I read Stephen King’s Lisey’s Story when I was young. I didn’t get much out of it. The incessant baby-talk (“smucking”, “bad gunky”) felt stickily tiresome, like wading through a saliva-splattered ballpit. The pacing was languid; the plot mushy and oversentimental. It felt like a personal work written for Tabitha Spruce King, with me as an outsider, unwanted and begrudged, sitting at their table and being resented for it.

I read it again now and enjoyed it more. It’s not as inaccessible as I thought. I can better see what King was trying to do. It takes themes he explored at thirty, and lets the (different, dimmer) light of seventy gleam over their cracks and hollows.

The plot basically combines Misery (one of his more successful books) with Rose Madder (one of his less successful). From Misery, we get the idea of an psychopath fan who’s obsessed with a famous writer. The twist here is that the famous writer (Scott Landon) is already dead, and the stalker’s rage and entitlement settles on his bereaved widow, Lisey. That adds an interesting dynamic. In Misery, Paul Sheldon at least had some power. He’s the only one who can write the Misery Chastain romance stories his captor loves, so she’s forced to keep him alive. Lisey Landon, on the other hand, is not her husband. She’s just a person who shared a bed with him. Through the world’s eyes, she’s a person-shaped mirror, a window to her husband. Mirrors cannot create; only reflect. They also cannot die; only be smashed. This heightens Lisey’s victimhood: her husband’s fans and enemies grow obsessed with her, but never actually regard her as a person.

From Rose Madder, he takes the idea of an magickal dreamworld that can be accessed using chintzy artifacts. The otherworldly land of Booya Moon (which Scott introduced Lisey her to while he was alive) is useful. Injuries heal swiftly. It might also be a good place to hide a dead man, or lose an unwanted living one. But it’s ultimately a dangerous place to be. This is because of what lives there: the long boy.

The long boy is one of King’s better inventions; one of his most direct forays (along with “N”) into Lovecraft-style horror.

It is not bound by the same rules as most of the things in Booya Moon. It can reach into the real world somehow (using glass surfaces and mirrors as portals). It has marked Scott as its prey, and has spent a long time searching for him. Occasionally he sees its face in glass, peering around and looking for him.

In the end Scott’s thing had come back for him, anyway—that thing he had sometimes glimpsed in mirrors and waterglasses, the thing with the vast piebald side. The long boy.

Long before we see it ourselves, we hear it, in a second-hand way. Scott knows the sound it makes, and imitates this for Lisey.

Scott says, “Listen, little Lisey. I’ll make how it sounds when it looks around.”

“Scott, no—you have to stop.”

He pays no attention. He draws in another of those screaming breaths, purses his wet red

lips in a tight O, and makes a low, incredibly nasty chuffing noise. It drives a fine spray of

blood up his clenched throat and into the sweltering air.

[..]

“I could . . . call it that way,” he whispers. “It would come. You’d be . . . rid of my . . . everlasting . . . quack.”

She understands that he means it, and for a moment (surely it is the power of his eyes) she

believes it’s true. He will make the sound again, only a little louder, and in some other world

the long boy, that lord of sleepless nights, will turn its unspeakable hungry head.

Later (or earlier, in a flashback), Scott is stranded in Booya Moon, and Lisey travels there to rescue him. Here, she briefly sees the long boy in the unflesh.

“Shhhh, Lisey,” Scott whispers. His lips are so close they tickle the cup of her ear. “For

your life and mine, now you must be still.”

It’s Scott’s long boy. She doesn’t need him to tell her. For years she has sensed its presence

at the back of her life, like something glimpsed in a mirror from the corner of the eye. Or, say,

a nasty secret hidden in the cellar. Now the secret is out. In gaps between the trees to her left,

sliding at what seems like express-train speed, is a great high river of meat. It is mostly

smooth, but in places there are dark spots or craters that might be moles or even, she supposes

(she does not want to suppose and cannot help it) skin cancers. Her mind starts to visualize

some sort of gigantic worm, then freezes. The thing over there behind those trees is no worm,

and whatever it is, it’s sentient, because she can feel it thinking. Its thoughts aren’t human,

aren’t in the least comprehensible, but there is a terrible fascination in their very alienness . . .

“A great high river of meat” is a vivid phrase. Stephen King should consider writing more words. He can be quite good at them.

But she finally sees the long boy’s face—or mouth, at least—near the end.

Then there’s movement from her right, not far from where Dooley is thrashing about and trying to haul himself upward. It is vast movement. For a moment the dark and fearsomely sad thoughts which inhabit her mind grow even sadder and darker; Lisey thinks they will either kill her or drive her insane. Then

they shift in a slightly different direction, and as they do, the thing over there just beyond the

trees also shifts. There’s the complicated sound of breaking foliage, the snapping and tearing

of trees and underbrush. Then, and suddenly, it’s there. Scott’s long boy. And she understands

that once you have seen the long boy, past and future become only dreams. Once you have

seen the long boy, there is only, oh dear Jesus, there is only a single moment of now drawn

out like an agonizing note that never ends.

What she saw was an enormous plated side like cracked snakeskin. It came bulging

through the trees, bending some and snapping others, seeming to pass right through a couple

of the biggest. That was impossible, of course, but the impression never faded. There was no

smell but there was an unpleasant sound, a chuffing, somehow gutty sound, and then its

patchwork head appeared, taller than the trees and blotting out the sky. Lisey saw an eye,

dead yet aware, black as wellwater and as wide as a sinkhole, peering through the foliage. She

saw an opening in the meat of its vast questing blunt head and intuited that the things it took

in through that vast straw of flesh did not precisely die but lived and screamed . . . lived and

screamed . . . lived and screamed.

