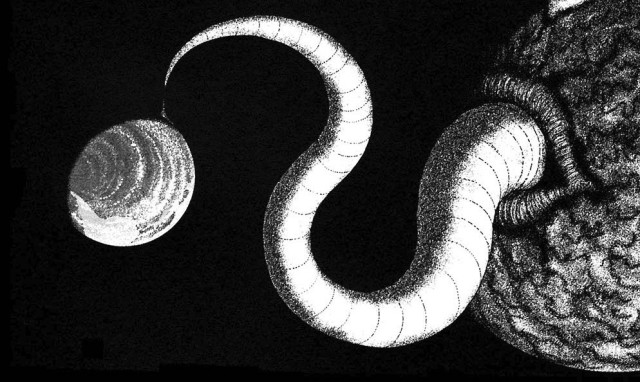

In Remina* (地獄星レミナ) Junji Ito tells a tale as old as time: girl is born; girl is named after newly-discovered star; star turns out to be malevolent planet-sized Lovecraftian entity en-route to destroy the Earth with its tongue (like we’re a Tootsie Pop and it’s finding out how many licks it takes to get to the planet core); girl spends most of the tankōbon running from deranged religious fanatics convinced she intentionally lured the planet here to lick us to death…it’s a well-worn formula, but sometimes it’s nice to relax with the classics.

I reviewed a bootleg translation of Jigokusei Remina 12 years ago. There’s now an official English release from Viz Media, and so I will review it a second time.

My review: It’s worse than I recall it being: the end.

If I gave comics a letter grade, Remina would probably get a C minus. That’s right, Mr Ito. Not even a C! A C minus! Man, I hope he learns English, and reads this review. I bet it would break him. A single tear would slide down his crestfallen face.

Even at the height of my Junji Ito fanboy phase, I was mixed on Remina (or Hellstar Remina, which is what the scanlations[1]A “scanlation” is an unofficial fan-made translations of a Japanese-language manga. As with most of Junji Ito’s work, Remina‘s path into the English language was fraught with … Continue reading called it). Following on the heels of the fish-out-of-water classic Gyo, and serialized in six chapters from 2004-2005 in Japan’s Biggu Komikku Supirittsu, It was always one of those “good enough that it really should be better” mangas: astonishingly competent in parts, yet collectively a failure.

