Only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing.

And when you have reached the mountain top, then you shall begin to climb.

And when the earth shall claim your limbs, then shall you truly dance.

— Kahlil Gibran

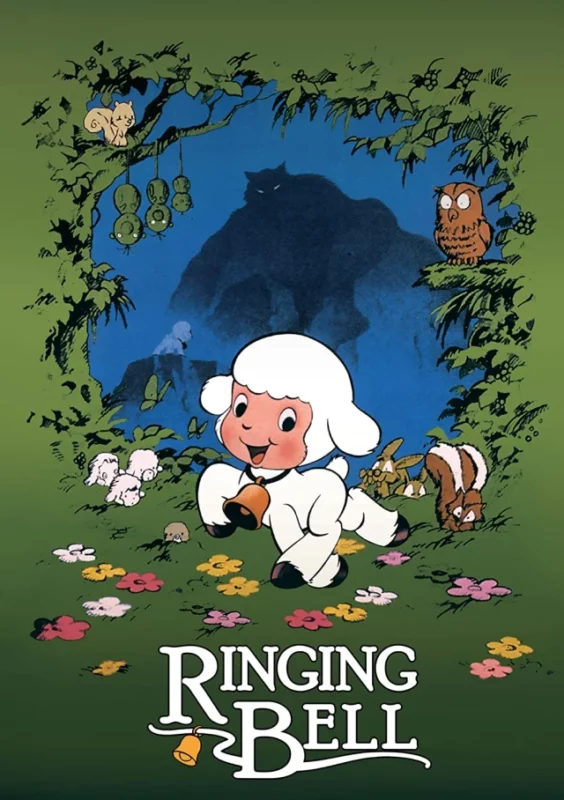

Ringing Bell (released in Japan asチリンの鈴, or Chirin no Suzu) is an anime film from 1978. As we would expect from the studio that created Hello Kitty, it’s like falling down a pit with walls made of severed fingers and writhing snakes. It’s dark. I knew its reputation and it still surprised me with its offhand brutality: certain scenes hit like a loaded body bag dropped from twenty feet. It’s unusually thought-provoking. Usually, “adult anime” means Genocyber or MD Geist: tits and gore plus a childish concept (hey, I watch that stuff). Ringing Bell is different: it uses the vocabulary of childhood nostalgia to tell a mature and sophisticated story about existentialism, injustice, transformation and other topics usually left for incel 19th century philosophers.

Chirin is a lamb. He frolicks in a field of butterflies and small animals. His mother warns him to stay away from a nearby mountain, where a wolf lives.

Disney cliches are piling up fast, and we assume the rest of the movie will be “Chirin disobeys his mother, visits the wolf, suboptimal events occur, and Chirin learns a lesson about the importance of obeying your parents (et cetera)”. But the movie doesn’t go down that road. Chirin is well-behaved lamb, who (aside from one early mistake) obeys his mother. It is emphasized that Chirin does everything right and it doesn’t help in the end.

The wolf invades the farm, because that’s a thing it can do. It slaughters the sheep, because that’s a thing it can do. They die without resisting, because that’s a thing they can’t do. Chirin survives the massacre, but only because his mother leaps upon his body and dies in his stead. In one of the movie’s greatest shots, the wolf lunges, and the (hypothetical) camera zooms in on a scar on its eye. The scar seems to elongate through the black fur, like tear ripped in paper, revealing a slash of orange, which soon darkens to red, and then the red fragments into isolated twists of smoke, as though it wasn’t gore but fire. This is great filmmaking. Director Masami Hata found a way to imply flesh tearing and blood spurting, while displaying no on-screen violence whatsoever.

When Chirin recovers, he sees his mother dead, and the wolf gone. He does not understand. Why does he deserve this? He stands at the cusp of the movie’s central insight: it was not unjust. He is a sheep, and this is what being a sheep means. Millions of lambs have stood in his place. He is not special.

When a movie is about animals, it’s usually for a reason. One of three reasons, actually. The first is that the filmmakers had no choice. Maybe they’re adapting a children’s book written by a laudanum-addicted Victorian pederast called Archibald Featherwyckbottom III and that book has animals. Or they have some suit breathing down their neck, saying “We need to sell eleventy billion plushie dolls this quarter, so make the characters cute animals. We need the furries on our side here, so make them fuckable.”

The second is that it distances the setting from the human world, allowing access to the grand and mythic. It is difficult to tell a yearning, primal story about a character that has to pay rent and file TPS reports. Civilization is an anchor slung around your neck: it keeps you stable, but does no favors if you want to fly. A book like Life of Pi or Lord of the Flies has to forcibly extract its character(s) from the human world before the story can begin. An animal tale like Watership Down can simply get on and tell the story.

The third and most important reason is that animals have characterization built-in. Owls are wise. Lions are regal. Sharks are predatory. Dogs are loyal. Cats are devious, solitary, and sour. Foxes are devious, solitary, and cheerful. Eagles are libertarians. Hamsters are alt-right shitpoasters. Goldfish are effete limousine-liberal crypto-Kautskyites whose commitment to The Struggle is frankly more show than substance. We all know these tropes, and when there’s an animal in a movie, we understand its character before it even says or does anything.

