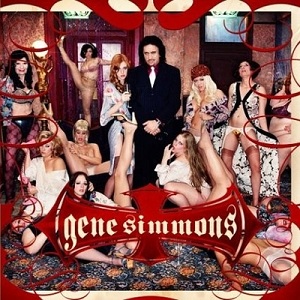

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

The book is called “Submission”, not “Rebellion”. Expected notes of defiance or insurrection aren’t found here. Nobody hides a dagger inside a niqab or hijab. The heart of the matter is this: Michel Houellebecq doesn’t think Western culture is worth saving. His take on an Islamist takeover of France is something like “good, you deserve it.”

The main character is incidental: a middle-aged literature professor who lays pipe in various female students (apparently Houellebecq wasn’t very successful with the fairer sex when he was young. He’s certainly making up for lost time in the pages of his books). Blearily, as if through a panopticon, we see the political stormclouds rattling France. In order to obstruct a right-wing takeover, France’s Socialist party is allying with the Muslim Brotherhood, turning them from a wedge party to an actual force. Soon, Francois sees the future: Islamist Mohammed Ben-Abbes will be president of France.

Scenes of Francois’s daily life are deliberately flat and empty, like slashed tyres. Things like microwaving dinner end up being little manifestos of ennui. Houellebecq hits you hard with pointlessness of it all, and although he almost superglues his tongue inside his cheek (one of the places Francois stays is the site of the Battle of Tours in 732 ad), it’s hard to call this book satire, unless it’s satire with an incredibly broad target: like western civilization or perhaps sentient life as we know it.

The book came out on the 7th of January. On the same day, two Al-Qaeda shooters blessed and culturally enriched eleven magazine publishers in France. For all Houellebecq’s contempt for Islam (“the stupidest religion”, as he says), it’s never dealt with him as it has with Charlie Hebdo, or even Salman Rushdie. Indeed, it’s mostly his fellow westerners that have caused him problems, charging him with hate crimes and forcing him into exile and all the rest of that business.

On one hand, Islam occupies a central role in Submission. On the other hand, it’s hardly in the book at all. French decadence is Houellebecq’s real target. Islam, as he sees it, is just a memetic predator in a world full of memetic predators – it’s the responsibility of guards to stay at their posts and keep the predators out. And France has found her guards asleep at their posts.

After Charlie Hebdo, I assume people rushed out to buy Submission, expecting solidarity and French pride and saber-rattling, and were a little surprised by what they got.

It’s not that Houellebecq’s writing is dark. Lots of writers are dark. The thing is that you never know where you stand with Houellebecq, or are sure of what he’s truly saying. I don’t mean that in an obscurantist postmodern sense. I mean it in the sense of Hitler’s quote “You will never learn what I am thinking. And those who boast most loudly that they know my thought, to such people I lie even more.” Houellebecq’s work is full of crypto-Marxist and crypto-reactionary asides and allusions, like squid ink to conceal his true views. What, finally, is Houellebecq’s stance? That France needs to recover its spine? That’s too easy.

His mind is a black box, and so is this book.. In the end, the only thing I can draw from the soil of Submission is that France can probably no longer with saved. He’s a bit like Martin Amis, who was born in the UK but has permanently relocated to the US. Sometimes you can take the jungle out of the boy.

No Comments »

How many tell-all books about KISS do we need? Here’s everything you need to know: Gene and Paul = high-functioning assholes, Peter and Ace = low-functioning assholes. This dynamic anticipates and explains every twist and turn of the KISS story in the past 40 years.

How many tell-all books about KISS do we need? Here’s everything you need to know: Gene and Paul = high-functioning assholes, Peter and Ace = low-functioning assholes. This dynamic anticipates and explains every twist and turn of the KISS story in the past 40 years.

Drilling a bit deeper, you could say that Peter is deeply insecure and has a Napoleon complex, while Ace was/is a skinsuit piloted by various drug monkeys that doesn’t care about anything much except getting high. You could say Paul is deeply insecure and holds fantasies of being an “icon” (a rock god, a sex symbol, whatever), while Gene Simmons is basically after “fuck you” money. So in a sense, you could draw a dividing line orthogonal to the first one. Peter and Paul’s motives are complex. Gene and Ace motives are simple.

Despite his simplicity, Simmons is the most intriguing part of KISS. The man is so naked and undisguised in his greed that he becomes fascinating, and even a bit likable in a perverse way. It’s as if Donald Trump played rock and roll.

This is the worst album I’ve heard all years. It’s the worst album I’ve heard in several years. It is unmarred by a single listenable cut. It’s not even a failure, it’s just…anti-musical. Like something that was never even intended to be good.