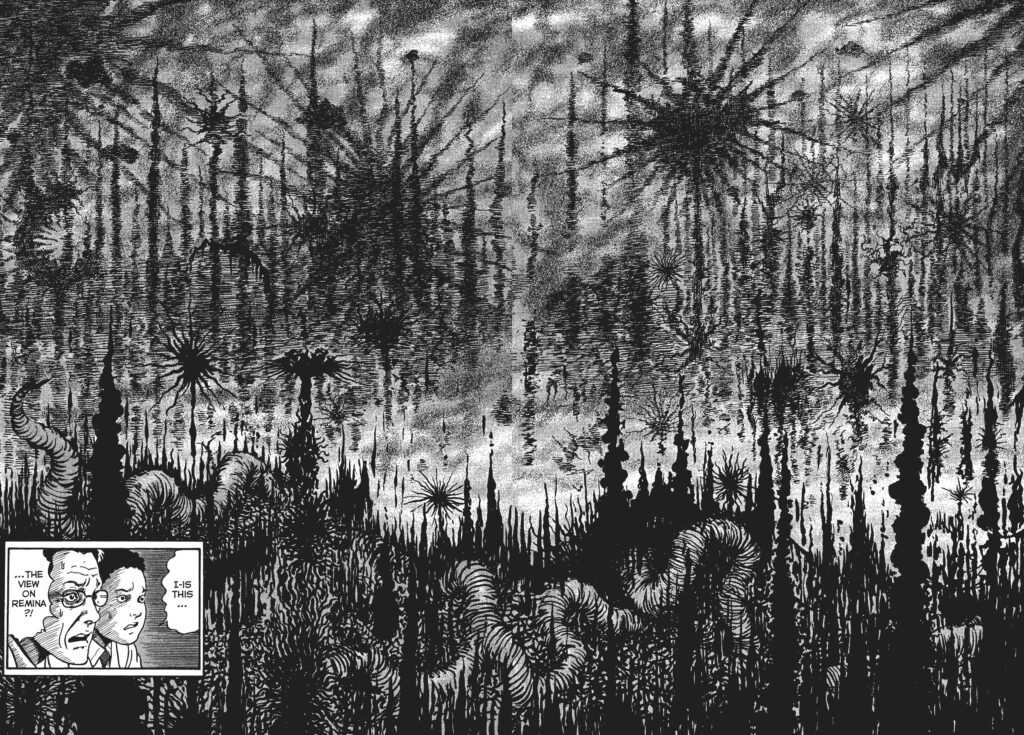

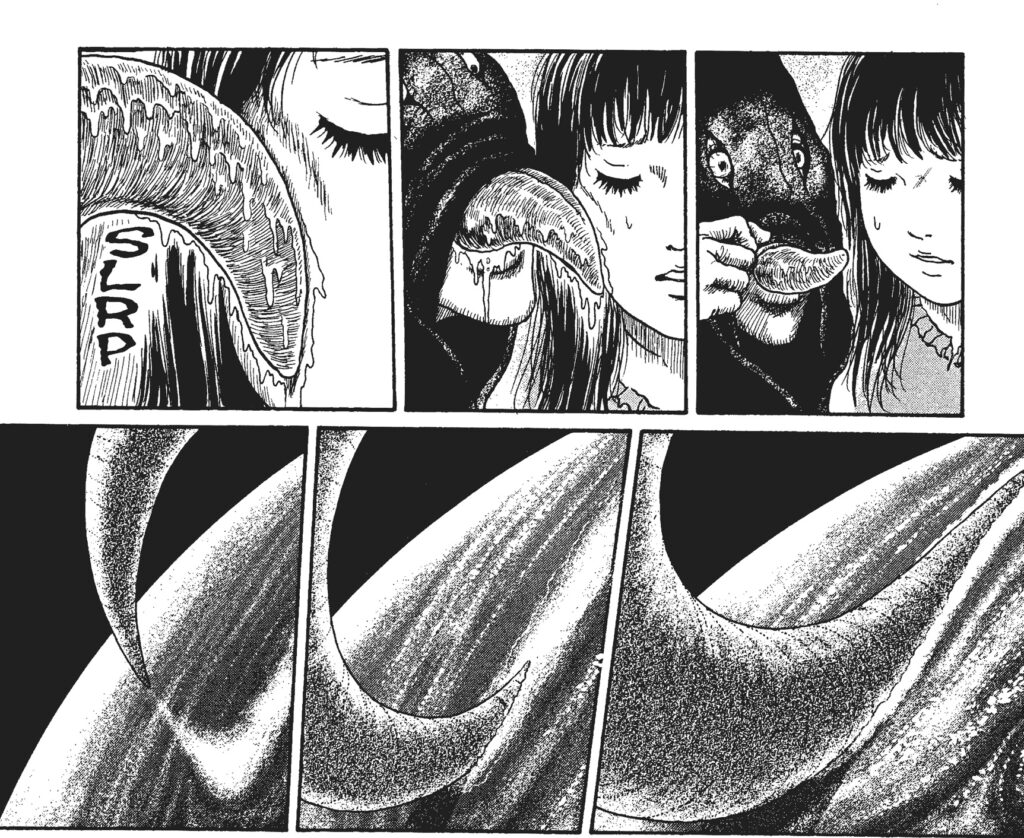

Ito-san’s viscid, squamous, cell-like art remains fucking incredible and a Cheech-and-Chong-atop-Mt-Kilimanjaro high point for the manga. Lines of black corrugate the page, like Stachybotrys mould infesting your shower and perhaps your lungs. Like most of Ito’s best work, it has a biophilic quality: the art doesn’t seem to have been drawn so much as cultivated in a Petri dish. Hopefully one that got a thorough cleaning afterward.

The editing and pacing of the panels is highly kinetic, giving the work a cinematic quality that pairs well with the loony sci-fi horror plot. Remina is packed with showstopper double-pagers, all placed with a sharp sense of drive and rhythm, going slam against your visual cortex just when the story needs a huge and thrilling needle-drop moment. We get a sense of scale when we see the hugeness of the eye staring out of Remina’s red bulk, a vivid claustrophobia in the shots of humans exploring the planet’s surface. Breathlessly paced, piling spectacle on spectacle, Remina is adrenaline printed on paper and demands to be binged in one go. It remains impressive to me that Junji puts out such complex, integrated art on a monthly schedule (or once did), with such a strong command of things like layout and pacing.

