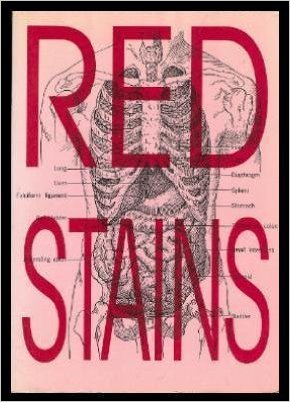

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.

The best one is the reprint of Ramsey Campbell’s, “Again”, which features flies, a corpse, and a gestalt: a terrifying and suffocating sense that you’re lost in a repetitious and unending cycle. Autoerotic strangulation via Moebius loop. Creation does come across as a “getting all my buddies in print” vanity enterprise at times (it helps if you understand that many people in this book don’t exist, and are pen names for other authors), but writers like Campbell and Burroughs hint at an ambition to be more than that.

Terence Sellers furnishes an excerpt (from The Correct Sadist) that is short and twisted. Not fifty shades of gray, one shade of black. David Conway’s story “Eloise” (which you can find collected in Metal Sushi) melds the old and romantic with futuristic anodyne and chrome. I’d already seen this story in one of his collections but was glad to read it again. Is this its original printing?

Then there’s “James Havoc”, contributing “In and Out of Flesh”, a fragment which appears in a more polished form in his Butchershop in the Sky compilation (and again as a full-blown graphic novel form in 2009). A teenage biker gang commits sadistic sex murders, literally writing return to sender on the bones of their victims. This early version is oddly unHavoclike – adjectives are relatively few, there’s no wild Burroughs-esque “literary guitar solos” a’la Satanskin, and generally it’s more like a story than is usual for this writer. The end of the collection promises a forthcoming (and still unreleased) children’s book from Havoc called Gingerworld, which (again) appears in fragments in Butchershop in the Sky.

Then there’s the usual filler. James Havoc’s girlfriend. A blink-and-you’ll-miss-it excerpt from Jeremy Reed. Prose from Clint Huczulak. Poetry from Aaron Williamson. They fulfill one purpose: increasing the page length beyond chapbook size into an actual anthology. None of these works were memorable in any way.

The final story, Paul Marks “And the Sun Shone by Night”, woke me from my torpor with its sheer brutality. Its first few pages make it sound like a a heavy handed tract about animal testing, but the following content is so extreme that goes straight past being a moral fable and becomes a Gommorral fable, if you like. Who’s Paul Marks? His generic, unGooglable name makes me think he’s still another pseudonym.

Red Stains is a nice look at the prime years for one of Britain’s early “extreme fiction” publishing houses. While their later compilation Dust emphasises surrealism, this one focuses on gore and violence. These were good times for Creation. In later years, a more apropos title would be Red Ink.

Here’s the problem. In 1933, Walt Disney adapted the classic tale of the Three Little Pigs into an animated short. It was an unexpected crossover success. Audiences loved the pigs, and loathed the wolf, who they saw as a symbol of the Depression. “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” became a national rallying cry. Disney made some other shorts starring these characters, but somehow they didn’t make the impact the original did. His verdict: “you can’t follow pigs with pigs.”

Here’s the problem. In 1933, Walt Disney adapted the classic tale of the Three Little Pigs into an animated short. It was an unexpected crossover success. Audiences loved the pigs, and loathed the wolf, who they saw as a symbol of the Depression. “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” became a national rallying cry. Disney made some other shorts starring these characters, but somehow they didn’t make the impact the original did. His verdict: “you can’t follow pigs with pigs.”

CS Lewis follows pigs with pigs here – or to be more exact, he follows pigs with a single half-sized runt of a pig that has mange, watery eyes, and a cracked hoof.

Why does this book exist? It’s not bad. It just doesn’t make a case that it ever needed to be written. Narnia is again under the yoke of oppression, and the Pevensie children have to save it. Usually when writers re-tell the same story, they up the stakes, often to the point where it becomes ridiculous (the Rocky series eventually had Sylvester Stallone going twelve rounds against international communism). Prince Caspian does the reverse, lower the stakes. Why?

This is a 5% milk version of TLTWATW . Queen Jadis was evil incarnate, King Miraz is a unmemorable fop. Once the fate of the world hung in the balance, now we’re resolving an dispute of Narnian regency. Exciting! Caspian never seems heroic or kingly – he does nothing except blow a horn and invite the Pevensies back to Narnia, where they immediately take over and virtually evict him from his own book. Even Lewis’s imagination fails to find cruise control mode: there’s no bits of whimsical imagery like the lamppost in the forest, or the faun with the umbrella.

