Quick question: how many people live in Australia? About twenty-five million?

That’s right, but also wrong. Twenty-five million people don’t live in Australia; they live in Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Darwin, Adelaide, and Perth.

Leave the coastal enclaves and Australia quickly becomes indistinguishable from Mordor: arid bush, thinly grassed plains, and huge expanses of sand that can only be described as wastelands. Australia has ten deserts – new ones were still being discovered two hundred years after white fella made landfall – and they’re every color you can name. The Simpson Desert is blood-red. The Tanami Desert is orange. The Painted Desert (which contains mica) is white streaked through brown. Australians might run out of water, oil, coal, and food, but we will never run out of deserts.

Only fourteen percent of Australians live in remote areas…remote areas that are virtually the entire country. This has engendered an endless and tiresome “cultural dialog” about who the real Australians are – the majority packed into urbanities engineered to look like their European countries of origin, or the minority who actually live in Australia.

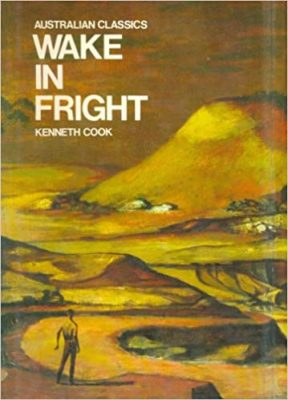

Wake in Fright is a particularly nightmarish depiction of life in the Australian outback. The main character is a schoolteacher, posted out to some flyspeck town, who has just received his Christmas pay packet. He obviously intends to return to Sydney. Citydwellers view the outback like astronauts view the vacuum of space: a cool experience, but you don’t stay past the airlock a second longer than you have to.

En-route, he stops for the night at the slightly larger flyspeck town of Bundanyabba (modelled after the real town of Broken Hill). Everyone – police, bartenders, miners – is superficially friendly in a way that’s scary, as though they’re all wearing masks. The town has secrets hidden in plain sight: moral depravity, suicide, and sexual corruption. After nightfall the schoolteacher goes out to gamble, and loses all of his money. He is now dependent on the town’s generosity to survive, and the masks start to slip.

Like Picnic at Hanging Rock, Wake in Fright was written in the 1960s, and achieved international fame through a movie. After this, the similarities end. Picnic was oneiric and hallucinatory, Wake is blunt and stark. Hanging forces you maddeningly far away from itself, In draws you close. Rock is delicately ladylike, Fright is like watching a blood and shit covered tapeworm being pulled out with tweezers from a diseased cat’s asshole.

It’s a really vile book. There’s a scene in the middle as unpleasant as anything I can recall reading, and unlike American Psycho it accomplishes this without becoming a cartoon. Even descriptions of harmless events seem coated in filth and poison. Riding a train. Eating breakfast at a hotel. Innocent acts are seen through an authorial lens that focuses the dust-cauled Australian sunlight on dust, dirt, and unpleasantness.

There’s precisely one scene where Kenneth Cook blurs the writerly camera, obscuring the action on the page. He may have been afraid of censorship. Nevertheless, there are enough clues that you understand what’s happening.

Alcohol is the grease of the story, allowing the action to move. Everyone drinks all the time in Bundanyabba, and refusing to drink is an insult. Several times the protagonist tries to plead off the beers forced on him – there’s the sense that the town is trying to poison him – and the nice bloke offering the beer turns into a spitting viper. You have to be an alcoholic in the ‘Yabba. If you aren’t, you’re an outside.

This “get drunk or else” attitude is an authentic one. Australia is a nation of social drinkers – sometimes without the social. My father used to listen to Australian country musician Slim Dusty, who wrote dozens if not hundreds of songs about alcohol, such as “You’ve Gotta Drink the Froth to Get the Beer”, “Love to Have a Beer With Duncan”, “My Pal Alcohol,” and (most famously) “A Pub With No Beer”. “The maid’s gone all cranky, and the cook’s acting queer / What a terrible place, is a pub with no beer.”

Karl Marx described religion as “the opiate of the masses”. In rural Australia, the opiate of the masses is an actual opiate.

The outback doesn’t come off looking very good in Wake in Fright. It would be considered racist if it was set in a place where the people are black or brown instead of white (as happened with Dan Simmons’ Song of Kali, and Billy Hayes’ Midnight Express). To what extent it’s modeled on reality isn’t for me to say – I’m not sure that Broken Hill was ever the antipodean Gomorrah that Bundanyabba is. But there’s romantic depictions of outback life (“Waltzing Matilda”) that seem equally alien to me, based on my limited exposure to outback towns. Maybe the needle lies somewhere in between. Maybe I am fervently planning on never finding out where.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.