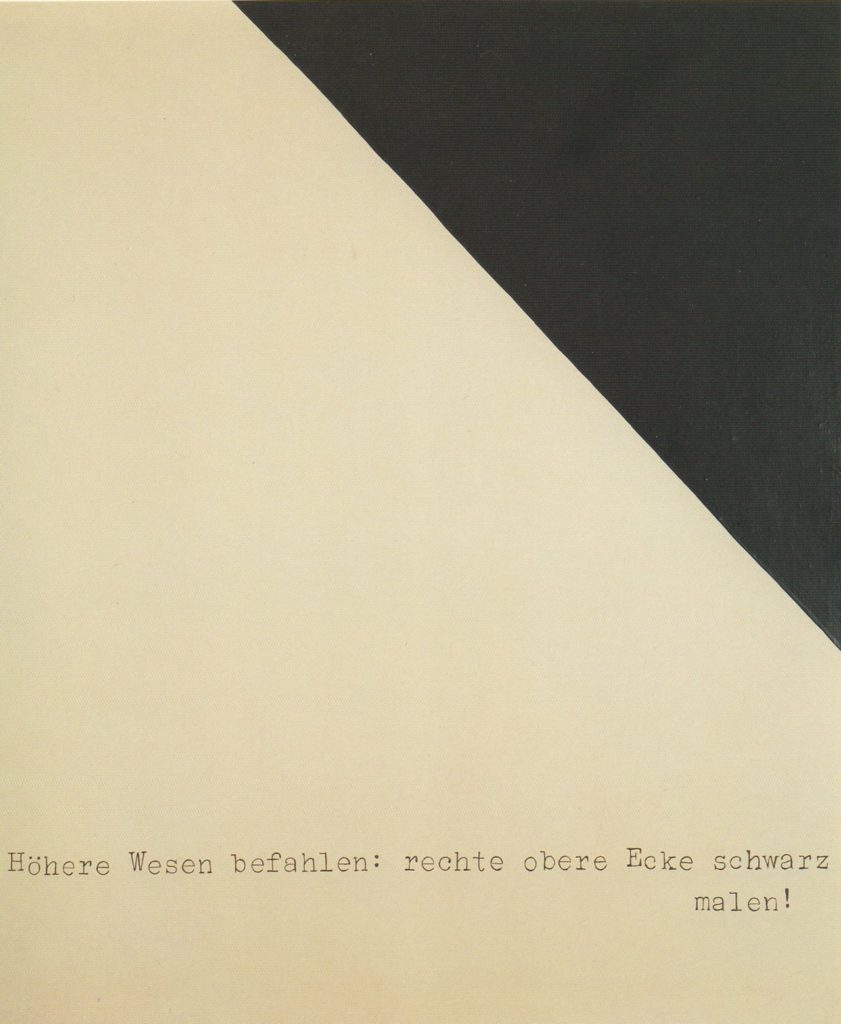

In 1969, German artist Sigmar Polke (13 February 1941 – 10 June 2010) produced a painting titled Higher beings commanded: paint the top right corner black!

The impact of black on white is cataclysmic. The light and dark collide with ringing force. While the piece applies some schoolbook ideas about art (notably the rule of thirds), it appears unsettled and unbalanced, with the black and black basically at war. The white could be an icecube, losing itself to heat and chaos (I’m reminded of how icecubes always melt at a slant, even on a flat surface) Or maybe it’s the reverse: the black is a body of water freezing solid, losing ground to ice, becoming imprisoned in covalent bonds.

The text underneath reads like an excuse. I’m not responsible for this disaster. I was just following orders. This is the infamous Nuremberg defense, so-called because it’s what the Nazi death camp guards said at their trials.

Sigmar Polke was an interesting and diverse artist, who worked in and incorporated stylistic influence from many schools and traditions. He painted with arsenic, meteor dust, smoke, uranium rays, lavender, cinnabar and a purple pigment from the mucous excreted by snails. Higher beings commanded: paint the top right corner black! is actually part of a sequence of similar paintings, including geometric shapes, birds, and more. Many of them are striking works. All were commanded into existence by mysterious “higher beings”, and all share the same exculpatory denial: It is not me.

What were these higher beings?

That’s the thing: there weren’t any. Artists often describe their creative impulses as something external – a muse, or an inspiration – and sometimes they almost attribute conscious agency to these things. They’re like possessing demons.

But in reality, everything an artist does comes from the artist (minus aleatory methods like those of the Oulipo school, or the Oblique Strategies, use of which is itself a choice). There aren’t any outside forces controlling: or, if they are, they interact with your brain in a way that’s distinctly personal to you.

