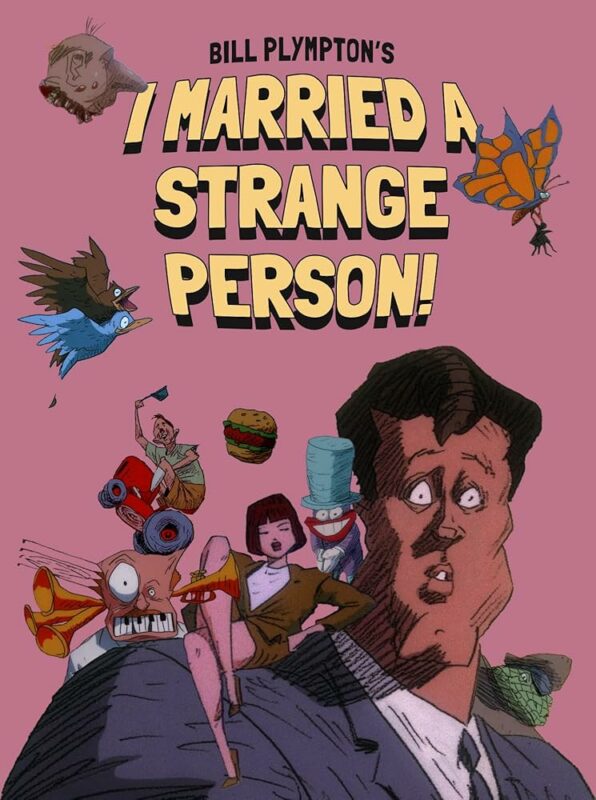

This adult animated film (from 1997, re-released by Deaf Crocodile) left me with a question: where has Bill Plympton been all my life?

Well, drawing, obviously (his illustrations were once in every men’s magazine). A better question: where have *I* been all of *his* life? This rocked from beginning to end, and was the most fun I’ve had with a movie in a long time.

I call it an *animated film* with some reservations—Plympton’s drawings are thrillingly dirty and itch like a hair stuck to the inside of your mouth, but they remain *drawings*. There’s little attention spared for the temporal language of animation (timing and anticipation and so on), and it’s largely filmed on threes and fours—characters don’t flow, they jerk and stutter. These cost-saving measures soon become part of the film’s scrappy, relentless charm. It’s a descendant of those extremely early 1910s cartoons (think *Mutt and Jeff* and *Krazy Kat*) that were basically flipbooks of moving images. Plympton’s art has a visibly constructed quality that I quite like. As noted in the accompanying audio commentary, Bill Plympton would often erase a drawing and then redraw on the same sheet, meaning you sometimes see ghosts and afterimages of erased work in the final shot.*

[1]*I was reminded of Will Vinton claymation—the way he doesn’t seem to care that his clay models have fingerprints and bulges and so on. A lot of labor went into it, and that labor is allowed … Continue reading

But animation is great because of one thing, and it’s a thing the film grasps hard enough to draw blood: *you can create anything*. The film is tailor-made to exploit this idea: a newlywed man named Grant is zapped by a radio signal and gains the power to control reality, which has terrible consequences for those around him—particularly his new wife, Keri. Grant’s new “superpower” (I guess) is that all his intrusive thoughts manifest as literal reality. The human brain is an association machine, a demon monkey flinging shit at the wall, and we’ve all had our moments of “thank *fuck* nobody can see the thought I just had.”

Grant has no fucks to thank. Whenever he imagines something—no matter how obscene or bizarre—it just *exists* out in the open. His wife comments that he has “bedroom eyes”, and his face literally transforms into a bedroom (it makes sense in context…kinda). Her breasts remind him of balloons, so he literally can twist them into balloon animals. Throw in some cute songs c/o longtime collaborator Maureen McElheron, and a recurrent steel guitar jag, and that’s the movie. Grant’s innermost fantasies just burst out of him all the time like animals escaping a zoo, leading to all sorts of perversely amusing gags and adventures. There’s a stock B-movie plot about a totalitarian corporation seeking to control Grant’s powers (this is pretty ordinary stuff, and not the movie’s strongest point), but the movie really is just joke after joke after joke.