But as a story, Remina was and remains a frustrating read: a litany of opportunities missed and squandered. As an artist, he’s a master. As a writer, he frequently has no idea what he’s doing, and here he hacks off his own story’s legs at almost every turn. Many things about Remina could have worked, in theory. But they’re undermined by something else Ito tries to do.

For example:

- It’s the end of the world…but it’s a world full of insane psychopathic morons, who torture an innocent teenage girl because she has the wrong name, so who cares? Good riddance to bad rubbish.

- Remina (the girl, not the planet) is the innocent victim of a witch-hunt, and we should be on her side…but she’d need to be a character and not just a blank doll who exists to be whipped and beaten, one with no agency, or desires, or anything of her own. Bad things happen to her, and we don’t feel anything.

- *Remina* sees Ito boldly striding from his safety zone, unleashing a radically imaginative…(checks notes)…reprise of standard 1950s sci fi tropes, I guess.

Remina wears its influences on its sleeve. It has the go for broke and then when you’re broke grab your girlfriend’s credit card and make her broke too energy that the better Ray Harryhausen monster flicks evoke, but with the benefit that Ito can draw anything he wants, and isn’t confined by budgetary limitations. Old B movies hang over Remina the way the planet itself does to the characters in the story.

It’s certainly an able recapturing of the Ed Wood spaceship-is-clearly-a-model-dangled-from-a-wire era of science fiction. (We’ll be generous, and shelve discussion of whether that’s something that should be recaptured.) If that’s what you want, you’re eating. And obviously, there’s ample precedent for gonzo “you won’t BELIEVE the size of this thing that’s destroying our city!” storytelling within Japanese media itself—ゴジラ being the central example. Notably, Godzilla is classically portrayed as a saurian monster. Remina has a reptilian aspect too, particularly its forked tongue, and vertically-slitted eye. (The horrific planet overwhelmingly looks human, though, which makes thematic if not logical sense.)

But the story’s most direct evolutionary ancestors are Sakyo Komatsu’s 1973 novel Japan Sinks (where an implausible scenario is described in the terse language of a governmental disaster report) and Kazuo Uemetsu’s Fourteen (a bewildering apocalypse manga where the world seemingly ends in every way imaginable at once). Junji Ito has spoken of highly of Komatsu and Uemetsu as artistic influences, so that’s one possible Rosetta Stone for Remina: a homage to the stories that shaped him.

