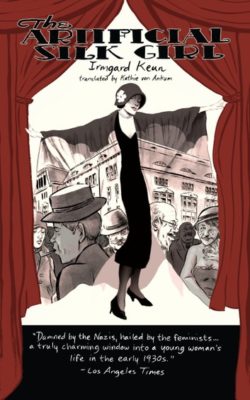

In this 1933 novel, a young woman called Doris gets laid. Too bad that’s only half the sentence, and the second half is “off from work”.

Wearing a stolen fur coat, she journeys to Berlin, intending to make it big as a Glanz – a film star.

“I want to become a star. I want to be at the top. With a white car and bubble bath that smells of perfume, and everything just like in Paris. And people have a great deal of respect for me because I’m glamorous.”

Her plans fail, and she ends up increasingly far from the high life, working as a maid, a pickpocket, and eventually a “girlfriend experience” (to use a modern euphemism). She’s following her dreams, but they’re leading her backwards: like a riptide where swimming harder means drowning faster. All she has is the fur coat, reminding her of the possibility of dreams. But the coat doesn’t belong to her. It’s someone else’s.

Keun writes a character who is stupid and smart at the same time: given to psychological monologues worthy of a tenured psychiatrist while completely unaware of how and when she’s being manipulated by others – men, institutions, and society. Being an actor is hard. You need to be focused, hard-working, very, very lucky, and at the end of the day you either have “it” or you don’t. Before coronavirus hit, Hollywood and West LA were stacked tens of thousands deep with aspiring actors, bussing tables and mowing lawns and firing out headshots like despairing messages in bottles. They won’t all succeed. Supply outstrips demand a hundredfold. “Why does New York have lots of garbage and Los Angeles have lots of actors? Because New York got to pick first.”

The Artificial Silk Girl is a kind of Grecian tragedy – a narrative that moves on towards an inevitable unhappy conclusion, while having a bitchy, funny air that makes it readable ninety years later. It’s seldom depressing or sad: Doris has a bulldog’s tenacity, and never gets kicked down for long. This, ironically, makes her into her own worst enemy: a more realistic girl would have gone home long ago.

The period setting is as much a character in the book as any of the people. Germany’s Weimar years (1918 to 1933) are often viewed as a kind of modern-day Flood parable: an orgy of decadence preceding disaster. There’s hints of political events unfolding, but Doris is blind to them: she’s trying to hustle rich men and get film roles.

She herself is apolitical, but the author wasn’t. When the NSDAP came to power, books The Artificial Silk Girl became unacceptable, and were burned on massive bonfires. Irmgard Keun (living dangerously, one thinks) actually attempted to sue the Gestapo for loss of income.

But Das Kunstseidene Mädchen is most successful not as a political or feminist polemic, but a cautionary tale of the dangers of following a dream. Sometimes ideas are just bad, and it’s almost better for them to fail immediately than to continue on: just as it’s better for a jet plane engine to break down on the runway than at an altitude of 5,000 feet.

Doris’s momentary successes seem almost cruel, because they perpetuate a fantasy. Just when she’s at the end of everything, a ray of light appears…just enough so that she keeps chasing her dream, and remains impoverished, starving, and wearing stolen clothes.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.