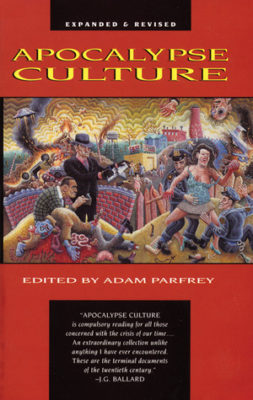

Apocalypse Culture is a 1987 survey of “fringe” culture. It’s not a book, it’s a pointing finger. “Hey, were you aware of this satanic cult? This serial killer? This illegal medical procedure?”

But we have the internet now, and the 2edgy4u info junkies in Parfrey’s target audience just answered “Yes, yes, and yes.” And even if you didn’t know these things, a print book isn’t a good way to learn about them. Books are good but also bad: you can’t drill deeper into an interesting topic by clicking a hyperlink, can’t look up the definition of an unfamiliar word, can’t view a comment challenging the author’s theory and positing a different one, etc. Dives into the tangled parts of the world are better done online, and publications like Apocalypse Culture (including Russ Kick’s Psychotropia, V Vale’s Re:Search, David Kerekes’ Killing for Culture, Jim Goad’s Gigantic Book of Sex, etc ad nauseam) are obsolete, no longer worth buying, reading, or writing.

Or, if you buy and read them, it won’t be for their original purpose. They’re interesting as historical documents: the late 80s and 90s are occupy a fuzzy position in society’s light cone: too recent to be historiographed like the 1960s, too old to be reliably archived by the internet. There’s a lot about the specific weltanschauung of 1995 (for example) that is largely forgotten except by the people who were there.

Millenium psychosis, for example. Kids often find it hard to believe that a lot of people thought the world was going to end in the year 2000. They were counting down the days until 1/1/2000, when computers would explode, the banking system would crash, and the human race would be dragged back to the Middle Ages. I had a friend ask me if I owned a pet, I said yes (a cat), and he advised me to emotionally prepare myself for the day I killed and cooked my pet for food. Twenty five winters ago.

A lot of this “not long…not long…” mentality is found in Apocalypse Culture, – more accurately, it saturates the text, like a layer of salt or spice. Every aberrant sex act and laceration is adduced to the fact that the end is coming, and we deserve it. JG Ballard describes the book as “terminal documents” for the 20th century. That sort of fits. The world didn’t end in 2000, but if it had, this book’s contents could be filed under Cause of Death.

In The Unrepentant Necrophile: we meet Karen Greenlee, “an American criminal who was convicted of stealing a hearse and having sex with the corpse it contained”. She explains the appeal of necrophilia (without success, it must be said), as well as the mechanics – for example, how does a woman perform a meaningful sex act with a corpse (answer: with a strong imagination). Necrophilia isn’t what it was in the 70s. Once, one of Karen’s signature moves was straddling a corpse and making it purge blood from its mouth into her own. In the age of HIV, it’s no longer safe to do this.

There’s a rare pre-arrest interview with Peter Sotos, who offers some typically sensitive thoughts on the gender issue (“Homos are a bit more attractive than women when they’re on top but disgusting when they’re on bottom. That sort of submissiveness stinks of femaleness.”)

Many essays assume you’re already ass-deep inside their particular intellectual rabbit hole, so to speak, and are inaccessible to newcomers. The Cosmic Pulse of Life is a discussion of psychoanalyst UFO researcher Wilhelm Reich’s work, and slings around terms like “orgone energy operation” and “kreiselwelle functions” without the slightest clue that the reader might need a guiding hand. The article gets silly at the end, with Reich zapping UFOs hovering over his lab with orgone-powered laser weapons. It might have been written as a joke.

There’s a bit of 1488, if you catch my meaning. Another reason books like Apocalypse Culture are out of vogue is that even fans of edgy media don’t really want to platform Nazis. Parfrey (who, under the Amok Press name, published a novel by Goebbels) didn’t give a fuck. One of the longest pieces in the book is his surprisingly well-read histography of eugenics, which he concludes is a good idea that should be practiced again. He paid the social price: a lot of contemporary discussion of (half-Jewish) Parfrey and his works consists of rebarbative arguments about whether he was a Nazi or not.

There are some unreadable things by Hakim Bey and Anton Szandor LaVey, who probably got in the book because of their names. Famous names are dangerous: they tend to open doors that should have stayed shut. The Invisible War ranks as the stupidest thing in the book. It reads like it was written by your 80 year old hippie aunt who just got into QAnon. I’m convinced Parfrey would have published the High Priest of Satan’s grocery list.

Maybe my favorite thing is Every Science is a Mutilated Octopus, by Charles Fort.

Every science is a mutilated octopus. If its tentacles were not clipped to stumps. it would feel its way into disturbing contacts. To a believer. the effect of the contemplation of a science is of being in the presence of the good, the true. and the beautiful. But what he is awed by is mutilation. To our crippled intellects. only the maimed is what we call understandable, because the unclipped ramifies into all other things. According to my aesthetics, what is meant by beautiful is symmetrical deformation.

This is bad writing but an interesting perspective, and one that’s withstood the years better than LaVey’s talk of subsonic earthquakes. Science is dangerous. Not as a side effect, but as a direct product. The more science we do, the more danger we expose ourselves to. Think of the things we’ve gained since Fort died in 1932. Nuclear weapons, defoliants, Biopreparat. The future holds worse. A superintelligent AI with goals misaligned with humanity would conceivably eliminate us with the unthinking inevitability a land-grader crushing an anthill. Science must be mutilated if we’re to survive it. Science with its tentacles intact might be more than just an octopus, it might be Cthulhu.

Books take the wild flux of changing times and freeze a snapshot of it. A lot of the past looks strange now, but was compelling when you were in the midst of it, and Apocalypse Culture brings it all back. And perhaps tomorrow, these alien fears and obsessions might become relevant once again. The universe is the site of a neverending apocalypse, and we’re standing in the middle of it, wondering how everything can be exploding all the time without the sky ever going dark.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.