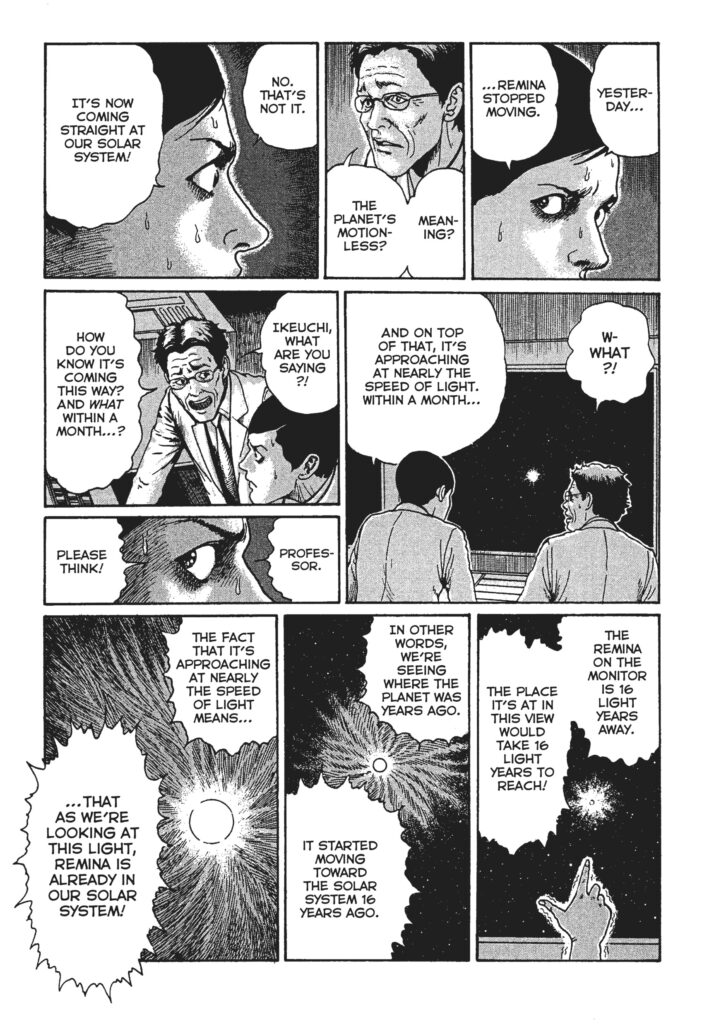

But Ito’s storytelling is too loose and too “monthly manga” to nail the hard sci fi tone of Komatsu. Everything about Remina’s setting is just an incoherent mess that survives zero logic and exists largely just to set up the next showstopper visual piece. Remina isn’t hard sci fi. It’s so soft it achieves negative digits on the Mohs Scale. This is one of those stories where astrophysicists explain the speed of light to each other.

And although Kazuo Uemetsu (who sadly passed away in 2024) remains Junji Ito’s favorite mangaka (and is praised in every interview the man gives), I have never detected much of the “Umezz” style in Ito’s work. At its best, Fourteen is just a firehose of unchained ideas, disgorged stream-of-consciousness style at your retinas. It was exhausting, and I do not plan on re-reading it any time soon, but it left the same impression on my consciousness that a severe fever might. I was changed by it. Remina is far less fun and spontaneous. It feels planned, calculated. But if that’s so, why plan this?

I think Remina needed to be eerie and dreamy and surreal, not literal and logical. It needed to show us a bizarre, impossible doom overtaking the world without explaining that doom to death at every turn.

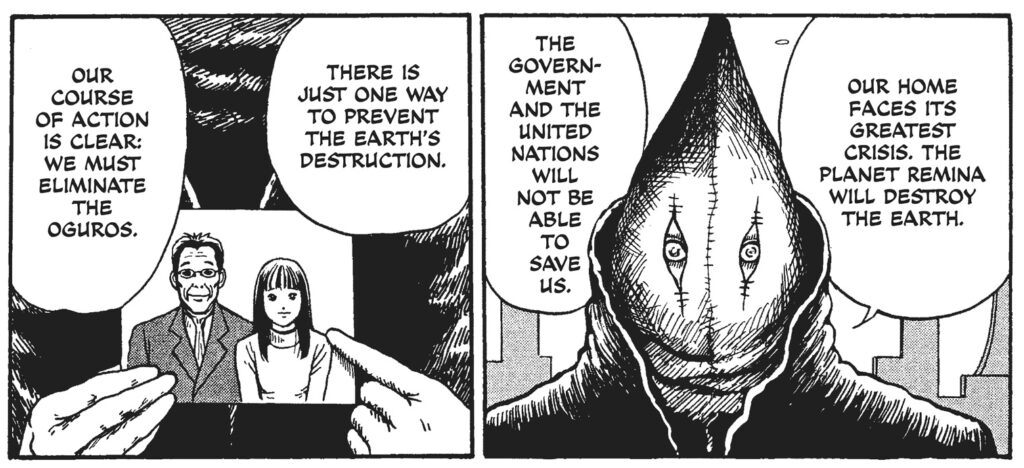

Remina offers no ambiguity. On every other page (particularly in the first two volumes), we get Exposition Scientist characters offering verbose narration on what’s happening with the planet (always with camera angles helpfully showing the planet’s approach), ensuring that we see the entire plot in 4K hi-def. And believe me when I say that Remina‘s plot does not stand up to close scrutiny.

