Torture. Moral issues aside, does it work?

You have a man in your care, with a fact in his head. Can you torture it out of him? Maybe. But he hates you, because you’re torturing him, so he might tell you the fact in an incomplete or misleading way. And couldn’t you have gotten the fact from him using another method? Consider Knightian uncertainty: you don’t know what you don’t know, and a well-treated prisoner might divulge additional facts that he didn’t have to. A tortured man never will.

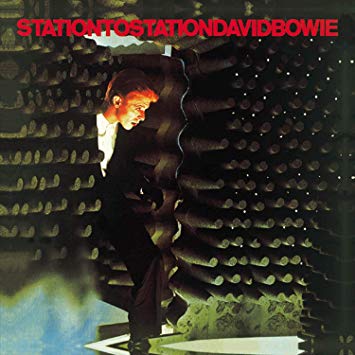

Defenders of torture, of course, have a slam-dunk defense of their art: that it created David Bowie’s Station to Station.

It contains the greatest Bowie song ever (“Station to Station”), the greatest Bowie lyric ever (to be discussed), the greatest Bowie pop song ever (“Golden Years”) and the greatest opening chord on a Bowie song ever (Carlos Alomar’s Am7 on “Wild is the Wind”). I advise listening to this album soon and often. It’s amazing. But do be advised: it was created through torture.

It was created during a horrific period of Bowie’s life, where the drugs begin taking the man. Alone in a mansion in Benedict Canyon, Hollywood, he went insane. It’s all there in the biographies: storing his piss in jars, seeing UFOs, to see his spectral aura, exorcising Satan from his swimming pool, believing that the Rolling Stones were sending him messages in their album covers. Some of these might be myths, or embroideries on the truth. Bowie himself is no help. He says he doesn’t recall making Station to Station at all.

Did he create Station to Station? The album isn’t a pathetic drooling mess of needle injection sites and discarded cocaine twists, as most “druggie” albums. It sounds tight and professional, brightly mixed, with some of his best top melody singing. This is the work of a man at the peak of his power.

The title track is, well, a perfect song. It runs for ten minutes, and you want it to keep going. Train noises are heard, wandering across the stereo field. The train is moving, and we’re not on it. The blurring steel hammer disappears over the horizon, and a loping 2/2 alla breve vamp takes its place. It sounds tight and smouldering on the record, but gigantic live. One of the downsides of the whole Bowie-being-dead business is that he won’t ever play “Station to Station” again. Listeners are free to imagine him in their bedroom, miming to the song while wearing a dress, but somehow it’s not the same for me.

Halfway through, the song erupts, blasting out lyrical and sonic incalescence. “Once there were mountains on mountains!” Cmaj, Dmaj, Emaj, Amaj, Emaj, F#min. The great lyrical moment happen here: “It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine! / I’m thinking that it must be love.” Listen to his difficult, strained delivery, and these two lines crackle with the energy of broken power cables. The world turns beneath him, mountains collapsing to rubble. Just for a moment, David Robert Jones from Brixton is Zeus, hurling thunderbolts. His mind sounds smashed to pieces, reassembled, but somehow stronger and purer than it was before. This signals the final shift in “Station to Station”. The band spins out of control, as if a life-rope’s been cut, and the remaining five minutes are spent in a long vamp built from repeated declamations of “it’s too late”.

Contrary to popular belief, Station to Station has other songs. “Golden Years” is an extremely catchy and well-realised single. The performances aren’t quite as tight as, say, Low (listening to the vocals in isolation reveals that he’s a bit loose with his timing) but the total effect is one of sublime perfection. “TVC15” and “Stay” are similar in tone: jittery, anxious, and funk-driven. “TVC15” is apparently based on a nightmare Iggy Pop had of a TV swallowing his girlfriend. “Stay” is Carlos Alomar earning his paycheck, featuring a jagging main riff with a ninth note thrown in there. The words of the chorus are near incomprehensible word salad: a good evocation of a man who has turned his mind into an MC Escher painting. “Wild is the Wind” ends the album on a plangent note. A jazz ballad, with a wonderful misty and distant feeling.

“He put all of his effort into his art” is a cliche vapid, but it takes on a darker shade: we’re not supposed to put all our effort into one thing. We’re supposed to have lives. We’re supposed to be normal.

I once read a French horror comic (I can’t remember the name) about a race car driver, with a special bond to his vehicle. With his fuel running out, and the great race of his career on the line, the vampiric car sucks his blood out of his veins and burns it, winning the race and hurling a corpse across the finish line. That sums up Station to Station. The stunning artistic heights were achieved at great personal cost to Bowie. It’s a thumbscrew and a rack on a vinyl LP.

Albums cathartic to artists are often dull to listeners, and this is the reverse: another Station to Station might have killed him. After making this album, Bowie fled Los Angeles. As if he himself was the demon in the mansion, and he’d performed his own exorcism.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.