What do you think of bands like the Pretty Reckless? If you’re like me, your answer is “not much”, but I wouldn’t dispute that they’re at least trying to write music that you’ll enjoy. There is no way on earth you’re supposed to enjoy Asshole. It was made by a mind filled with contempt and loathing for his audience, someone who wishes he could just reach into your wallet and take money but is limited by law to the next nearest thing. It’s like having Gene Simmons flip you the bird for 40 minutes.

Horrible performances of horrible songs, that’s what’s on offer here. Gene’s voice is shot, he sounds like a 60 year old man doing karaoke. “Sweet and Dirty Love” and “Weapons of Mass Destruction” sound like what old people think heavy metal is – noise and no hooks. The title track features the couplet “you’ve got a personality / Just like a bucket full of pee”…yes, that’s what we’re working with here. “Carnival of Souls” has an unbelievably terrible chorus.

Then there’s a cover of “Firestarter”, a perplexing choice that is ruined by Gene’s flat “your call is important to us” vocal delivery. You know how they used to joke that Arnold Schwarzenegger has an acting range stretching from A almost to B? Gene Simmons is the same, but remove the “acting” part.

And are you ready for the horrible news? The terrifying “Soylent Green is People” revelation?

These are the album’s good songs.

The rest of this CD is packed with terrifying and near-apocalyptic crap that sounds like adult contemporary/soft RnB music. It’s not hard rock, it’s not even soft rock, it’s basically Boyz 2 Men with a bad singer. I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t. It feels like this must be a false memory implanted by the government. Why would the bassist of KISS release an album where at least 50% of the music sounds like a gentle spanish. Then I hear the gentle Spanish guitars and female backup vocals of “If I Had a Gun”, and I realise the nightmare is made of flesh, not dream matter.

Did you know Gene Simmons has a sex tape? Yes, I’ve seen it. No, he doesn’t look any better in his birthday suit. This album sounds like the kind of thing that could have scored it.

No Comments »

Most of the reporting on this is terrible, sourced from tweets and suchlike. Here’s a good article on what went down, why it was probably inevitable, and what the ramifications are for the Australian music business.

Most of the reporting on this is terrible, sourced from tweets and suchlike. Here’s a good article on what went down, why it was probably inevitable, and what the ramifications are for the Australian music business.

Some observations.

1. Past iterations of Soundwave actually had good lineups, but this one didn’t.

This year, you got to pay $170 to listen to various washed up British hardcore bands, even more washed up American nu metal bands, plus Frenzal Rhomb. They’re a huge draw, I guess…?

AJ Maddah claims on Twitter that he nearly wrangled a RATM reunion, and that would have been something. Like a lot of his management, it seems SW16’s success depended on all the stars aligning.

Look, if only mediocre bands want to play your festival, that’s fine – but you have to adjust the ticket price downwards. SW16’s ticket sales sucked because the bill just wasn’t worth it. Nobody wants to pay $170 to see Disturbed. They are not headliner material for a show of this magnitude.

Going over to Europe, you can see Manowar screw up their own effort at a festival with the same mistake. Magic Circle Festival 2007 cost €10. Everyone and their evil twin attended. Magic Circle Festival 2008 cost €80, but they had a great lineup and a once in a lifetime opportunity to see Manowar play their first six albums back to back (the show lasted over three continuous hours). Magic Circle Festivals 2009 and 2010 had nothing special going for it, no good bands except Manowar…and it cost €75. The value had gone, but the price stayed the same.

There was no Magic Circle Festival 2011.

2. Maddah’s doing the same thing everyone does.

That is, robbing Peter to pay Paul and trying to cover old debts with a slew of fresh debts. This isn’t uncommon in finance. Lots of successful companies work this way. Just keep ballooning upwards on an ever-increasing pile of debt, and you’ll look like you’re a rising star. The trouble is, eventually things contract, and then you’re not able to pay people.

Read the article, especially the part about various contractors and freelancers persuing unpaid debts related to SW and Maddah. These are guys who had gotten burned and were consequently pretty unwilling to extend credit to SW, thus putting a spoke in his wheel. While SW was looking like a success from the outside, the foundation was already crumbling.

And then there’s the unpaid talent. That’s really bad. These bands all talk to each other, you know? It’s hinted between the lines that Maddah had trouble wrangling with acts like Bring Me the Horizon because they knew his habit of writing rubber cheques.

And these were the bands Maddah counted on to recoup the losses of 2014 and 2015, keeping the next stage of the game going.

3. We should put some R&D money into more bands like Compressorhead.

Seriously, no more flakey musicians and drug overdoses and reunions that fall through. Although, like RATM, they seem to be having singer problems.

No Comments »

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.