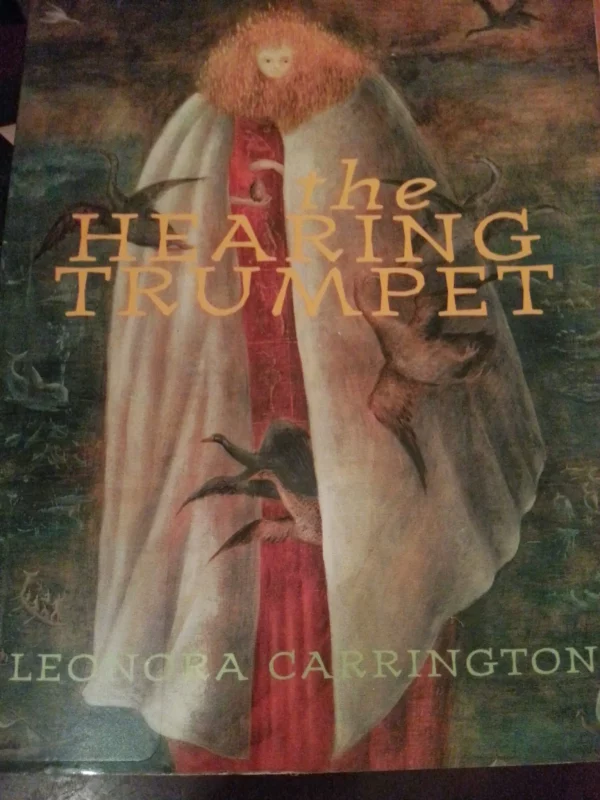

One of surrealism’s last masterpieces, The Hearing Trumpet anchors its story in confinement—an old woman is sent away to an institution—and then sets her free in a metaphorical and literal apocalypse of pagan-inspired imagery. It’s a stealth-story about witchcraft; so stealthy that not even the witch knows she’s inside one.

The beginning’s great fun. 92-year-old Marian Leatherby is gifted a hearing trumpet by her friend Carmella. The first thing she hears through it is her family, plotting against her in the next room.

“The government provides institutions for the aged and infirm,” snapped Muriel. ” She ought to have been put away long ago.”

“We are not in England,” said Galahad. “Institutions here are not fit for human beings.”

“Grandmother, ” said Robert, “can hardly be classified as a human being. She’s a drooling sack of decomposing flesh.”

“Robert,” said Galahad without conviction, “really, Robert.”

“Well I’ve had enough,” said Robert. ” Inviting people here for a normal chat and a drink and in walks the monster of Glamis, gibbering at us in broad daylight until I have to throw her out. Gently of course.”

“Remember Galahad,” added Muriel, “these old people do not have feelings like you or I.”

Marian ends up shunted away to an institution called Lightsome Hall (“very efficiently organized and reasonably inexpensive”), run by the publicity-obsessed Dr Gambit. It’s a queer place, full of nonsensical rules and idiotic people. The food portions are very small. The staff are fond of saying things like “Humility is the fountain of light. Pride is a disease of the soul.”

Clearly, Marian’s family expects her to die there, and to be relieved when it happens.

But Marian has quite a lot of spirit for a “drooling sack of decomposing flesh”. On a wall, she notices a portrait of an 18th century abbess, Dona Rosalinda, Abbess of the Convent of Saint Barbara of Tartarus—an abbess who, long ago, was on a quest to recover the Holy Grail and return it to its proper owner, the goddess Venus. Dona Rosalinda never succeeded, but with the help of some octogenarian inmates, Marian might have better luck.

The book’s halves play with and against each other. Contrasts are set up and explored: Christianity vs Paganism, imprisonment vs liberty, masculinity vs feminity, technology vs primitivism. The book spans a Apollonian/Nietszchiean divide: stultifying rules and de-facto imprisonment, so that Marian’s final transformation (she gets a cauldron, but doesn’t do the expected thing with it!) hits you all the harder.

While reading about neuroscience, I learned about lateral inhibition. It’s where a neuron undergoing an activation spike will inhibit the action potentials of neighbouring neurons. This is perceived as contrast, which makes it easier to notice things. I’d already known from mixing music that the best way to emphasise a given frequency isn’t to make it louder (which creates a “loudness war” scenario where everything is fighting everything for volume) but to cut the frequencies on either side. Waves seem bigger when the sea is flat. The Hearing Trumpet works in the same way.

