How much control do artists have over their work? Are they like, Yen Sid, conjuring miracles with a master’s hand? Or are they like Mickey Mouse, magic erupting haphazardly from their wands, praying everything goes right?

How much control do artists have over their work? Are they like, Yen Sid, conjuring miracles with a master’s hand? Or are they like Mickey Mouse, magic erupting haphazardly from their wands, praying everything goes right?

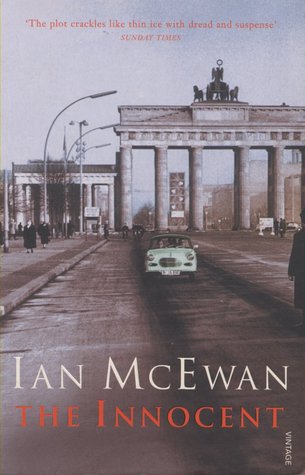

Basically, when this book goes off the rails, was it an accident or was it Ian McEwan’s plan from the start?

The beginning is compelling. It’s the 1950s, and a British electrical engineer is flown out to help a covert American spy operation in West Berlin. Russian communications all pass through the city before being routed back out to the Kremlin. It’s thought that by digging a tunnel into East Berlin and installing monitoring equipment there, US and British intelligence can obtain an electronic peephole through the Iron Curtain.

He’s young and naive. The Americans don’t trust him. McEwan weaves fictional and nonfictional elements together, and soon he has the makings of a promising spy novel. But soon, he meets a German woman, and some “horizontal collaboration” occurs. She’s already married, to a semi-vagrant all-alcoholic who beats her. Probably par for the course when a woman burns a steak in the 1950s, of course, but since Maria doesn’t cook steak I guess the beatings are on the house. One day, this husband discovers the affair, and all hell breaks loose.

I don’t know what to say about the book’s romance elements. Midway through it almost forgets about the compelling spy background and just focuses on Maria and Leonard’s assignations full time. They’re long, not super interesting next to the spying, and it’s disheartening to see the book’s remaining pages get relentlessly pared away by this stuff.

I’ve never liked an overemphasis on romance in art. People find it fascinating for some reason, maybe because they’ve had more experience at it than me, and they’re able to color the fictional descriptions with their own memories. To me, the coloring book remains closed. The experience of love is essentially an emotional common cold: you have it, then eventually you don’t. It’s a mundane thing that happens to thousands of people every day. Who cares? Digging underneath the Berlin Wall to intercept Kremlin communiques – now that’s what I want to hear about.

The book eventually shows its colours as a meditation on innocence. Even this comes off as unsatisfying, as the story’s backdrop is too huge and interesting for a low-key bildungsroman to work. The war is growing colder. Stormclouds gather. Friends sharpen knives for each other. Against all this, you’ve got a guy learning to have sex? That’s the sort of thing that gets made fun of on the @GuyInYourMFA twitter account. “My protagonist is only referred to as ‘the boy.’ On the final page? ‘The man.'”

But everything except the foreground elements are really well done. Why couldn’t McEwan have focused more on the things that were working, instead of forcing in something that fundamentally doesn’t?

I guess the romance actually was the main point of the book, and the spy context is just a backdrop. That makes The Innocent the most disappointing kind of presents: the one where the packaging is more interesting than the contents.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

The book is called “Submission”, not “Rebellion”. Expected notes of defiance or insurrection aren’t found here. Nobody hides a dagger inside a niqab or hijab. The heart of the matter is this: Michel Houellebecq doesn’t think Western culture is worth saving. His take on an Islamist takeover of France is something like “good, you deserve it.”

The main character is incidental: a middle-aged literature professor who lays pipe in various female students (apparently Houellebecq wasn’t very successful with the fairer sex when he was young. He’s certainly making up for lost time in the pages of his books). Blearily, as if through a panopticon, we see the political stormclouds rattling France. In order to obstruct a right-wing takeover, France’s Socialist party is allying with the Muslim Brotherhood, turning them from a wedge party to an actual force. Soon, Francois sees the future: Islamist Mohammed Ben-Abbes will be president of France.

Scenes of Francois’s daily life are deliberately flat and empty, like slashed tyres. Things like microwaving dinner end up being little manifestos of ennui. Houellebecq hits you hard with pointlessness of it all, and although he almost superglues his tongue inside his cheek (one of the places Francois stays is the site of the Battle of Tours in 732 ad), it’s hard to call this book satire, unless it’s satire with an incredibly broad target: like western civilization or perhaps sentient life as we know it.

The book came out on the 7th of January. On the same day, two Al-Qaeda shooters blessed and culturally enriched eleven magazine publishers in France. For all Houellebecq’s contempt for Islam (“the stupidest religion”, as he says), it’s never dealt with him as it has with Charlie Hebdo, or even Salman Rushdie. Indeed, it’s mostly his fellow westerners that have caused him problems, charging him with hate crimes and forcing him into exile and all the rest of that business.

On one hand, Islam occupies a central role in Submission. On the other hand, it’s hardly in the book at all. French decadence is Houellebecq’s real target. Islam, as he sees it, is just a memetic predator in a world full of memetic predators – it’s the responsibility of guards to stay at their posts and keep the predators out. And France has found her guards asleep at their posts.

After Charlie Hebdo, I assume people rushed out to buy Submission, expecting solidarity and French pride and saber-rattling, and were a little surprised by what they got.

It’s not that Houellebecq’s writing is dark. Lots of writers are dark. The thing is that you never know where you stand with Houellebecq, or are sure of what he’s truly saying. I don’t mean that in an obscurantist postmodern sense. I mean it in the sense of Hitler’s quote “You will never learn what I am thinking. And those who boast most loudly that they know my thought, to such people I lie even more.” Houellebecq’s work is full of crypto-Marxist and crypto-reactionary asides and allusions, like squid ink to conceal his true views. What, finally, is Houellebecq’s stance? That France needs to recover its spine? That’s too easy.

