Have you ever listened to a conversation in a foreign language? That’s what sexual fetishes are like. They’re exciting if you speak the language. If you don’t, you’re left watching two people make noises with your mouth, your brain struggling to pattern-match their syllables against some meaning until eventually you give up.

Have you ever listened to a conversation in a foreign language? That’s what sexual fetishes are like. They’re exciting if you speak the language. If you don’t, you’re left watching two people make noises with your mouth, your brain struggling to pattern-match their syllables against some meaning until eventually you give up.

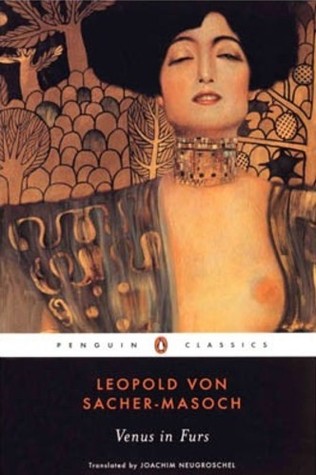

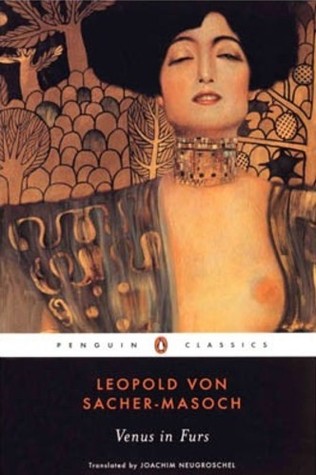

I don’t find BDSM interesting, so much of Venus in Furs is a conversation in Putonghua or Sundanese. After I gave up trying to follow the conversation, I looked for a story, and there wasn’t much of one.

It’s a book within a book. A man reads a text about a “supersensual” man, Severin von Kusiemski, who falls under the spell of a woman with the South Park-sounding name Wanda von Dunajew. She wears furs. She captivates him – literally. He wants to be her slave. They go away on adventures together. The tone of the book feels like cordial that’s on the verge of fermenting into poison: a fantasy pushed as far as it can go.

Venus in Furs contains frank descriptions of a lot of things that would not have names for decades to come. It’s also unfocused, and suffers from the curious comorbidity of too much and not enough. The plot’s repetitive, with events looping around like a 12 inch record caught in a groove. But von Sacher-Masoch keeps adding in all these asides about metaphysics and gender roles and paganism, throwing the novel’s forward momentum into a talespin.

Sacher-Masoch likes to set up bowling pins and then forget to knock them down. Partway through the story, a few black female slaves assist Wanda in humiliating Severin. Could that have led to a reflection on real bondage? And the shallowness of what he experiences with Wanda? After all, Severin can reclaim his freedom and dignity whenever he wants, whereas some people can’t. BDSM’s just a fantasy, which is good in real life, but in a fictional book, why couldn’t he have gone beyond fantasy? Why not talk about real bondage? Venus in Furs dwells obsessively on saccharine instead of real sugar.

Apparently in BDSM there is a concept called “topping from the bottom”, where the submissive person uses the fact of their submission as collateral to manipulate or control the dominant. “I gave up my freedom for you. You really owe me, so let’s run this relationship on my terms.”

I’m the furthest thing from an expert, but Severin seemed like he was topping from the bottom a lot. One of his first acts is to make Wanda sign a contract of his servitude, stating among other things that she must always wear her furs. This adds a false, insincere dynamic to their relationship: like putting someone in chains and giving them the key. It’s like von Sacher-Masoch was topping me from the bottom. The book lures you in with the promise of revelation, intimacy, and one man exposing his secret heart. He immediately starts offloading mountains of ruminations on gender roles and metaphysics and paganism. This book could be subtitled “Dear Diary.”

The fetish-as-language metaphor breaks down. When you hear an unfamiliar language, the problem is that you don’t understand it. With a sexual fetish, you understand it perfectly well, it just has no meaning. After it’s possible to learn a new language, but I don’t know that it’s possible to learn a new fetish. If you can, Venus in Furs is no Berlitz Easy Language course.

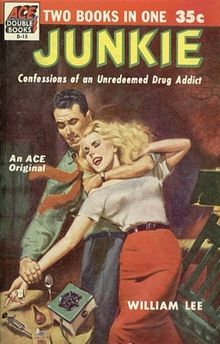

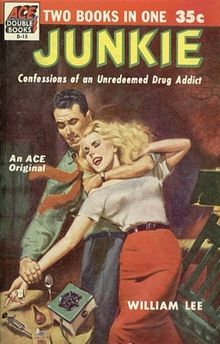

Before Burroughs decided his purpose in life was to beat the English language like a bitch who owed him money, he was writing things like this – a sane, lucid, and readable pulp novel about his addiction to heroin. Books about drugs often have a hallucinogenic quality, as if they’re trying to give the reader a second hand high. This isn’t like that. Burroughs is offering his body as a testing ground: he puts substances into it and writes about it in analytic terms.

