Terry Gilliam’s Brazil explores the often-overlooked fact that George Orwell’s 1984 could be rewritten as a comedy with little effort.

In Room 101, Winston is tortured with his worst fear (rats). Why do this? Do they give everyone in Room 101 a personalized torture? What if my worst fear is something expensive, like having diamonds rubbed on my nipples? Why go to the trouble – wouldn’t a generic but still fearsome torture be equally effective? Why not just shoot Winston? (etc)

Brazil takes this latent absurdity, and focuses on it, enlarging it. As with 1984, absurdity doesn’t damage the film’s integrity at all. The movie’s seriously ridiculous and ridiculously serious.

It is a satire about bureaucracy grown so rampant that it throttles humanity like creeper vines. Paperwork. Chains of command. Spelling mistakes that lead to deaths. Blood-red tape. In Gilliam’s world, the future is a man filling out triplicate government forms, forever.

In real life, bureaucracy serves a valid purpose: it’s a cultural shock absorber. If I have poor impulse control, maybe I’ll think a $30,000 exhaust mod kit for my car is a good purchase. If I have to fill out 20 forms and wait a month, maybe I’ll decide I don’t need it after all. But there’s a dark side to bureaucracy: complex and multilayered systems allow responsibility to be diffused into vapor.

Brazil takes place at the furthest, blackest point of this dark side. A fly jams up a printer, turns a “T” into a “B” on an arrest warrant, and the wrong man dies. It’s not clear who’s to blame. The fly?

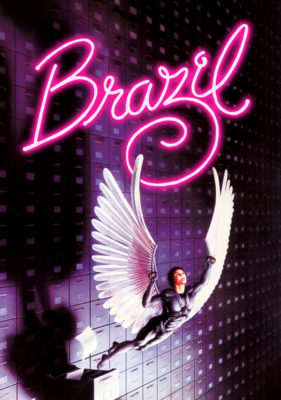

Sam Lowry is a low-level drone in a monstrous system. He is unhappy, and dreams of soaring above the world on perfect, tesselated wings. These dreams are the closest he comes to experiencing any sort of power, in a life boxed in and mangled both by a suffocating society and neurotic social set. All of the actors are good, but their main purpose is to stare obliviously at the huge, scary environment that rears up around them like prison bars.

As well he might, because the film gives you a lot to stare at. In fact, the true reason to see Brazil might be to sample Gilliam’s terrifying but strangely wondrous world.

There’s a Perry Bible Fellowship comic depicting far-future cinema-goers watching a film about World War II – full of sailing ships and medieval knights riding zebras into battle, and various other things. It’s a vivid image: all the strata of history collapsed into one because the future no longer cares about their distinction.

Brazil is a like that: it’s as if people from the year 3000 made a documentary about the 20th century. It’s both futuristic and laughably out of date. It’s chic and chintzy and garish and austere. It’s ten decades and several hundred fashions and movements mashed up together. But even this ignores Gilliam’s countless weird, inspired touches, such as the ropey, maggotlike tangles of air ducting inside Sam’s apartment. Everything looks great, with detailed sets and puppetry worthy of the Henson studio.

People in Brazil live weird, pampered lives, catered on by perpertually misfiring machines – we see one pouring orange juice on Sam Lowry’s toast. Everything always happens in the most inefficient way possible: for example, cars can only be exited by lifting up the entire roof. The one person who does his job properly is an unlicensed repairman, on the run from the law.

Brazil‘s ending is more pragmatic than 1984‘s but no less grim. In a world where all your (mis)judgement is done by the cancerous edifice of the state, there is no need to have a brain anymore. Certainly no need to use it.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.