I can remain silent no longer on an important topic: glam rock isn’t the same as glam metal. Not at all. Anyone who writes “glam rock/metal” (as though these are fuzzy or interrelated concepts) deserves to feel the sting of the lash across their pitiful shoulders.

“Glam rock” is a style that became popular in Great Britain in the early 70s: think Wizzard, T-Rex, and Roxy Music and also think platform boots, scarves, glitter, and flared jeans. The music was 50s-inspired rock and roll with a warm, summery vibe. Glam rock could be pretentiously analyzed as “radical self-manufacture”: its stars were big and cartoony and fake, but not in an “I’m lying to you” way. It was more like “I’m inviting you into a shared dream”. For a few years, the dream was so compelling that audiences accepted the invitation. You could really believe that David Bowie was an alien, Marc Bolan an elf, and Gary Glitter a good bloke with an unimpeachable internet search history.

Glam rock collapsed after three years, replaced by disco and limp-wristed parodies of itself (Mud, Bay City Rollers, Insert Third Example). Bowie salvaged his career from the glitter-strewn rubble; nobody else did. Look at the post-1975 discography of a middle-of-the-pack glam band you’ll see five or six flop albums in a row (with titles like Remember Us? and We’re Back! and Will This Work? and Our Manager Made Us Hire a Bagpipe Player), followed by a break up, followed by a 2001 nostalgia concert featuring two original members, followed by the end.

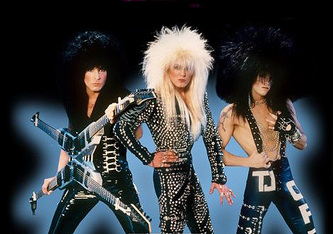

That’s glam rock. Glam metal (also known as hair metal) is very different: a variant of NWOBHM that became popular in Los Angeles in the mid-to-late 80s. Famous bands include Motley Crue, Poison, and so forth. Like glam rock it had outrageous fashion sense, but unlike glam rock it was always the same fashion sense. Bolan didn’t look like Bowie who didn’t look like Brian Ferry, but all glam metal bands dressed the same.

Glam metal was ugly, cynical, and had no soul. Track one would be about fisting a hooker’s ass. Track 2 would be an overwrought ballad about the power of love. It was plastic music, totally disingenuous and shameless about it. It snorted rails of coke off the bottom of the barrel. Tucker Max once said there are “beer and girls” people (those who party to have fun) and “coke and strippers” people (those who party as an act of nihilistic self-destruction). Glam metal was the soundtrack for the letter. The music wasn’t feel-good, it was feel-dead, and often become-dead: Motley Crue’s “Kickstart My Heart” is about Nikki Sixx being resuscitated after going into drug-induced cardiac arrest. Five years earlier, his singer had killed a man in an alcohol-induced car accident. Were you in an 80s glam metal band? I’m sorry that your music career is over, but at least you now have a tear-jerker biography about overcoming addiction to sell to a major publisher.

So why do I bring all this up in a review of a half-forgotten Slade album? Because they’re notable as one of the few bands that played both styles.

They achieved fame in the 70s as part of the glam rock movement: they had six UK number ones. I don’t know why they’re called Slade. Like many glam bands they had a gimmick: they spelled the names of their songs wrong. “Mama Weer All Crazee Now”, “Skweeze Me, Pleeze Me”…I used to think there was a sharp line between artistic affect and crippling dyslexia, but Slade proves that it’s all just gray.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. Slade had the profound misfortune of having “Merry Xmas Everybody” as their biggest chart success. A Christmas song is the worst kind of hit you can have: it means you become pigeonholed as a naff novelty band. It also means the world forgets you exist for 51 weeks out of the year.

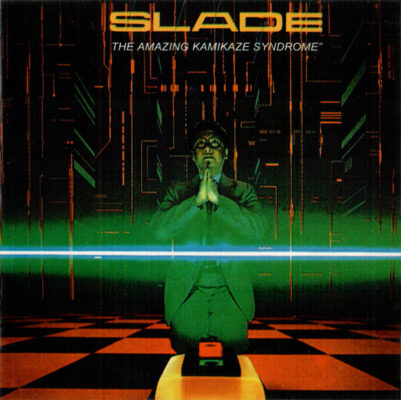

After “Merry Xmas Everybody”, glam rock became unpopular and Slade’s number ones (and soon twos, etc) stopped coming. But in 1983 they managed a minor comeback with The Amazing Kamikaze Syndrome, which broke them in America with a harder, metal-tinged sound.

It’s a loud, hard-rocking and sleazy record. The guitars are like a brick wall and the vocals are like diamond chainsaw tearing through that wall: I don’t know how Noddy Holder’s voice survived so many years of abuse, but science is still asking that question of Nikki Sixx’s heart. “Run Runaway” is a great song, with Jim Lea somehow making an electric fiddle work in a pop context. “Slam the Hammer Down” could almost be a Chuck Berry song, although 80s technology turns it into a massive steroid-pumped gorilla of a track, almost scary to listen to. You feel as if you could get crushed by it.

When the rock-all-the-time approach gets old, you get the eight-minute-plus “Ready to Explode”, which is a weird metal epic combining Queen, Meat Loaf, The Cars, and Iron Maiden. The band pulls influences from just about anywhere, but surprisingly they make most of them work. “My Oh My” is a power ballad with drums so reverb-drenched they might have been recorded from the bottom of the Grand Canyon. It’s like a parody of what music sounded like in the 80s, but it flows nicely and is quite memorable.

“(And Now the Waltz) C’est La Vie” was an odd choice for a single – a Broadway-style ballad with drums that never seem to land where you’d expect. The rest of the album finds the band taking no risks and playing to their strengths, delivering guitar-driven songs with keyboards adding a little color.

Slade wasn’t able to sustain this level of success. Soon they went back being a nostalgia band, and while this isn’t the worst kind of death, it’s a death regardless. Their biggest impact in the 80s might have been the fact that Quiet Riot covered one of their hits. It’s good that they managed this little comeback, but (with typical Slade) bad luck glam metal imploded beneath them just as suddenly as glam rock had. It’s like being aboard a sinking ship and getting rescued by the RMS Titanic.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.