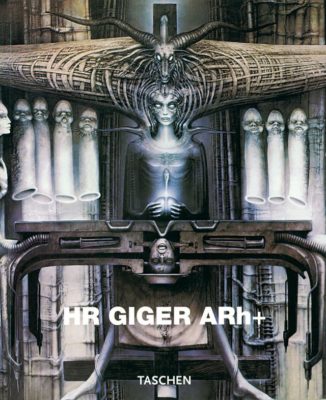

This Taschen artbook explores the work of Hans-Ruedi Giger, who died not long ago. It’s fairly large (23cm*30cm), the print quality is fine, the binding in my copy was falling apart, and Timothy Leary’s foreword is scarier than the actual book. “[Giger] has obviously activated circuits of his brain that govern the unicellular politics within our bodies, our botanical technologies, our aminoacid machines” etc. Yikes.

Why Giger? He was special. Like Hieronymous Bosch, William Blake, and Junji Ito, he saw worlds that nobody else could see. He worked in a lot of mediums but is most famous for his airbrushed “biomechanicals”: totemic, terrifying creatures with dripping teeth, corrugated hides, and electrophosphorescent eyes. They’re an impossible mixture of life and not-life, future and past, sterility and dirt; ancient Egyptian gods built on a Soviet assembly line. There’s little else like them: no artist has ever copied Giger’s signature style with much fidelity. You might say that biomechanicals are more commonly found in reality than in art.

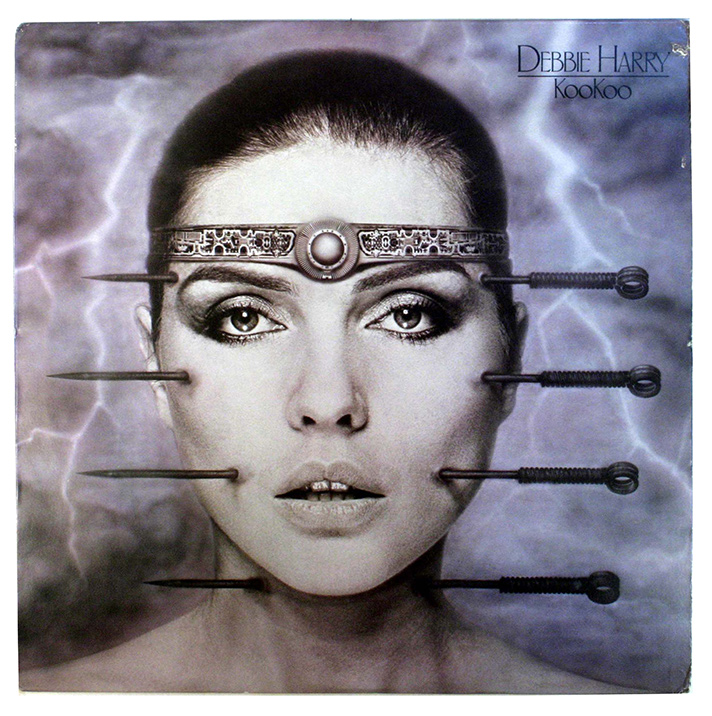

Despite some avant-garde leanings, he was a commercial artist through and through – even after “Giger-mania” took hold in the 70s he wasn’t above decorating heavy metal sleeves, or PC game box art, or guitars, or mic stands, or lager bars. His art showed you unexpected things, and could also be found in unexpected places.

Metal was one of Giger’s favorite subjects. So was flesh, and the ways one can be enhanced or diminished by the other. In the typical Giger image pipes coil and mutate, becoming snakes and phalluses, and glistening shafts and struts pierce necrotic blue-black skin. Giger didn’t predict the future. He grew up in an age of titanium hips, electrical pacemakers, and so on: men have altered their bodies through mechanical means for a long time. Giger’s insight was to tease out the aesthetic power of this union. His creepy-crawly arc-welds of the biologic to the anodic are overwhelming and hit the eye like a bomb. They’re almost too ugly to look at. Or too beautiful. His greatest works actually manage to be both at the same time.

But there’s no sense of gore or mutilation to Giger’s art. He weaves metal through soft tissue and keratin and bone in a way that looks natural, as though evolution rather than surgery produced his creatures. There’s also no motion: Giger’s art has a stillness that’s striking: the “biomechanics” don’t even seem capable of movement. The creature he designed for Ridley Scott’s Alien became a horror movie monster that scampers and leaps around, but there’s none of that in his original artwork, no impression that it might be ready to impale a blood funnel into your chest. It looks petrified in place, a stone god of a stone universe. An advantage of fantasy is that you can create a world that plays to your strengths as an artist, and though Giger never had much talent for evoking movement, he could imagine a place were movement doesn’t happen. His creations are like heavy machines in a factory: bolted into the floor and never moved again. They look perfectly at ease within the environments he creates for them.

The autobiographical text – written by Giger – proves less interesting than the pictures. He doesn’t want to talk about himself, which I submit is a disadvantage when writing an autobiography. He grew up in 1940s Graubünden, lived a childhood so uneventful it’s a miracle he didn’t perish from boredom, worked in advertising, and so on. His father wanted him to become a pharmacist, but he had a dream, maaan. Giger focuses on the dullest details possible, and we never really understand what formed him as an artist. This continues in later passages, where he relates his rise to fame (which reached its peak in 1979, when Alien won him an Oscar for Best Achievement in Visual Effects). Occasionally there are oblique suggestions of personal trouble. “…after the PR commotion and stress”…what stress? “My inner despondency…” What despondency? Giger’s biography fails a basic test: it’s less vivid and informative than reading his own Wikipedia article.

I know someone who attended a Pink Floyd exhibit in Milan – one clearly curated by Roger Waters or someone, because it whitewashed away any controversy, reimagining Pink Floyd as a band of great mates who got on a treat and made awesome music together. The problem (aside from dishonesty) is that the Pink Floyd story is incomprehensible if you don’t talk about the bad stuff – Syd’s mental collapse, Waters’ disillusionment, the destructive infighting. A naif would be left standing underneath a huge sign saying “PINK FLOYD IS BACK!” and wondering “where did they go? And why are there now three people in the band photo instead of four?” Giger’s account of his own life was is a little like that. Things were clearly being left unsaid, which is a shame. I suppose the pictures are the important thing, but they needn’t be the only thing.

The Giger style lives on after him, even though he’s the only one who could really do it. Otherwordly or alien is a common adjective used to describe it, but it’s a specific cold-blooded alien aesthetic. I used to read popular astronomy books which would talk about how moons such as Europa and Enceladus might have liquid oceans, and there would always be the suggestion that we might find fish living there. This is unlikely: life requires a source of free energy, and there’s almost none in such systems. If anything did live, it would be very slow, very conservative of motion. It might communicate and reproduce through radio photons. It would shift fractions of an inch per millenia. If it could think, it would regard motion the way we regard time travel – as an absurd theoretical conceit.

In other words, they might look like HR Giger’s half-frozen monsters. Very cold. Very old. Shunning movement. Giger was the god of the formaldehyde-filled vein, the unbeating stone heart, the liquid nitrogen-cooled brain, and this book cryo-preserves a lot of his unique genius.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.