She herself could not scream. She was incapable of any noise at all. She took two steps

backward, steps that felt weirdly calm to her. The spade, its silver bowl once more dripping

with the blood of an insane man, fell from her fingers and landed on the path. She thought, It

sees me . . . and my life will never truly be mine again. It won’t let it be mine.

For a moment it reared, a shapeless, endless thing with patches of hair growing in random

clumps from its damp and heaving slicks of flesh, its great and dully avid eye upon her. The

dying pink of the day and the waxing silver glow of moonlight lit the rest of what still lay

snakelike in the shrubbery.

At the end of the book, the long boy becomes aware of Lisey Landon. She starts seeing it peering in mirrors, uncoiling muddily at the bottoms of glasses, just as Scott did. (Emphasis mine)

“Looks a little like dried blood,” Mike said, and finished his iced tea. The sun, hazy and hot, ran across the surface of his glass, and for a moment an eye seemed to peer out of it at Lisey. When he set it down, she had to restrain an urge to snatch it and hide it behind the plastic pitcher with the other one. […] They both laughed. Lisey thought hers sounded almost as natural as his. She didn’t look at his glass. She didn’t think about the long boy that was now her long boy. She thought about nothing but the long boy.

Like the madman stalking her throughout the story, perhaps the long boy has marked her as a substitute for her husband. The man I truly want is dead and gone…but in his place, you’ll do.

I wonder where King got the idea for the long boy?

Worms as symbols of corruption and decay are too common to be worth discussing at any length. A mindworm or mindsnake is a more specific image, though.

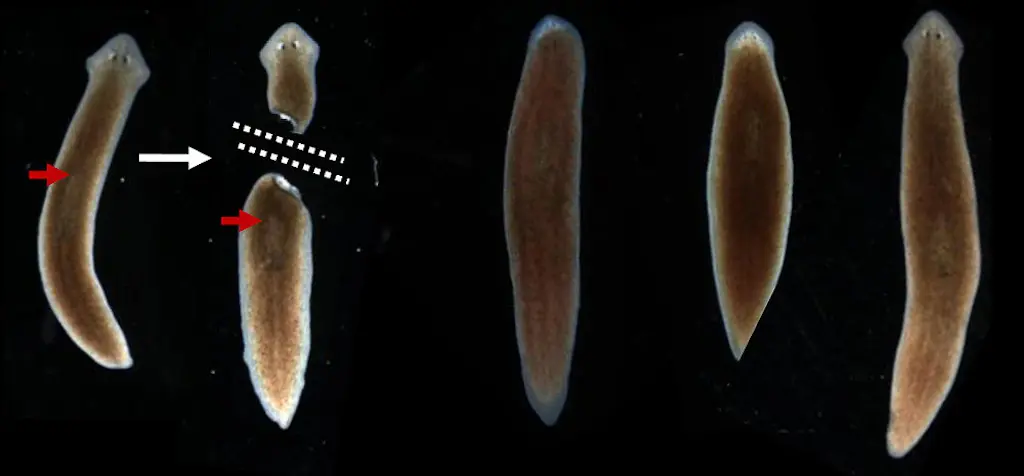

Yes, the brain kind looks like a kind of worm, coiled around and around inside the skull, slippery and wet. Perhaps the metaphor extends further. In the 60s, it was actually believed that planarium worms could encode memories in their bodies, and transfer them to new bodies. In the late fifties, James McConnell of UMich conducted experiments that appeared to show that memory transfer via cannibalism was possible in planarian flatworms.

Chop a worm into three pieces. All three pieces will regrow into new worms, and each of those worms will have the same brain, including (supposedly) the same memories. Do worms store memories outside their brains, somehow? DNA and RNA are fairly informationally dense—the haploid genome of a human being encodes about ~720mb of uncompressed data—and other chemicals and proteins can also encode things. This, as I understand, is fairly well-accepted science.

McConnell apparently figured out something weirder. He used a painful electric jolt to train worms to contract their bodies upon exposure to light. Then, he chopped them to pieces, fed the body parts to cannibalistic worms called Dugesia dorotocephala…and they contracted their bodies to light, too! Confirmation of this has been slow in coming—this the type of science the replication crisis tragically stole from us.

(McConnell, by the way, has one of those all-timer Wikipedia pages. “McConnell was one of the targets of Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber. In 1985, he suffered hearing loss when a bomb, disguised as a manuscript, was opened at his house by his research assistant Nicklaus Suino.”)

King, at least, has been struck by the image of a wormlike thing that preys on the psyche and memories and trauma of its victims. Maybe there’s just something viscerally repellant about worms.

In any case, the long boy may not be a worm or a snake. The thing Lisey regards as such might just be an appendage. An adjunct to a large (perhaps vast) body, whose totality we do not see. And furthermore, that it doesn’t eat as much as capture—that its victims might still live on.

Lisey closed her own. For a moment she saw that blunt head that wasn’t a head at all but only a maw, a straw, a funnel into blackness filled with endless swirling bad-gunky. In it she still heard Jim Dooley screaming, but the sound was now thin, and mixed with other screams.

I like the long boy. It will never be as famous as Pennywise or Randall Flagg or [Insert Thinly-Veiled Metaphor for Republican Politician Here] but that’s good. The enemy of darkness is the light, and no horror creature survives too much media exposure. As the century spins on, the long boy will retain its mystery.

(Also, what happens when you chop OpenWorm into three pieces of code?)

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.