Fire a .22 round and a casing will go plink on the ground. If you pick up this casing, clean it, crimp it, fill it with powder, and seat a new primer and bullet, it will be as good as new.

But when you fire and reload the same casing ten or twenty times, eventually it will not be good as new. The metal will become embrittled, prone to cracking and spalling; the walls will be thin, fluxed outward by temperature and pressure; the primer might no longer sit properly; and it will be liable to misfire. There’s variability both in material – in general, brass casings handle repeated firing better than steel or aluminum ones – and in individual casings. Either way, metallurgy will distort your casing past the point of no return. You can never unfire a bullet.

Gunfire changes bullets. It also changes the men firing them. It’s a common pop culture conceit that war irreversibly transforms men – hauls them across an event horizon to sub- or super-humanity. Veterans return to their families and they’re not the same: they quiver and twitch, they’re prone to explosions of anger. Audy Murphy is the US Army’s greatest war hero, credited with 240 kills. He came back a post-traumatic stress case who slept with a gun under his pistol – a gun he would use to threaten and terrorize his first wife. She’s lucky his kill count isn’t 241.

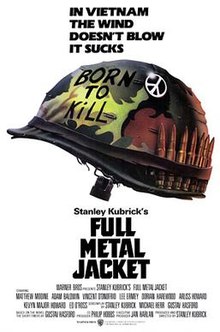

Full Metal Jacket is a latter-day Kubrick film about the above transformation. It depicts the lives of several soldiers (or rather, aspirant soldiers) subjected to the furnace of the Vietnam war. Some crack. Others “survive” in biological terms but jettison parts of their humanity. All seem to have lost something in the end.

It’s fifty percent a great movie. Most films are zero percent a great movie, so that’s not bad. But it’s impossible not to watch it without regret: Full Metal Jacket ends up being much smaller than its shadow. If only it were great all the way through.

Nearly everyone agrees which half of Full Metal Jacket is good. The boot camp scenes at the start – focusing on the relationship between a bullying drill sergeant and a fat, clumsy recruit – are as compelling as anything ever Kubrick put to film. They’re hilarious, cringeworthy, raw, and so thematically complete that when they end, it feels like the movie should also end. It’s actually a surprise when it doesn’t.

R Lee Ermey is fantastic, and carries the movie on his shoulders. He struts up and down lines of terrified recruits like a demonic rooster, reeling off pungently vile insults like stanzas of metered poetry. I’ve heard veterans describe boot camp as “the funniest place you’re not allowed to laugh”, and I think about that when Ermey says stuff like “unorganized, grab-asstic pieces of amphibian shit” and “slimy little Communist shit twinkle-toed cocksuckers“, ready to dump all the shit in the sky upon the first private to crack a smile.

How accurate a portrayal of the boot camp experience is this? I remember a discussion on IMDB’s defunct comments bored – half the vets were saying “This is fantasy” and the rest were saying “This was my experience, exactly.”

Certain things seem right, based on what I’ve heard from friends. Dumping a recruit’s entire kit all over the floor because one little thing isn’t squared away. Punishing an entire class for one recruit’s screw-up. These scenes have a ring of truth. Ermey’s behavior has a cruel kind of logic behind it: he’s weeding out “non-hackers”. In his mind, if you’re going to snap under pressure, you might as well do it at Parris Island, rather than in the field, when the lives of your brothers are on the line.

Vincent D’Onofrio also inhabits his role well: that of a helpless wide-eyed frog getting smashed to pulp by a baseball bat. After weeks of abuse, his eyes start changing, and the drill instructor thinks he’s finally taking instruction. Movie viewers, of course, are aware of dramatic arcs and might guess that something else is coming.

Later, when Joker graduates boot camp and goes to Vietnam, the movie literally loses the plot. None of its events are motivated by anything much. It grinds out some new ideas and characters, but next to D’Onofrio and Ermey’s dynamic they’re not interesting or memorable. I don’t seem to be alone in that assessment. On the film’s IMDB page, the top-voted quotations are overwhelmingly from the early scenes. Down the bottom you’ve got lines spoken in Vietnam by guys I don’t even remember being in the movie.

These scenes are tonally inconsistent. The part where Joker has to write propaganda (“we have a new directive from M.A.F. on this! In the future, in place of “search and destroy,” substitute the phrase “sweep and clear”!) is straight out of Dr Strangelove. Then there’s a moment where a gullible soldier has his wallet stolen by a wacky karate-chopping Vietnamese street gang. Other scenes play their material very straight, without a hint of satire.

A lot has been written about Vietnam, and the way it reflects the final destruction of Clauswitz’s notions of war. No more battle lines. Your enemies dress like civilians. They use women and children, forcing you to make terrible decisions. Your fellow soldiers behave barbarously. Up is down and left is right. You want to escape, but even when you do, the war follows you home, haunting you. What’s it all for?

Kubrick’s film starts out purposeful and ends confused, muddled, and existing just to exist. In this sense it’s the perfect depiction of the Vietnam war.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.