It didn’t have to be this way. Prince Caspian could have been its own book, like the later Narnia titles. The hooks are all there. For example, we know the Pevensie children grew to adulthood in Narnia, before returning to their own world and their childhood bodies. How did this affect them? Apparently it didn’t. They still talk and act like upper middle class British schoolchildren. Why weren’t they transformed and left alien by their experiences? Why wasn’t their return to the human world marked by misbehavior and disassociation as they struggled to adapt? There’s so much material for a story here, so why did Lewis run a repeat?

There’s two great scenes in this book. The first is the early scenes between Caspian and Dr Cornelius – it’s exciting and well-paced, the way the conspiracy unfolds little by little. The second is the chapter “Sorcery and Sudden Vengeance”, where a disgruntled dwarf tries to overthrow Miraz by bringing the spirit of Jadis back. Unusually intense and almost diabolical – moments like this are why not all Christians are comfortable with Lewis’s subject matter. “No one hates better than me.”

Two exciting moments, that hint at Lewis stretching himself as a storyteller and a thinker. The rest of the book is like a musician working the scales. In a way, the title seems to refer to the book’s own stature. It’s a Prince, but TLTWATW remains the king, and it has no enchanted horn to blow.

“One trick pony” is usually used in a disparaging way, but really, it depends on how good the trick is. Drugs are a one trick pony, but based on various after school specials I’ve seen, they’re certainly worth doing, and are probably the only thing worth doing.

“One trick pony” is usually used in a disparaging way, but really, it depends on how good the trick is. Drugs are a one trick pony, but based on various after school specials I’ve seen, they’re certainly worth doing, and are probably the only thing worth doing.

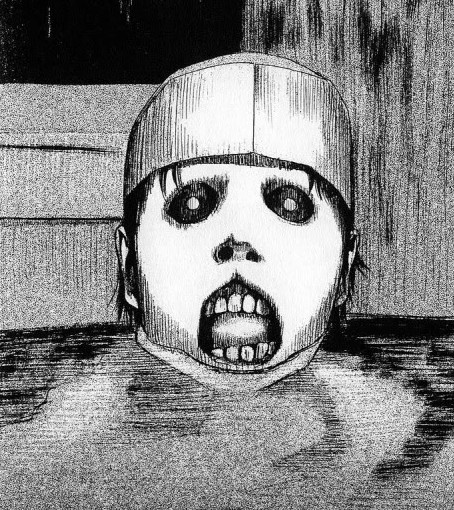

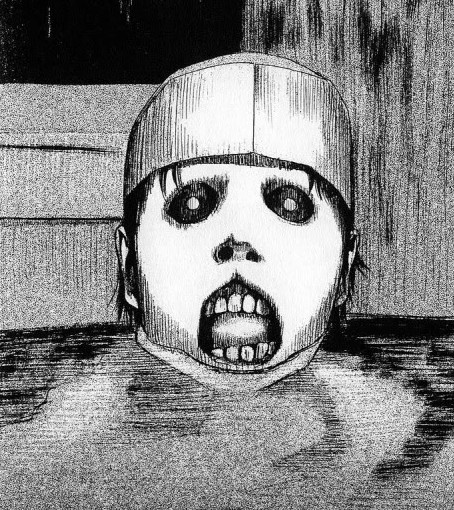

Fuan no Tane is the ultimate one trick manga. It’s a barrage of ghost tales and urban legends, 3-4 pages each, with no characters, no stories, and sometimes hardly any text. Like snowflakes, none have much effect on their own, but when they come at you as a blizzard, you soon feel very cold. And addicted. It’s hard to stop reading Fuan no Tane, but I recommend it in only small doses. You can’t exactly marathon this stuff, it’s like too many dances with China White, you overdose at a certain point and your brain shuts down.

If you were raised on urban legends about men with hooks for hands and killer toilet seat spiders, you’ll feel right at home here. Some are brutal and gory, with “The Ear-Slashing Monk” being the most memorable in this category. Others have a strong element of camp. Still others bypass camp completely, and enter a Daliesque world of postmodern absurdism. “The Eyes that Seek”, for example, involves an army of detached eyeballs rolling down the highway.

Japanese humor notoriously inaccessible to Westerners. I don’t know if these ghost stories are Japanese in origin, or if Nakayama has adapted western material, but the terror impulse is probably far more universal than laughter. A lot of these are definitely creepy – although some of the cartoony ones do take the edge off the proceedings a little. It’s a great formula from a quality assurance standpoint, too. It doesn’t matter that some of the chapters fall flat, because there’s another one straight away to take the taste away.

Nakayama followed this up with Fuan no Tane Plus (aka, More of the Same™), and more recently Kouishu Radio, (aka, More of the Same™: The Samening, Electric Boogaloo). I think this might be the only trick he’s capable of.

None of which matters to an addict, of course.

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.