With that in mind, what is the identity of a sheep?

Passivity. As a sheep, you are an object. You get herded around by slow but smart apes and fast but less-smart canines. You graze stupidly and endlessly, mulching grass through four successive stomachs before excreting it into pellets so uselessly precise they look like they came from an injection mold. Even your shit looks domesticated. Such is your life, a hollow tube that grass flows through, until the day the shepherd separates you from the flock, a high-velocity slug engraves death into your skull and the world spins on without you. Nobody asks your permission. Things are done to you, and done to you, and then finally you are done.

(I actually own sheep, and they’re not as domesticated as their rep suggests. They can be very stubborn and aggressive, particularly in breeding season. Males will headbutt you hard enough to leave bruises through thick jackets. I’m sure a nonzero number of people get killed by sheep each year.)

Being a sheep places Chirin in a role of servitude. If he was a man, he would be a helot in 500BC Sparta, a black person in 19th century Louisiana, or a contemporary person who doesn’t find Jacqueline Novak’s stand-up very funny. He is an oppressed minority, living in a cruel and gray world that hates him, and his life is a living hell. He makes an audacious decision: I will not be a sheep any longer. But does that even make sense? A sheep is defined by not having a choice. You can’t choose not to be a sheep, any more than a tongueless man can talk or a legless man walk. (Conspiracists deride normies as “sheeple”…but if we’re truly sheep, we have no choice but to be fooled by the conspiracy. It’s pointless to even complain about. )

So if you could decide to not be a sheep…wouldn’t that mean you never were a sheep to begin with? And thus your mother’s death was a cosmic injustice, and thus his desire to become a wolf is also unjustified? It seems paradoxical. There is comfort in believing the world is neutral of morality, and a different sort of comfort in believing in right or wrong, but you have to pick a lane. However paradoxical the desire, Chirin decides to stop being a sheep.

He tracks the wolf down, and demands that the wolf fight him. The wolf ignores him: denying him even the respect of an enemy. But then Chirin starts demanding that the wolf teach him wolfish ways. The wolf responds with mockery, yet curiously, he does not kill Chirin. It might be that he’s already begun testing Chirin (if you’re truly a wolf, you’ll not be deterred by “you can’t do it”)

Chirin stays by the wolf’s side, and learns the way of the fang and claw. They go on adventures together. The movie drags a bit here, falling into master-and-apprentice martial arts cliches. There’s a cheesy reprise of the theme song, with goofy rock guitar licks dubbed over the top. Ringing Bell can be a somewhat “broad” movie at times. Particularly the music, which lyrically emphasises things we can already see on screen in a very heavyhanded and obvious way.

But then we arrive at the final act, where a movie that has been fairly fascinating becomes utterly engrossing. Chirin is given a choice by the wolf. It’s a brutal all-or-nothing decision, not just for his life, but for his soul. His reaction and what happens next is psychologically complex and fascinating.

Otherwise, it’s just a fairly well-made short film from 1978. The production studio, Sanrio, modeled itself after Disney. Except where Disney was an animation studio that branched out into merchandizing, Sanrio was a merchandizing company that branched out into animation. “Sanrio” is apparently meant to be a portmanteau of “San” (as in “San Francisco”) and “Rio” (as in “Rio Grande”), thus making the company’s name “Saint River”. Truly, they are the Sleve McDichael of the corporate world. Their artistic ouevre could be described as “diet Madhouse”, telling surprisingly deep and complicated (and weird) stories within the conventions of 70s anime. I assumed director Masami Hata later worked at Madhouse, but that seems to not be the case. He did later work on Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland. But every animator in history worked on that movie.

In many ways, Ringing Bell is a product of its time. The art style is very “70s anime”. Characters are designed with circles, where modern anime prefers triangles. There is a tragic dearth of sparkling magical schoolgirls and panty shots and oppai moments. A modern viewer would regard this as a relic of another age.

It is heavily influenced by Disney films—and both subverts those influences and plays them straight. Bambi is an obvious influence—it almost watches like a parody of that movie. The changing of the seasons, the death of a parent, the design of the adult Chirin. The marketing on the poster tries to play up this angle still further, prominently featuring furry critters and an owl who I don’t think gets one line of dialog in the actual movie.

But there’s also a Japanese character to the film which is deeply felt. The arrival of the wolf is an apocalypse, like a bomb falling on the sheep. We see it tearing them apart via silhouettes on the wall, which made me think of the permanent shadows of Hiroshima. It’s based on an anti-war manga. I was reminded of writer Kenzaburo Oe’s realization that the Showa emperor was in fact a mortal man. What better metaphor for a mother dying than that?

The truth is a gift, even when it hurts to hold. Chirin is granted a glimpse of the true reality of the world, one that most folks never get until they’re too old to change. He wishes he could return to the safety of his old life, but there never was any safety. He just had his eyes closed, and now they’re wide open. He lives in a world without justice and fairness. It has sheep and it has wolves. And it has Chirin, who is a sheep and a wolf.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.