If you want to make a scary horror comic about a planet that may be alive, we don’t need to see the planet disgorging a cartoon tongue. You’re rubbing our faces in the story’s weakest aspect: the scientifically implausible setting and story. I wish Ito had focused more on tone and mood, instead of a regime of visual literalness. Perhaps he should have confined us to one character’s viewpoint: someone on the ground, maybe. I know I’m “punching up” Ito’s work to an annoying degree, but if this manga’s events happened to you in real life, you’d probably have no idea what was going on. You’d understand the unfolding disaster as a series of ruptures in your daily life. Strange piercing noises from out of space. An unendurable jangling in your teeth fillings. Vast and horrific shadows drifting monstrously across the voided face of the clouds. The internet would either crash or be packed with contradictory nonsense: a screaming madhouse, its inevitable silencing a mercy-killing. If you had a radio, it would blast out a blizzard of static until you shut it off to save your remaining marbles. You would not know what to trust or to believe. Certainly, you would not trust your own eyes.

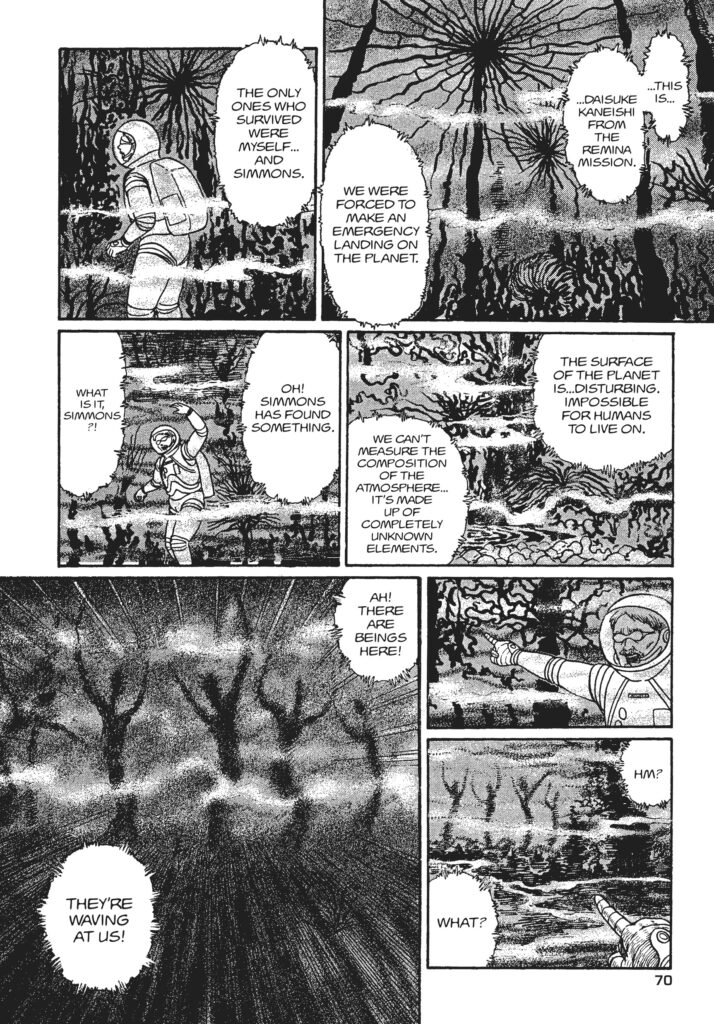

That’s the tone Remina left me hungry for. One of uncertainty, with mankind crossing the L1 Lagrange point of something truly inexplicable. The best part of the comic might be the scene (brief but compelling) where astronauts land on the planet, and literally cannot comprehend what’s happening there. They think they see people there…people waving.

But this is seldom the tone Remina goes for. Instead, it shows what should remain hidden.

Stephen King wrote something perceptive about the flaws of visual mediums such as films. Their strength—their ability to connect directly with the reader’s senses—inevitably becomes a weakness, as the audience will start focusing on technical flaws, and trying to pull apart the effect (which we know ultimately comes from a puppetmaker’s workshop or a CGI rendering farm ). As he put it (On Writing)…

Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s. When it comes to actually pulling this off, the writer is much more fortunate than the filmmaker, who is almost always doomed to show too much . . . including, in nine cases out of ten, the zipper running up the monster’s back.

Yep, that’s Remina. 261 tankobon-format pages, slowly zooming in on the monster’s zipper.

In 1980 Stephen King wrote a novella called The Mist (first published in the Dark Forces anthology and later reprinted in his own 1985 Skeleton Crew collection).

