Pets can tell when their owners have died, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. It’s true. Happens all the time. Joe Bloggs goes into cardiac arrest, and at that precise moment his adoring dog Fido will get up and take a shit on the front lawn. Something it was going to do anyway, but now it’s a mournful shit.

Pets can tell when their owners have died, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. It’s true. Happens all the time. Joe Bloggs goes into cardiac arrest, and at that precise moment his adoring dog Fido will get up and take a shit on the front lawn. Something it was going to do anyway, but now it’s a mournful shit.

I think I might share this psychic link with certain celebrities. Occasionally a name will pop into my head, and I get worried. Many people in my mental Rolodex are old and in bad health. So I’ll immediately ask Dr Google for a prognosis: are they still alive?

Sometimes they’re not. David Gemmell wasn’t. Tom Clancy wasn’t. Often they’ll have died weeks or months earlier, which weakens my claim to psychic ability.

But sometimes, as now, the prognosis is good. Harlan Ellison is still alive! In fact, he recently published a new book. It’s called Can and Can’tankerous. He’s more than alive, he still has his workclothes on.

He’s a writer who has spent nearly sixty years producing output in forgotten wastelands – first 1950s pulp fiction, TV shows, a few comic scripts, even a computer game – he seems attracted to media with a brief expiration date. He’s known for filing suits and (in the case of Connie Willis) groping them. He’s a strange creature, a narcissist who can be self deprecating (one of his collections has the endearingly honest subtitle “Seventeen Stories Written Before I Got Up To Speed”).

He’s also proof that you can be too good at self-promotion.

Becoming a funny dancing monkey is always a successful marketing strategy, but it’s no good as a long con – at the end of the day you don’t actually want the attention on yourself, but on your art. Rebecca Black’s art is now completely ignored – she was only valuable as a brief cultural zeitgeist, forgotten and disposed of once we found other dancing monkeys to gawk at. I don’t even have the courage to see what the Numa Numa Guy is doing now. Probably trying to launch an actual musical career. I feel depressed just thinking about it.

H.E. is different, yet in a sense, he isn’t. There’s a line of demarcation between selling a product and providing a spectacle. Harlan Ellison spent a career straddling that line blowing raspberries.

He’s so over the top and ridiculous that Nick Mamatas draws a distinction between “Ellison stories” (which means H.E.’s science fiction oeuvre) and “Harlan Stories” (stories about Harlan, the man). H.E. presumably wants the world to care more about the Ellison stories than the Harlan ones. My impression: maybe the Harlan ones are winning out. It’s hard to find in-depth commentary on his science fiction (and much of it has gone out of print). But man, the internet won’t stop talking about that time he got fired from Disney after four hours of work.

Ellison’s fascinating in a way that sometimes overshadows his work. But as I said, he does a lot of work in fields that lack longevity – how many Mickey Spillane paperbacks have you bought in the past whenever? Does your heart bleed from the loss? I don’t know if Ellison’s stories will disappear from our culture’s memory the way Spillane’s have. I think that his most famous efforts (“Repent, said the Etc”, “I Have No Mouth and I Must Etc”) will survive the memory hole for a long time, but someday even they will be forgotten.

But there’s a certain sad poetry in impermanence, and beautiful things that die quickly.

Think of the female mayfly, which rises from a swamp and lives for only about thirty minutes. Its compound eyes open, take in their surroundings…and then close. Forever. Its wings unfurl, beat upon the malarial air, and then are still. Only the swamp that spawned it remains.

Maybe Ellison knows what he’s doing, and maybe he’ll even have the last laugh. He’s cultivated an impressive amount of art, and maybe we could include Ellison himself in that body – a demonically charming man, both irritating and unforgettable.

Barthes wrote about the “Death of the Author”. Well, here’s one author that isn’t dead, and still won’t be dead when they put him in the ground. That might have been the plan all along.

