Most scams are only viable at a small scale. Strangers in Paris might fasten a “friendship bracelet” around a snatched wrist and then demand payment for it, but this trick can’t go beyond a few tourists losing tiny amounts of money. If it becomes too common – with Av des Champs-Élysées flooded with grifters offering bracelets – tourists will get smart and the grift won’t work. There will never be a billion dollar friendship bracelet industry.

There are only about three or four cons that work at scale (thank God). The most prevalent is the bagholder con: borrow money from some people, use their money to inflate your perceived value, borrow a larger amount of money from more people, and then use their money to repay the first.

This scales very well. In fact, it has to scale. The moment there are no new investors – when Paul wants his money back, and no Peter exists to rob – the scheme falls apart.

Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes, MLM schemes, and stock market pump-and-dumps are riffs on this idea. Karl Marx identified capitalism itself as a bagholder con, requiring ever-increasing profits to support itself. Regardless of whether he was right, the con succeeds because it’s reminiscent of how real investment looks and works. “Today, you pay me x. Tomorrow, I pay you x(1+y).” This can be a healthy thing, rewarding risk-takers and people with vision. Done right, it is nothing less than fiduciary time travel, moving money from the future (where it’s useless) to the present (where it’s not).

“This thing will be worth lots of money tomorrow. If I just had enough cash to get it off the ground…”

But in bagholder cons, the thing is worth nothing. It’s a lemon. It will have no value tomorrow, next week, next year; it is pluperfectly worthless except as the life support system for a speculation bubble. Sometimes there is no “thing” at all, just a wind-filled space. Charles Ponzi’s 1920 scheme (which involved the arbitrate of postal coupons) was exposed because it was physically impossible for Ponzi to be doing what he said he was doing: he’d have needed to mail hundreds of millions of coupons, exceeding all legitimate mail in circulation many times over.

The winners in such schemes are typically people who invest early, have the value of their share pumped by gullible “bag holders”, and then pull their cash out before reality reasserts and the price crashes to the floor.

The losers are the people who get in late, or those don’t sell – those who think that the price crash is some moral test the have to pass.

Technically speaking, anyone who invests in anything is a loser. There’s no way around it. Money has gone from your pocket to someone else’s. You might expect to regain it later, but until that happens and you cash out successfully, you have lost 100% of your investment. This is similar to how any money added to a poker pot should be regarded as lost money – until you win, it’s gone. But gambling is universally seen as either a fun game or a harmful addiction, while investment (at final evaluation, gambling with a business degree) is regarded as responsible financial behavior. You’re building the future! Maybe your own. Maybe someone else’s.

It’s psychologically interesting to watch scammed people in action. Some are innocent naifs who were duped into believing a bad investment was a good one (Charles Ponzi’s scheme was a good example). Sometimes, they’re doubly duped: they think they’re getting in on a scam’s ground floor when the actual mark is them (most MLMs fit this pattern). David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con describes how surprisingly few victims of cons actually believe the con was a legitimate way of making money. Instead, most believed they were being invited to rip off someone else.

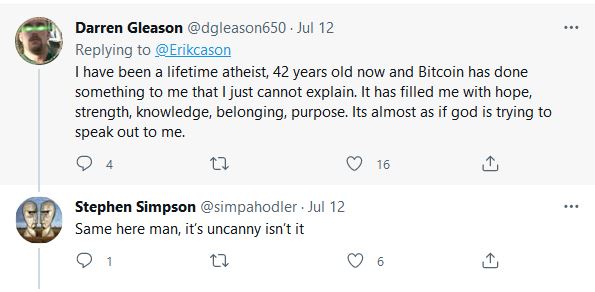

But in either case, the mastermind behind the con does not want anyone to sell. This deflates the bubble, and the bubble’s the only valuable part. So you see conversational patterns cultivated that can only be called cultlike. Unquestioning devotion. Denial of any possible failure. Criticism isn’t tolerated. Questions aren’t asked. Delusional “yeah, we’re all at a party together! WOOO!” styles of rhetoric. There’s a specific way they talk that you don’t see from normal people.

I am suspicious when I see this sort of thing. Hype is a bad signal. It almost looks as if the hype is the entire point, and there’s nothing underneath.

(“hodler” in the second user’s name is affectionate slang for “holding” onto your Bitcoin instead of selling as the price starts to fall.)

In most cases, people with investments have little reason to talk about their investments. If I had a pirate’s treasure map, the last thing I’d do would be to brag about how cool it is to go looking for treasure, or how digging on remote islands will change your life. This can only hurt me, by increasing the odds that the pirate treasure will be found before I get there.

But suppose I didn’t have a pirate’s treasure map. Suppose my income actually came from selling fake maps. Then I might talk about it a lot.

But are cryptocurrencies Ponzi schemes?

The question illustrates a weakness in language. You can say no or yes and be right. Is it literally a Ponzi scheme? No. There are superficial differences. Ponzi schemes are centralized, run by a single criminal, and involve direct transfers of “new money” to pay off old investors. Bitcoin does not have these features.

But if you’re asking “does it share every interesting trait with Ponzi schemes”, I think this is the case.

Every promise of cryptocurrency having real-world utility has thus far failed to materialize. It’s slow, wasteful, expensive, and volatile. Mistakes are permanently written onto an immutable ledger, lost money can’t be recovered, and most solutions (such as “smart contracts”) involve tying the cryptocurrency back to a regulatory body, defeating its purpose.

Various companies adopted Bitcoin in light of the first bubble. Most eventually dropped it, some with frank admissions that it was not suitable for anything except a bubble. Stripe:

Our hope was that Bitcoin could become a universal, decentralized substrate for online transactions and help our customers enable buyers in places that had less credit card penetration or use cases where credit card fees were prohibitive. Over the past year or two, as block size limits have been reached, Bitcoin has evolved to become better-suited to being an asset than being a means of exchange.

Proper investment moves money from the future into the present. Cryptocurrencies do the reverse: move money from the present into the future. Tons of people are still “hodling” as we speak, trying to parlay their savings into a profit in the eternal tomorrow. Because they’ve been told to do so, by people who do not have their interests at heart.

You’ll notice that most cryptocurrency hype focuses, not on things crypto is doing now, but on things that it could do in the future. As David Gerard says, “could” is a misspelling of “doesn’t.”

But this is where we see the main difference between cryptos and Ponzi schemes. They’re bad differences. They

Charles Ponzi was one man. When he ended up in prison. Bitcoin, for example, doesn’t. It’s

Likewise, Ponzi proposed a simple. This could be readily tested against reality, and when it failed, his credibility vanished.

But Bitcoin has no way to fail. One almost thinks it was designed to have no way to fail.

There is no real endpoint Bitcoin is pointed toward. There are several. Evangelists say it will

- Bank the unbanked

- Separate money from the state

- Create a unified world currency

- Protect the economy from crashes

- Enable individuals to transact outside of a legal framework

- etc

Some of these ideas make no sense, and some fight each other. But that’s not the point. This multi-goal argument allows cryptos to continue to seem like a good idea no matter how badly a given prediction fails. It’s a decentralized Ponzi scheme. It takes the bubble and welds nearly unbreakable metal around it, keeping the bagholders from selling.

Bitcoin is propositionally unfalsifiable. No matter how badly a given promise crashes and burns, there’s always going to be something else it could possibly do. You never have to look like an idiot for investing in Bitcoin. You do have to become an idiot, however.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.