Thematically, it runs a similar line to Remina. The outer narrative is that a government experiment went horribly wrong and plunged Anytown USA into a liminal half-world shrouded in mist. The mist is the important thing, as it prevents the characters from establishing a rapprochement with their new environment. King recognized that monsters you see aren’t half as scary as monsters shrouded in fog—visible as a limb, a tail, a tongue.

Occasionally (more frequently as the denouement looms), characters in*The Mist glimpse some of the full and horrible extent of the changes that have swept over their world. But they never see the full picture, and what they do see is blurry. This makes parts of The Mist horrifying in a grounded, believable way that Remina never approaches in its blitzkrieg attack on your limbic system. His description of a colossal creature, taking unbelievably large strides through the mist—is one of the most memorable setpieces in a Stephen King story. You feel the ground shake when that thing’s six impossible feet land around the characters.

At about twenty past one—I was beginning to feel hungry—Billy clutched my arm. “Daddy, what’s that? What’s that!”

A shadow loomed out of the mist, staining it dark. It was as tall as a cliff and coming right at us. I jammed on the brakes. Amanda, who had been catnapping, was thrown forward.

Something came; again, that is all I can say for sure. It may have been the fact that the mist only allowed us to glimpse things briefly, but I think it just as likely that there are certain things that your brain simply disallows. There are things of such darkness and horror—just, I suppose, as there are things of such great beauty—that they will not fit through the puny human doors of perception.

It was six-legged, I know that; its skin was slaty gray that mottled to dark brown in places. Those brown patches reminded me absurdly of the liver spots on Mrs. Carmody’s hands. Its skin was deeply wrinkled and grooved, and clinging to it were scores, hundreds, of those pinkish “bugs” with the stalk-eyes. I don’t know how big it actually was, but it passed directly over us. One of its gray, wrinkled legs smashed down right beside my window, and Mrs. Reppler said later she could not see the underside of its body, although she craned her neck up to look. She saw only two Cyclopean legs going up and up into the mist like living towers until they were lost to sight. For the moment it was over the Scout I had an impression of something so big that it might have made a blue whale look the size of a trout—in other words, something so big that it defied the imagination. Then it was gone, sending a seismological series of thuds back.

Did “the mist only allow them to glimpse things briefly”? Well, no. The writer (playing God unseen) did that, because he judged it would be more effective if the story was told this way. He was right.

By contrast, Ito’s world shows too much, and becomes weightless and cartoony and unreal, despite the masterful art. “Mehr licht!”, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is said to have cried on his deathbed. “More light!” Remina needed weniger licht—less light.

Ito makes his ramshackle sci-fi setting support social commentary about fame and celebrity. This is a dubious idea on the face of things, but the commentary only hits shallow obvious points anyway. Did you know there’s a dark side to fame? That your fans might turn on you at any moment? There’s a twist at the end involving the president of Remina’s fan club, a twist both unlikely and on-the-nose.

The protracted horrors of the book’s middle section feel gratuitous and lazily cynical, much as some of Alan Moore’s work does (in my view). It feels truly implausible that so many people would be out to get Remina, just because of her name. Ito’s satiric barbs fail to stick in the skin because this is not what people do. Six years after Ito released this comic, the Great East Japan Earthquake flung forty-meter tsunamis against Japan’s Iwate Prefecture. Twenty thousand people died. The reaction was not anarchy and mobocracy (and the killing of random young women who shared nominative determinism with the tsunami), but an reasonably orderly and effective response. This seems to be the norm when disaster strikes—our culture’s “humans are fundamentally evil” narratives are mostly founded on things like Kitty Genovese—hoary nuggets of “everyone knows” pop culture wisdom that have grown much, much bigger in the telling than they were in reality. Things like PizzaGate are small, ineffective, and usually seem more like social clubs for crazy people (who tend to alienate their real life friends and family) than effective movements.

Ito may have intended a feminist reading of Remina: the central character has not done anything to deserve a hate mob, except have a certain name (a name and role assigned by the ur-patriachal figure of her father). But again, she’s such a nonentity, such a generic made-to-order victim, that it’s impossible to feel anything for her. Toward the end, I started to sympathize with the mob a bit. Yeah, no shit they care about Remina’s name. It’s the only noteworthy thing about her!