The Powerpuff Girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice. This would have been disturbing a medieval person, for spices were used to disguise the taste of rotting meat (…according to 21st century backfills of history. If you could afford cinammon from Cathay and saffron from the Indies, you’d think you could afford fresh meat.)

The Powerpuff Girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice. This would have been disturbing a medieval person, for spices were used to disguise the taste of rotting meat (…according to 21st century backfills of history. If you could afford cinammon from Cathay and saffron from the Indies, you’d think you could afford fresh meat.)

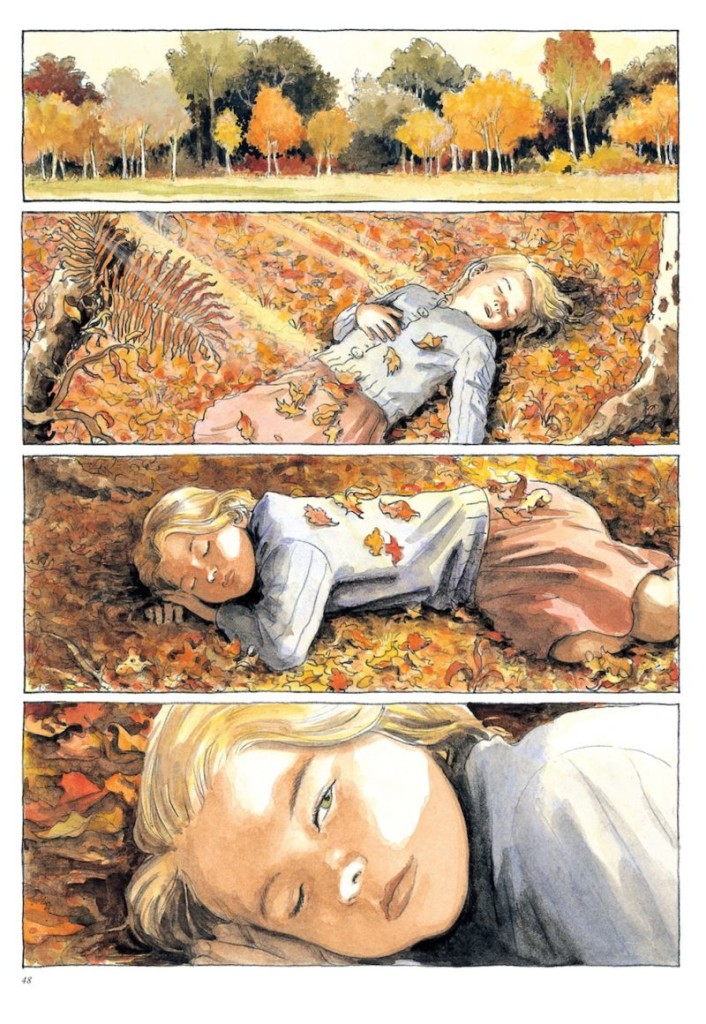

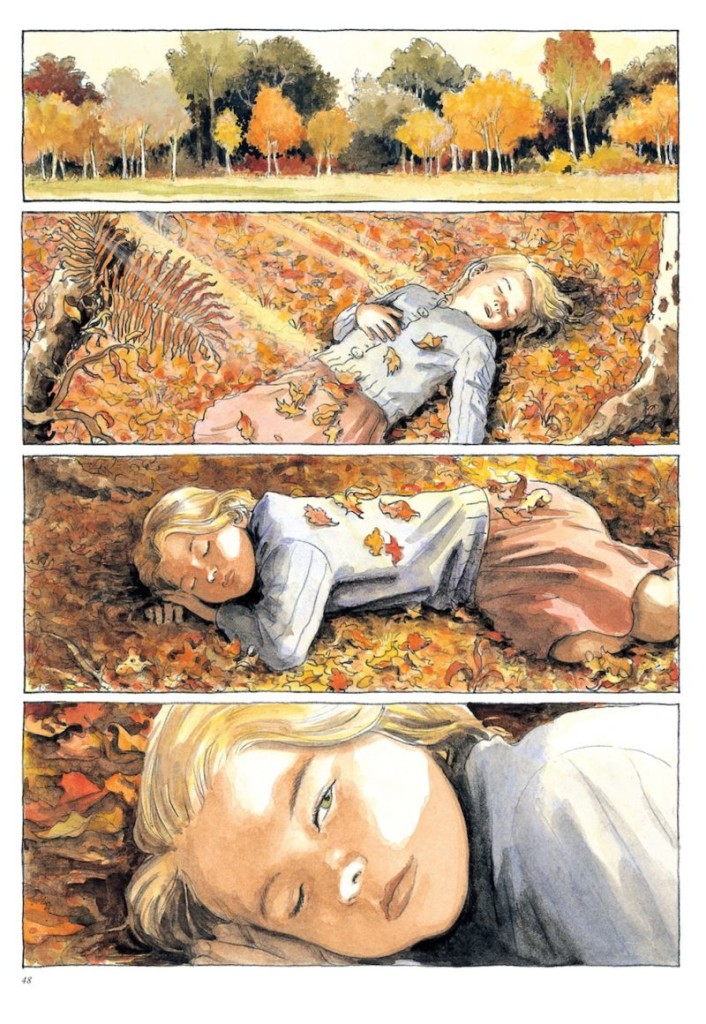

When something must be made of spice for it to be palatable, what’s it hiding? Where’s the decay? How deep do I have to go before I draw back the knife and there’s black corruption on the blade? Many classic fairytales hardly wait at all before brutally traumatising you. This graphic novel is a classic fairytale told in a very arch and self-aware way – you can see the blows coming a little bit, but they still hurt.

The backstory: a young girl creates a host of whimsical characters in her head. After she dies in an unexplained accident on a country trail, these characters escape her head, and must start a new life in the woodlands.

The plot’s events resemble William Golding’s book Lord of the Flies mixed with Kazuo Umezu’s manga The Drifting Classroom. Lots of characters die, both to the environment and to each other. Many are stupid, useless, or poorly-adapted – one-note characters that spill from a dead girl’s earhole into an many-note world. Even the smart and skilful ones have lots of trouble staying alive. They try to establish a new society, but it doesn’t work very well. Nothing does.

