The abduction scene is fantastic; six minutes of such sustained, unrelenting horror that it almost melts the lens. It might have been better to not show so much of the aliens (they look like Baby Groot), but I’ve never seen such a good evocation of how a nightmare feels from the inside. Shadows: screams; reality slipstreaming away like oil; visceral helplessness. I felt like a mouse dying in a cat’s mouth.

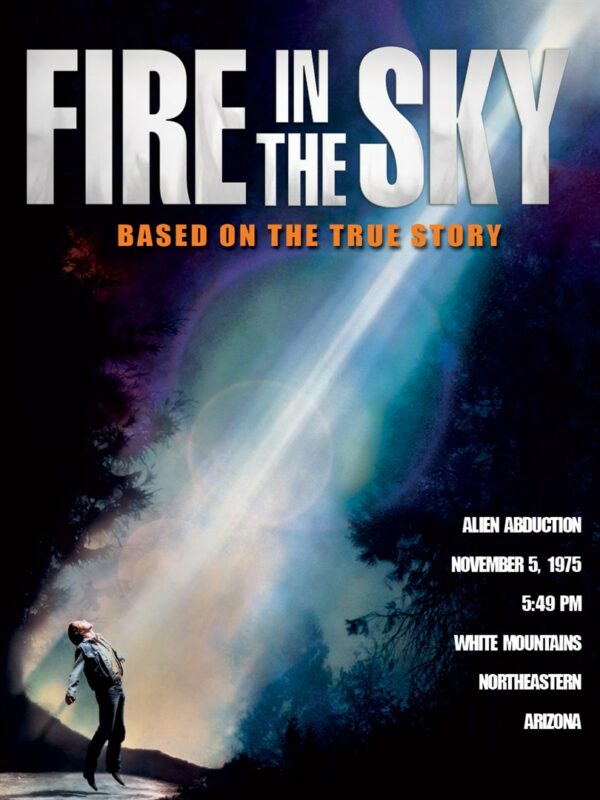

It’s good that Fire in the Sky has that scene, because the rest of the movie isn’t worth a tinker’s damn.

It’s a poor man’s Twin Peaks (Twin Molehills?) about lumberjacks who witness a UFO. The narrative focuses on their emotional journeys as they unpack this experience. Will they come to terms with what happened? Will the townsfolk believe them? Will Flannel Guy #1 mend his feud with Flannel Guy #2? And so on.

On any reasonable scale of importance, “alien visitation” scores a 9.7 out of 10, and “personal dramas of a small-town yokel” scores a 1 or a 2 (unless the small town yokel is you, in which case you might bump it up to a 3). These characters are not interesting and almost cannot be interesting next to the movie’s inciting event. We’ve seen aliens. We do not care about anything except the aliens. Can we talk to them? Reason with them? What do these fey goblins from beyond the void want? Maybe the movie’s point is that there are no answers: that things just fizzle away inconclusively. If so, it fails to fill that silence with anything compelling. It delivers a flat and unengaging soap opera.

The script is wrong, and I wouldn’t know how to fix it. It has one interesting event, which happens at the start, and most of what follows is setup for a joke whose punchline we’ve already heard. This repeatedly causes problems. For example, the movie expects us (the audience) to care whether the lumberjacks pass or fail a lie detector test. But we already know they’re telling the truth (we saw the spaceship!), and thus there’s no tension to the scene. It’s as dead as a dynamited fish.

One of my favorite horror books is Picnic at Hanging Rock, which tries something similar. A mystery at the start goes unresolved, until a town almost shreds itself apart on the axle of that question. You should read it. It’s one of the classics that lives up to the hpye. Hanging Rock was able to blend form and content in a compelling way. The town in that story seemed to be collapse into weird cultlike denialism that was as creepy as the disappearance itself. You’re almost convinced that certain people know what happened, and want it forgotten. The mix of rage and helpless confusion is palpable, and finally infects the viewer. We share in the town’s disease.

Fire in the Sky, by comparison, is made of standard soap opera ingredients. It tries to tell a small, personal story, but does so against a speculative backdrop that’s far more interesting. Imagine a man filming a fly, with a nuclear bomb detonating in the background. Why would you zoom in closer on the fly? The film produces frustration, then momentary horror, then frustration.

It’s based on a true story. I wish I could send this movie back to my 12 year old self. He would have loved it.

I was obsessed with UFOs and alien visitations. I read every book I could, and could recite the “classic” abduction stories (Barney and Betty Hill, Allagash, Strieber, Vilas-Boas) chapter and verse. I’m surprised I didn’t remember the Walton account (which forms the inspiration for this film), but I’m sure I once knew of it. I used to stare up at the sky, and hope to see fires of my own.

Then I grew up, and did as the Bible commands: put childish things away.

Questions are an addictive drug. Once you start asking them, it’s hard to stop. Why do descriptions of aliens always mirror contemporary Earth technology and interests? In the Middle Ages, UFO sightings were of crosses or glowing balls. In the early 20th century, they looked like airships. Now that the “flying saucer” meme is firmly embedded in our cultural neocortex, that’s all they look like. The appearance of the aliens themselves tracks closely with how they’re portrayed in popular culture. Skeptic Martin Kottmeyer acerbically noted that Barney Hill’s abductors (as described by him under hypnosis) bear striking similarities to a monster in the previous week’s The Outer Limits.

And is it likely that an alien race would be bipeds with multi-fingered hands, two eyes, one nose, et cetera? Is it likely that we would be able to breathe their air, and they ours? How could a race of aliens clever enough to avoid detection by the combined firepower of NASA, SETI, and 12 year old Australian boys with binoculars be so clumsy as to be seen by Walton? Where does the invasive “probing” trope come from, if not our horrors of animal vivisection? Wouldn’t they be able to learn about our anatomy through radiographic imagery? And so on.

I still regard UFO stories as interesting (they’re too common and culturally universal to ignore), but they are probably a psychological artifact—the call is coming from inside the house. Aliens might exist somewhere, but barring a revolution in physics, I expect their civilization (or ours) to die in the shadows of space before we ever encounter each other. The only alien intelligences we are in contact with are the homebrew ones at OpenAI and DeepMind. And yet…

“Oh, those eyes. They’re there in my brain (…) I was told to close my eyes because I saw two eyes coming close to mine, and I felt like the eyes had pushed into my eyes (…) All I see are these eyes…”—testimony of Barney Hill

…The best UFO stories—and notice that I don’t specify whether they’re true—have a horror pulsing under the skin that leaves me enthralled. They’re signposts pointing to a very dark place: either out into the chill of space, or inside, into the wilderness of our minds. No matter what you believe, we cannot escape the horror of not being alone. “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door.”

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.