The book has a lot of depth, if you’re prepared to read between the lines (and above and below and beside them, too). Lightsome House is a parody, not of organized religion, but of mysticism, and Dr Gambit is a pastiche of notorious mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (Gambit’s portentious references to some ill-explained thing called “the Work” give the game away). If you gave me a blind test between Gambit and Gurdjieff quotes I’m not sure I could reliably tell you which was which.

Everything in the book has an absurdist edge. The bizarre design of the institution (buildings are shaped like birthday cakes, shoes, and igloos) could be out of a Roald Dahl or Enid Blyton book. The fact that the Institute is owned by a cereal company, and that people have names like “Galahad” in Mexico, hints that it’s a book with a complicated relationship with reality. The closest comparison to The Hearing Trumpet isn’t surrealist touchstones like Breton or Kafka, but childrens’ literature.

A battle surrealist literature faces is to stop the reader from analyzing every detail as having encoded meaning. This battle is usually a lost one, but in Carrington’s case, the small details really do seem to mean a lot.

Like the hearing trumpet. It “announces” a kind of apocalypse for Marian, just as a trumpet does when blown in the book of Revelation. And the bees (which exist everywhere at the Institution) are an obvious pagan symbol, but they also provide some psychological depth into Gambit (meaning, Gurdjieff). Bees are females, you see. Ones incapable of breeding, ones that he can possess and control, just like the women at the Institute. To be sure, Gurdjieff had a slightly sinister amount of control over his female acolytes. His relationship with them would have produced closer scrutiny had he lived today.

“Gambit is a kind of Sanctified Psychologist,” said Georgina. “The result is Holy Reason, like Freudian table turning . Quite frightful and as phoney as Hell. If one could only get out of this dump he would cease to be important, being the only male around, you know. It is really too crashingly awful all these women. The place creeps with ovaries until one wants to scream. We might as well be living in a bee hive.”

…but that gets twisted, when a colossal queen bee arrives, wearing “a tall iron crown studded with rock crystals, the stars of the underworld.” A symbol of female power.

Despite its lunacy, the story’s a fairly personal one. Carrington’s childhood was marked by rebellion, and institutions of various forms. The staff of a Spanish sanitorium had to repeatedly stop her from climbing onto the roof, to be nearer to the stars. So you see a lot of that coming through in the book. A desire for freedom. The idea that escaping your circumstances might be as simple as locating the right painting on a wall.

Needless to say, Carrington was raised Catholic. I’ve heard it said that if you want your daughter to become a whore, name her “Chastity”, and maybe a strict Catholic upbringing is the perfect one for a nascent surrealist, too. Anais Nin was raised Catholic too, come to think of it…

Like Nin’s Delta of Venus, the world The Hearing Trumpet was written for wasn’t the same one that actually read it. Finished in 1950, it remained unpublished until 1977. It does feel adrift in time. Everything is a little bit quaint and stuffy and old-fashioned. The motif of a hearing trumpet—instead of, say, a cochlear implant—marks it as a book out of its time. And all kinds of little details are “off”, not because of any surrealist intent, but simply because the world had moved on.

Some fifty or sixty years ago I bought a practical tin trunk in the Jewish quarter in New York.

“Fifty or sixty years” before 1950 was the late 19th century. Only a few tens of thousands of Jews lived in New York back then, mostly in the Lower East Side. Obviously, the timeline doesn’t make sense when moved to 1974. There wasn’t a “Jewish quarter” in 1920s New York: well over a million Jews lived there by that point and it was one of the city’s biggest demographics by that time.

Marian Leatherby had to wait nearly a century before her moment came, and I suppose we’re lucky that The Hearing Trumpet only had to wait 25 years. Fascinating, unique book. It established a weird, ossified world of ritual and control, so that the final rapturous explosion has way more effect than it otherwise would. The chains are strong but can still be broken, but that makes it even more impactful when they explode into a thousand shards. Carrington’s book is a restatement of the fundamental point of surrealism. The world is confinement, so find the edge and fall off.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.