My sister used to wonder what cartoon characters do when we’re not watching them on TV, and what computer characters do when the system is switched off. Beautiful Darkness shows us. It makes you want to leave every electrical appliance switched on 24/7, so that they’ll never be outside their element again.

Various new characters get added to replace the dead ones – a mouse, and later a woodsman, who of course remains oblivious to the tiny creatures running around his hut. By the time the final showdown between two rival females occurs, so much has passed and the characters have become so twisted that we forget their whimsical beginnings.

The art is good – very splashy and expressionistic, lots of going outside the lines in a way that can be used both for blushing petals and pools of blood. The writing is adequate – apparently it’s translated from another language.

I liked Beautiful Darkness. It holds your attention while you’re reading it, but some of its more disturbing implications only arrive when you put the book down. That dead girl’s corpse must smell pretty bad on that country trail. You’d wonder that the woodsman never discovers her body – or, if he does, why he never tells anyone. Maybe he doesn’t want her to be discovered.

There’s one hit wonders that really only have one hit. Then there’s hits that cause collateral damage – the force of the hit lifts some of their other work into pseudo-hit status as well. After The Knack scored a hit with “My Sharona” they had one or two other singles limp along to the backwaters of the charts. Nobody was fooled. They were a one hit band.

There’s one hit wonders that really only have one hit. Then there’s hits that cause collateral damage – the force of the hit lifts some of their other work into pseudo-hit status as well. After The Knack scored a hit with “My Sharona” they had one or two other singles limp along to the backwaters of the charts. Nobody was fooled. They were a one hit band.