Before Burroughs decided his purpose in life was to beat the English language like a bitch who owed him money, he was writing things like this – a sane, lucid, and readable pulp novel about his addiction to heroin. Books about drugs often have a hallucinogenic quality, as if they’re trying to give the reader a second hand high. This isn’t like that. Burroughs is offering his body as a testing ground: he puts substances into it and writes about it in analytic terms.

This was shocking in 1953. In 2015, not so much. Rich trust fund brat pulls the silver spoon from his mouth and starts cooking coke on it: stop the presses. Even if it’s not a pack of lies like A Million Little Pieces, the story is very familiar. I feel like I’m reading about a man’s disclosure of sexual envy and mid-life ennui. We get it. This is not special.

Its interesting if you want to know more about drug culture in America before Vietnam, Iran-Contra, crack cocaine, and all the rest. But really, not that much happens in it. Burroughs describes how he got involved with the scene, the interesting characters he met, and his occasional run-ins with the law. Beyond that, he doesn’t tell us much. This isn’t an exploration of man’s dark heart, it’s a police report.

Subsequent re-issues have tried to shoot steroids into the story with lurid, impressionistic cover art. But the original Ace Books cover art best captures the spirit of the tale: a man struggling with a woman, who has knocked a hypodermic syringe out of his hand. This is the most dramatic incident in the book, and even then it’s not all that interesting. Burroughs’ sexual proclivities are written about in the same dry way – he throws in off-handed mentions about boffing men, and then its back to scoring drugs. I was curious for more. These details about his life could have been expanded upon, and expounded upon. Instead, we get sketches.

But Junky has some moments where Burroughs really hits paydirt and gives us something good. I liked his description of being a drug addict. Paraphrased, it goes something like “I didn’t take drugs to get high. I took drugs to be functional. Heroin meant I could brush my teeth and shave myself and put on clean clothes. That was my high.” Pleasure operates at a tight Malthusian limit: no matter how much you dump into the brain, once a habit starts there will never be enough. I was reminded of a rotten.com article on crystal meth, and how quickly you degrade to a state where basic, mundane life is impossible without it.

Moments like that are chinks in the armor of Junky, and I wish there were more. Right now, it seems like a paradox – a tell-all book that tells almost nothing. I was hoping for more insights, more details, more specifics on what it’s like to be a man like Burroughs in the 1950s. I wonder if the good stuff was left on the cutting room floor: this was a different age for publishing, just as it was for everything else.

I suppose you could argue that Burroughs promotes a positive social message by making drugs look boring.

Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?

Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?

This is shit, guys. I got 7 Billion Needles in 2012. Junji Ito was in one of his periodic 2-3 year “releasing fucking nothing” dry spells, and this looked vaguely similar. What I got managed to be not what I expected via the contradictory path of being EXACTLY what I expected: cliche after cliche after cliche, hammered down with the repetition of a judge’s gavel.

This is the swill that passes for horror manga? Even a novice to the form like myself could pick up on all copy-of-a-copy ideas. “Main character fuses with a symbiote and fights monsters”? Off the top of my head: Parasyte, Variante, Tokko, and Genocyber…and I read LESS THAN ZERO manga. Main character’s an alienated high school girl? Be careful, I’m not sure Western markets are capable of handling this much originality.

The story is better recapped by someone who cares more than me (ie, anybody). The character design is workmanlike and boring. The art is full of computer-assisted gradient shading and all the other parlour tricks of a bored pen monkey cranking out a generic serial to an editor’s cracking whip. The plot has a lot of…events, you could call them. Things happen. Then they stop happening. Repeat for a few hundred pages. Launch franchise.

7 Billion Needles is apparently inspired by Needle, by Hal Clement. The storytelling is not reminiscent of any era of Western science fiction, just a very standard manga formula that’s executed neither better or worse than average, and doesn’t stand out even by being a train wreck. Cripples inspire pity: bores inspire no reaction at all.

When I think of horror manga, I think of Kazuo Umezu’s doomed worlds, Shintaro Kago’s gross-outs, Suehiro Maruo’s nihilism and aesthetics, Jun Hayami’s brutality, Junji Ito’s fetishistic HR Gigerisms…even Hideshi Hino’s primitive efforts have more panache and charm than 7 Billion Needles.

The title comes from a metaphor: the difficulty of finding a particular needle amongst seven billion other needles. This also describes the experience of anyone trying to find decent manga in this day and age.

Have you ever listened to a conversation in a foreign language? That’s what sexual fetishes are like. They’re exciting if you speak the language. If you don’t, you’re left watching two people make noises with your mouth, your brain struggling to pattern-match their syllables against some meaning until eventually you give up.

Have you ever listened to a conversation in a foreign language? That’s what sexual fetishes are like. They’re exciting if you speak the language. If you don’t, you’re left watching two people make noises with your mouth, your brain struggling to pattern-match their syllables against some meaning until eventually you give up.