It gallops at breakneck pace, six laps ahead of the viewer. I kept having to pause because it was overstimulating the living crap out of me. The film is a triumph of quantity as well as quality: so relentless in its attack that it wears you down and then wins you over. Every scene is stuffed with throwaway gags, jags, riffs, and surrealist fancies, all working by the principle Tex Avery perfected in the fifties: just machinegun the audience to death with *every joke idea you’ve got*—even if only 50% of your material lands, you’ve turned the viewer into Swiss cheese. And Plympton can afford to be far more transgressive and foul than Termite Terrace was ever allowed to be. Things that are (mostly) implied in Avery’s work just get drawn outright here.

It’s not just a lunchroom food fight. The film *does* have stuff to say, if you’re in the mood to trowel through penises, feces, and viscera. Like Grant himself, it has hidden depths.

Grant is depicted as a boring square. (Almost literally, his silhouette is a rectangle with a head sticking out.) He is an accountant, vilified since the days of Monty Python and Arthur Pewtie as the most criminally boring profession to exist. He delays his uxorious duties because of work. Is the most boring person you know just a lunatic who’s good at hiding?

This seems like commentary on the animation trade itself, and the odd way it juxtaposes dreams with drudgery. Bill Plympton’s mind is buzzing with some of the wildest and weirdest thoughts ever thunk…but his body is sitting at a desk, pushing a pencil. He’d look like the world’s most boring man if you couldn’t see what he was drawing. The dichotomy of “boring life, wild art” is on full display here, both textually and subtextually. Grant prefers stability and order, but probably for the same reason a lunatic asylum does: because its fundamental nature is chaos. It’s disturbing to Grant (and even to us—*I Married A Strange Person!* could have easily been a horror film) that his life and marriage are being wrecked, not by the dreams of a mad god bent on tormenting him, but by himself. The call is coming from inside the house!

The film’s core is the relationship between Grant and Keri, which is both a self-aware sitcom cliche (complete with meddling in-laws) and unlike any marriage I have seen in any film. Throughout, Keri ponders what to make of her husband. While he’s in the hell of being unable to hide himself, Keri is in hell of not knowing who he is. She has married a ghost. A mirage. A shape. Who is this man—simultanouely deathly-dull and a wrecker of worlds?

*I Married A Strange Etc* can be clunky when it attempts political satire, but its commentary on married life feels dead on. We’re all strange people. How do we deal with it? By becoming hidden people. We pretend the suit’s our skin and the mask’s our face. But we can’t hide forever. At a certain point, we have to let the disguise drop, and reveal who we truly are. Or be revealed. That’s the thing: eventually your secrets always come tumbling out.

Put more grotesquely, if you’re a guy who’s into feet, your wife is gonna figure that out real soon. There’s an awkward conversation to have or not have, but either way, she will eventually know. You cannot spend ten-plus hours a day around a person without having some cracks appear in whatever social facade exists around you.

The movie’s gross-out gags provoke comparisons with another (more troubling) titan of 90s animation. I grew up on Ren and Stimpy. It briefly dominated my inner sky like Sirius. After the corporate toy-commercial deadness of 80s cartoons, it seemed real and electric and alive. Inside the show was the spirit of Bob Clampett, Tex Avery, and Frank Tashlin, still alive and (if anything) twisted to be *even more* freakish. I was in love. John Kricfalusi seemed like animation’s own Martin Luther King; his show a burning fire to consume the papist heresies of the 80s.