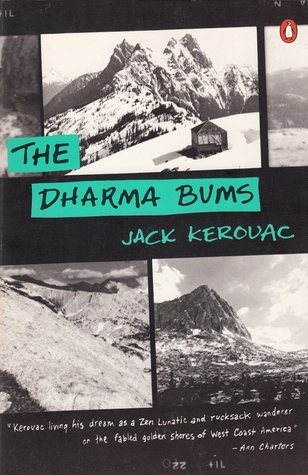

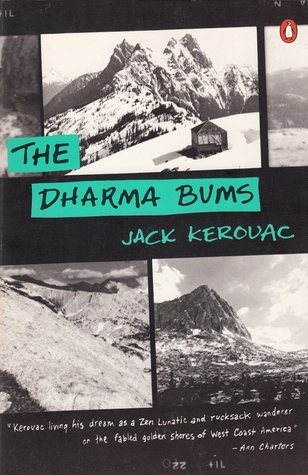

On the Road, a confusing novel that captured a cultural era, was Jack Kerouac’s hit. If you’ve read any of his other works, you have that novel to thank. The Dharma Bums comes across as a sappy, maudlin coda to that book – where he shows that he’s not just a crazy hellraiser, he’s also sensitive and spiritual.

Or…something. Beat Generation books are notoriously difficult to analyse, because it’s a movement that prizes nebulous emotions and epiphanies instead of actual ideas and content. Want to be “Beat”? Feel vague inklings of belief that never coalesce into a creed. Experience vague feelings of dissatisfaction that never ferment rebellion. Play “The Times They Are a-Changing” on repeat, learn to play the sitar badly, and study the Noble Eightfold Path while pounding THC into your system. Congratulations. You are now “Beating Off.”

The Beat Generation could never make a positive or negative case about anything. There’s the feeling that applying sanity and epistemology destroys the magic of the thing. This is certainly a valid way to feel, especially when you’re young, but it’s difficult to translate that feeling into a book. When you refuse to clarify or firm up anything beyond a laconic “soak in the vibes, man!”, you often end up with a book about nothing.

The Dharma Bums almost but doesn’t fall into that category. It’s a short book about nothing.

This feels like it was written for children. It’s a series of simple, unexamined actions, blaring like a note on a cheap Casio keyboard. We’re climbing a mountain! We’re riding a car! These mundane activities are described in paroxysms of joy and religious ecstasy.

And the food. There’s so many descriptions of them eating that it’s like Brian Jacques’ infamous Redwall books – again, books for children. Have you ever noticed that food fulfills the role in children’s books that sex fulfills in adult books? If the luxurious descriptions of food in the Dharma Bums were sex acts, this might be the most censored book in American history.

There’s exactly one moment – the suicide of a fragile female character, I believe – where it seems like Kerouac’s getting ready to do something. I was still waiting for this something when I turned the last page of the Dharma Bums. Ultimately, you’re left with a book that seems to satirize the delirious, masturbatory emptiness of the Beat experience – except it doesn’t seem to have been written as a satire.

On the Road wasn’t a great book it was better than this: a mild-mannered ramble through mid-50s Americana that not only pulls out the Beat Era’s fangs, but pulls out every other tooth as well. The Dharma Bums is so soft and repetitive that it’s like being gummed to death. The Dharma Gums.

Pets can tell when their owners have died, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. It’s true. Happens all the time. Joe Bloggs goes into cardiac arrest, and at that precise moment his adoring dog Fido will get up and take a shit on the front lawn. Something it was going to do anyway, but now it’s a mournful shit.

Pets can tell when their owners have died, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. It’s true. Happens all the time. Joe Bloggs goes into cardiac arrest, and at that precise moment his adoring dog Fido will get up and take a shit on the front lawn. Something it was going to do anyway, but now it’s a mournful shit.