His mind is a black box, and so is this book.. In the end, the only thing I can draw from the soil of Submission is that France can probably no longer with saved. He’s a bit like Martin Amis, who was born in the UK but has permanently relocated to the US. Sometimes you can take the jungle out of the boy.

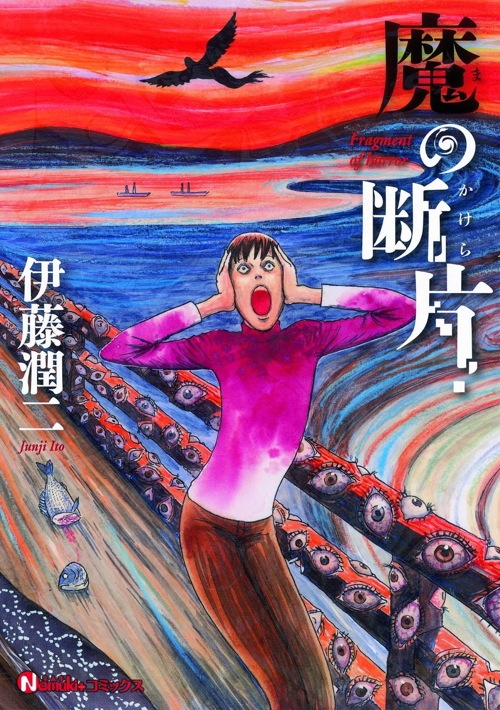

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.

Why doesn’t he age? Clearly, black magic is afoot. I don’t know the specifics of his deal with the devil, but I’m they involved eternal youth, in exchange for nobody ever being able to translate him to English.

The evidence is overwhelming: the landscape is littered with failed attempts to get this man in English. In 2001, ComicsOne licensed his 16-volume Horror Collection series, released the first three in English, and then vanished from the face of the earth. In 2006, Dark Horse licensed his 12 volume Museum of Terror collection, again released three, and then cancelled the series for reasons unknown. In 2011, an online manga website called Jmanga opened with Ito’s Voices in the Dark as one of its launch titles…and folded, less than two years later. Most recently, Ito was conscripted to work on Silent Hills, and then the project was given a brutal gangland-style execution by Konami. The Junji Ito Curse is not to be mocked.

Viz has licensed several Ito properties in the past, and (perhaps foolishly) has now given us one more: Fragments of Terror. Frankly, I think they are now living on borrowed time. You don’t bring Junji Ito to English and escape the consequences. I expect to wake up tomorrow and find that they’re filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, their headquarters have been overrun with flesh-eating spiders, and their CEO’s athletes’ foot is flaring up.

Fragments of Terror collects one-shots from the last few years of Ito’s pen. They’re a mixture of inventive JG Ballardian concepts, scary campfire dread, horror movie camp, and Ito’s excellent art. Not everything in here is great, and it doesn’t disguise the “serial manga fingerprints” as well as it might, but it’s still a worthy addition to the slim lineup of English Ito titles.

Affairs start with “Futon”, a story about a mattress that induces hallucinations when you sleep on it. Not one of Ito’s best efforts. Very dull and one obvious, with a pat, tie-a-bow-on-it ending. “Wooden Spirit” is stronger, with Ito drawing an inspired link between the curves of a woman’s body and the natural geometries of plants, trees, et cetera. No real attempt at a story, but the execution and art is impressive.

Issues of tone from one story to the next soon jump out at the reader. The understated “Wooden Spirit” gives way to the comical and gruesome “Tomio – Red Turtleneck”, followed by borderline shoujo bait in the sappy and sentimental “Gentle Goodbye”, followed by the ultra-violent “Dissection-Chan”. The stories whiplash erratically from one mood to the next. Why put the stories in chronological order? Why not take advantage of the opportunity to craft a bit of an arc, to build and release tension?

The best and worst story in the collection sit right next to each other. “Magami Nanakuse” involves a girl journeying to meet a mangaka she admires, and then…well, remember “Ghosts of Golden Time”? It’s that crap all over again. Very awkward and ham-fisted attempts at social commentary here, as well as a lack of focus or direction.

But “Blackbird” is a great. Intelligent, well paced, scary as hell. A man is rescued after apparently spending a full month trapped in the wilderness with two broken legs. How has he survived his ordeal? Things keep building and building, and the ending satisfies without explaining too much. I’d put this story up against anything from Ito’s classic period (1997 to 2002 or so).

In the end, if nothing else Fragments of Terror offers a statement to the fact that, despite all the events of the last ten years (marriage, fatherhood, pacts with the devil, etc), he’s still capable of serving up the goods. He’s still in love with waifish female leads, elaborate dresses soaked in blood, grotesque imagery, and stories that make no sense but have you nodding in perfect agreement.

Ito might be in cruise control mode, but he’s still here, and Fragments of Terror is an interesting if uneven collection from an underrated mangaka who’s still making inroads to the English market. No doubt Viz’s corporate headquarters will be smoking and charred rubble by tomorrow, but they did a good job here.

How much control do artists have over their work? Are they like, Yen Sid, conjuring miracles with a master’s hand? Or are they like Mickey Mouse, magic erupting haphazardly from their wands, praying everything goes right?

How much control do artists have over their work? Are they like, Yen Sid, conjuring miracles with a master’s hand? Or are they like Mickey Mouse, magic erupting haphazardly from their wands, praying everything goes right?