But when I watched Kricfalusi’s ill-fated 2004 reboot of the show (*Ren & Stimpy “Adult Party Cartoon”* or whatever), I was struck by how *miserable* it felt. Had Kricfalusi artistically fallen apart? Had this nihilism always been there, and was I just now watching with eyes open wide? I don’t know, but it was like I was seeing right through the show and into the bleak, cragged mind of its creator: a man who hates women, hates his parents, hates 95% of classic animation (and all of modern animation), hates his audiences, and fundamentally does not have much to say, except to stew and sulk on his resentments endlessly. His animation was still technically brilliant, but what was he *doing* with his talent? Did I really want to watch old wounds getting picked open forever in a technically magisterial fashion? A massive bomb, *Adult Party Cartoon* was cancelled after six episodes. Even if it hadn’t, I probably wouldn’t have bothered watching the seventh. I was done. Before the “Cans Without Labels” Kickstarter debacle, before unfortunate discoveries re: his personal life, my verdict on John Kricfalusi’s deal was a big fat “thanks, I got it.”

By contrast, there’s a joyous, generous warmth to I Married A Strange Person that I found appealing and even emotionally moving. It welcomes the viewer in, instead of freezing them out. It doesn’t sneer; it smiles. It’s not cynical or mean. It’s anything but nihilistic. I guess there’s *some* piss and spite (we get the Tex Avery end of Warner Bros more than, say, Chuck Jones). The riffs about an unfunny and sexually inadequate comedian feel aimed at someone Plympton knows. The nefarious Smile Corporation can only be Disney. Walt would have loved to have an armored tank division, even if they did occasionally hump each other like heat-ridden dogs.

It might also be a story about masculinity. What is a man? What is the role of a man? An oft-mocked . These are your two choices, you’re a Man Who’s Bad to Women, or a Man Who’s Not Bad to Women. But “not a jerk to women” isn’t an identity any more than “not mushrooms” is a pizza topping. What actually are you?

I think the default male experience is one of *freakiness*. The sort of freakiness that leaves you isolated and lonely: you have things that are integral to your psyche yet cannot ever be seen by those around you.

It’s generally true that men are a sex of outliers and extremes. Scholastically, boys seem more variable than women, producing more high and low achievers, and this tendency toward extremity seems to carry itself into art as well. *I Married A Strange Person* was made by a man, not a woman. (There are stories we might tell to explain male misfits: from evolution’s perspective, it’s simply not as large a crisis for a man to die or fail to reproduce. Male gametes are small, numerous, and disposable.)

Yes, women can be strange and perverse. But I still remember the Reddit post titled “How can I get my boyfriend to stop digging his tunnel?” To be clear, this was not a metaphorical tunnel. A woman was idly wondering why her boyfriend was suddenly spending all his time digging an enormous hole. Even if all gendered identifiers had been stripped from the post, you still would confidently predict that the hole digger would be a man. “Digging a hole in your yard for no reason” is just a particular kind of madness that only men seem to have. And I wonder if her boyfriend, when he speaks to others, mentions that he’s digging a hole? He’d probably love to talk about it. But he’s also aware—afraid—that whoever he tells about it wouldn’t share his love.

The curse of being a woman is that you are constantly being perceived, constantly on display. The curse of being a man is that nobody wants to know who you actually are. The average woman, viewing her boyfriend’s internet search history, would react with disgust. *Ew. Ick.*

Being a man means hiding your true self from women, and wondering how much you can safely show her. It’s a troubling spot to be in. Maybe she fell in love with your mask, which is rotting to pieces on your face, an illusion more unsustainable by the day. Or maybe she *knows* you’re a freak. Maybe she knew all along, and is hoping you’ll whisk her off on all sorts of bizarre adventures. That’s what you hope for, anyway. My own mother and father had the same kind of relationship as Grant and Keri in the film, now that I think of it.

*I Married a Strange Person!* is an amazing achievement. A bath of idiocy and filth that leaves you feeling strangely wise and clean. I expect that no movie like it will be made again in my lifetime.

“My baby’s in there someplace,” – David Bowie, “TVC 15”

References

| ↑1 | *I was reminded of Will Vinton claymation—the way he doesn’t seem to care that his clay models have fingerprints and bulges and so on. A lot of labor went into it, and that labor is allowed to be visible on the screen. “Look at this insanity. I drew it on paper. What’s your excuse?” |

|---|

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.