JK Rowling claims that the character of Harry Potter just fell into her head. It may have felt that way to her, but it’s not true. Harry Potter didn’t fall from anywhere. He was invented by JK Rowling. If she hadn’t existed, Harry Potter wouldn’t have fallen into another woman’s head. He would have never existed at all. She is his mother.

Sometimes, this comes off as a way of ducking responsibility. If the artwork is successful, the artist takes full credit. If not…well, the muse wasn’t speaking that day.

Non-artists play this game, too. The 20th century Indian mathematical prodigy Srinivasa Ramanujan was given to crediting his insights to dreams and visions.

The mathematical genius made substantial contributions to analytical theory of numbers, elliptical functions, continued fractions, and infinite series, and proved more than 3,000 mathematical theorems in his lifetime. Ramanujan stated that the insight for his work came to him in his dreams on many occasions.

Ramanujan said that, throughout his life, he repeatedly dreamed of a Hindu goddess known as Namakkal. She presented him with complex mathematical formulas over and over, which he could then test and verify upon waking. Once such example was the infinite series for Pi:

Describing one of his many insightful math dreams, Ramanujan said:

“While asleep I had an unusual experience. There was a red screen formed by flowing blood as it were. I was observing it. Suddenly a hand began to write on the screen. I became all attention. That hand wrote a number of results in elliptic integrals. They stuck to my mind. As soon as I woke up, I committed them to writing…”

– The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan, 1991, Robert Kanigel, Charles Scribner’s Sons

These were valid results, and I don’t disbelieve Ramanujan. He probably did dream (and intuit) some mathematical things…But suppose they’d proven to be bunk? His defense writes itself. “What do you expect, from a dream?”

Polke is either referencing or mocking the artistic conceit that ideas exist outside artists. Again, this is only true in a weak sense (both Imre Kertész and Elie Wiesel were influenced by the “idea” of the Holocaust, which was external to them), and not in the sense that people aren’t pure, agnostic transmission devices for ideas and impulses.

There are no higher beings who want you to paint the corner black. If you paint the corner black, it’s because you wanted it to be black. Not a demon. Not someone else.

* * *

It finally happens one day.

A shadow crosses the sun. Your tongue is suddenly dry, sticks inside your mouth. The skin papering your body feels alien and wrong, like it doesn’t belong on you. Like it’s too large or too tight or too moist or too dry. The world has stopped moving – you almost hear the thunk of vast gears – and then it starts again. Everything is different.

There is a child on the footpath ahead of you. Shaven head. White judogi uniform. Could be eight or ten. He’s waiting for a bus to take him to class or waiting for a bus to take him home from class but he’ll never wait again. A feeling of power overtakes you, and you grasp a handful of his hair and pull him toward you.

He loses his feet, and you wrap your other arm around him. His thrashing limbs are bony, insectlike, fragile twigs burning in a fire. He does not escape your grasp.

You don’t relax your hold on his head when you drive him face-first into the wall. It happens over and over. Flesh against brick. The thuds became crunches as things start to break inside his face. Teeth at first, then the structure underpinning his face. The human skull has fourteen bones. You pull him back by his hair, and slam him forward. Smash. Fourteen bones. Smash. Fourteen. You imagine them floating freely in his head now, like disassembled puzzle pieces in a blood-filled bag.

You let the child fall away from the wall. There’s a red starburst on the wall where his face was obliterated to ruin. The body lands mercifully face-down, rivers of red sewing stitches through his judogi uniform. His limbs are jittering. Then they don’t.

You stand there, panting, not understanding. The murderous impulse has passed. Your hands no longer conduct vast power. They conduct tremulous shakes and shudders.

The thing in your head is still there, but it’s no longer wound tight with tension. It has discharged its purpose, done what it was meant to do.

You are arrested, tried, and convicted. You tell them about the parasite in your brain, and how it temporarily controlled your actions. This defense goes poorly.

Now you will have a long time to reflect and think. Cast a searchlight inward through your emotional landscape. There is confusion. Shame. Guilt. But at least you know you weren’t to blame. The thing inside your head did it.

But then it does something it has never done before: speak.

“I did nothing, and am nothing. You have imagined me.”

You haven’t.

“The impulse to kill was always with you, and you sublimated it. But now you have something better. An excuse. A reason not to feel the way you feel. But make no mistake, I am and was always a part of you.”

No. You are possessed.”

“Possessed by what? Yourself. Only yourself.”

And then it goes away, leaving a near silence like the rustling of leaves.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.