Ito has never been one to overload his female leads with character development (his famous anti-heroine Tomie is defined by a lack of a character—in the earliest story she’s clearly an innocent victim of male obsession, in later stories she’s more of an evil succubus figure, in Tomie Returns she’s a “monster of the week” with powers that seemingly change with the story Ito wishes to tell). But on my first read, I wondered if Remina’s blankness might be intentional—Ito setting us up for a twist ending, where she turns to face the other characters, and her human face is gone. Swallowed. Replaced with the horrific cloud-chained visage of the planet Remina, and only the planet Remina. Because the hate mob was right. This blank of a girl was the the living avatar of the hell planet.

Remina is worth getting to complete your (legal) Junji Ito collection. Fast-paced and forgettable, it does not display Ito at his best.

The most enjoyable parts were (again) the pair of scenes where characters explore the surface of Remina. These work great as self-contained horror pieces, and they’re certainly disgusting and gruesome. They also do not feature the girl Remina at all. That could be a clue as to what doesn’t work about this volume.

Viz’s edition lacks my favorite part of the original Japanese release—the concluding standalone short-story 億万ぼっち, or Okuman botchi. The title has been translated various ways. Army of One. Lonely Billionaire. Billion Lonesomes.

The story itself is fantastic: an inspired horror riff on the way antisocial loners view interaction: as bodies being stitched together; in horrific forced intimacy.

It’s clever, surprisingly subtle for such gruesome material, with actual intelligent things to say about social isolation and loneliness in the age of mass media. (I could have done without the final panel.) It connects back in time to the Japanese “Hikikomori” phenomenon (it could also be read in light of Volker Grassmuck’s classic “I’m Alone but Not Lonely” essay, which details otaku culture specifically), and forward to things like involuntary celibates,

Army of One‘s ending, like Remina’s, makes no sense when read literally, but unlike Remina’s, it works well metaphorically. When I read some incel theorypoasting about how Staceys don’t want good kind lads (like him), I can’t escape the knowledge that he has never experienced the thing he claims to desire. He’s attracted to the idea of having a girlfriend. Suppose a girl actually asked him on a date…how would he find the experience? Would he enjoy it? Or would it make him shudder—yet more flesh stitched into flesh? Be wary of climbing unknown mountains. There might not be breathable air at the top.

As I’ve said, this story is not present in Viz’s Remina. Maybe because already collected in the earlier Venus in the Blind Spot. Maybe, too, because it upstages the main event.

References

| ↑1 | A “scanlation” is an unofficial fan-made translations of a Japanese-language manga. As with most of Junji Ito’s work, Remina‘s path into the English language was fraught with challenges and setbacks. The first chapter was scanlated by brolen9104, then abandoned after nobody donated to read more. The rest of the book was scanlated by Daniel Lau (a talented writer in his own right—what became of him?).

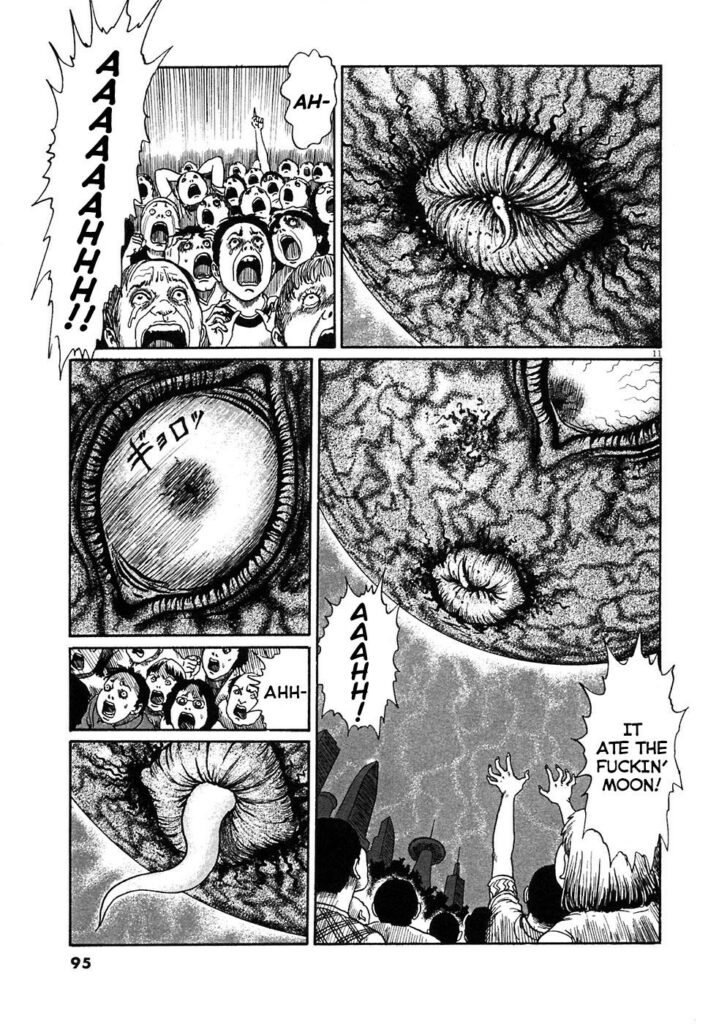

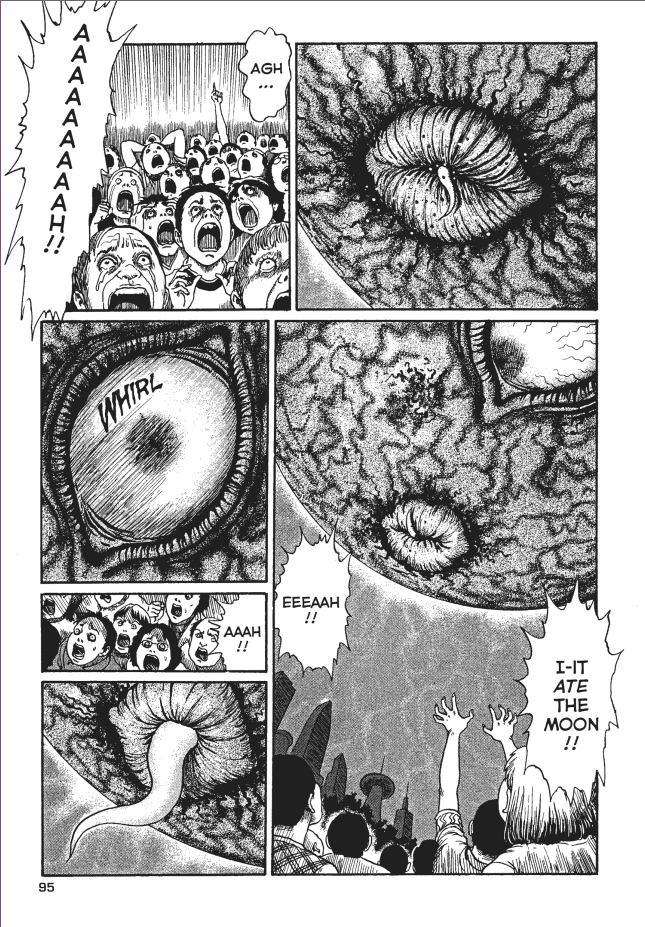

Most online piracy sites awkwardly linked the two scanlations together, starting with Brolen’s ch1 and continuing with Lau’s ch2-6 (a big faux pas in the manga pirate community—you’re supposed to post scanlation projects as completely as possible, rather than changing horses mid-race). You can tell which is which because brolen translates Ch1 as “The Ugly Star” and Daniel Lau translates it as “The Dread Planet”. Viz’s translator Jocelyne Allen renders it “Vile Star”. Daniel seems to have thought the manga worked best as a straight-up farce. I love the guy’s dialog here. “It ate the fucking moon!”  https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-568x800.jpeg 568w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-209x295.jpeg 209w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-768x1082.jpeg 768w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP.jpeg 994w" sizes="(max-width: 727px) 100vw, 727px" /> https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-568x800.jpeg 568w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-209x295.jpeg 209w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP-768x1082.jpeg 768w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tp2vP.jpeg 994w" sizes="(max-width: 727px) 100vw, 727px" />In Viz’s edition, it becomes this:  https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Clipboard02-557x800.jpg 557w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Clipboard02-205x295.jpg 205w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 645px) 100vw, 645px" /> https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Clipboard02-557x800.jpg 557w, https://coagulopath.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Clipboard02-205x295.jpg 205w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 645px) 100vw, 645px" />How boring! |

|---|