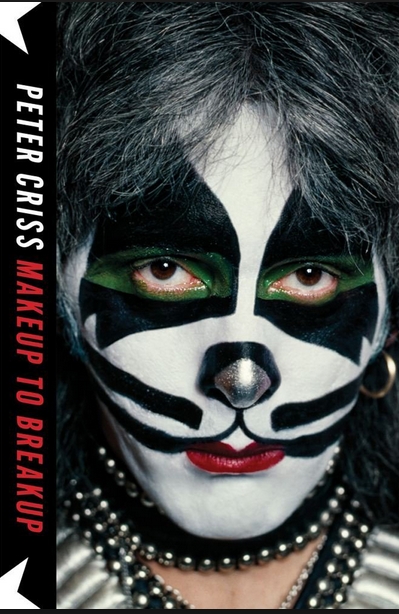

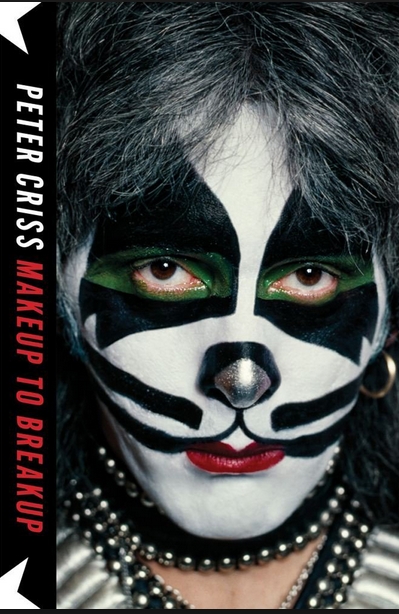

Filed under the bookstore section called “Lifestyles of the Rich and Blameless”, this is the KISS drummer’s attempt to set the record crooked. The KISS breakup soap opera has no shortage of pointing fingers, but Peter Criss adds all eight of his own, plus two (non-opposable?) pointing thumbs, and a pointing toe. Gene’s an asshole, Paul’s an asshole, Ace is an asshole, his grandma’s an asshole, the IRS together comprises an asshole…nothing’s ever Criss’s fault, is it? At its best, the book is revealing and honest. Sometimes it’s shallow and manipulative, 384 pages of PR management. And it was ghost-written, which adds another obfuscating layer between the reader and the truth.

Filed under the bookstore section called “Lifestyles of the Rich and Blameless”, this is the KISS drummer’s attempt to set the record crooked. The KISS breakup soap opera has no shortage of pointing fingers, but Peter Criss adds all eight of his own, plus two (non-opposable?) pointing thumbs, and a pointing toe. Gene’s an asshole, Paul’s an asshole, Ace is an asshole, his grandma’s an asshole, the IRS together comprises an asshole…nothing’s ever Criss’s fault, is it? At its best, the book is revealing and honest. Sometimes it’s shallow and manipulative, 384 pages of PR management. And it was ghost-written, which adds another obfuscating layer between the reader and the truth.

It opens in 1994. Criss is in a filthy bedroom in LA, down to his last hundred thousand dollars, and getting ready to shoot himself. The barrel of the gun is in his mouth when he looks at a picture of his daughter, and he hears God telling him not to do it. The scene is overcooked and not entirely convincing. Then we go back to the beginning, when a young man called Peter Criscoula joined a band called Wicked Lester, which changed its name to KISS, recruiting Bill Aucoin, and emerged as the hottest act in rock (figuratively and otherwise. The time when Gene Simmons set himself on fire is described with some glee)

There’s some big laughs in this part of the book: like when the band discovered that their live show had finally received a positive review…from a gay lifestyle magazine. But ultimately you can’t say that Peter “Catman” Criss ever fell out of character, for Makeup to Breakup is indeed catty: proof of this comes early in the book, where he slams Paul and Gene for their “revisionist KISStory”. This is the start of a lot of ripping on his erstwhile bandmates, which starts out funny and then becomes less so.

Makeup to Breakup is certified masturbatory material if you hate “Gaul Stimmons” (Paul is described as semi-gay, with a fixation for men’s dicks. Gene is presented as a power-tripping megalomaniac who belongs in a room with padded walls), but for heaven’s sake, at least those guys wrote music. What did Criss ever do? “Beth”? That was someone else’s song. He didn’t vibe with the band musically (he recalls hearing a tape from Wicked Lester and thinking it was too heavy for his taste), and his personality clashed with everyone. Add in his well-documented substance issues and you have a hors de combat member of the KISS Army.

Criss’s problem is that he was boring – and that is the one thing rock stars can never be. They can suck at their instruments. They can be narcissists and egomaniacs. They can be brazen criminals. But they can not be boring. Criss was smaller than life, the dullest member of the band, possessed of a fragile, neotenous face and quintessentially inadequate drumming skills. His career highlight was really someone else’s highlight. He even had the most boring character.

Criss wasn’t a rock star, he was more of a rock meteor…a brief flash in the night sky, and then an anticlimactic cooling lump displayed in a museum for the next forty years. Say what you will about Gene and Paul, but THEY are KISS. All Peter Criss did was keep the drummer’s stool warm for a while, and this memoir exposes it totally.

I cannot find the direct quote, but Haruki Murakami’s translator said something to the effect that you should never learn a second language, because it will make you realise how much your favorite foreign-language books were corrupted in the translation. I don’t think this would be much of an issue with Borges’ writing. There’s a timelessness about his stories, as if they’re not constructed from fragments and morphemes but from ideas. So long as a language recognizes the basic building blocks of logic, Borges’ tales can be translated to and read it in.

I cannot find the direct quote, but Haruki Murakami’s translator said something to the effect that you should never learn a second language, because it will make you realise how much your favorite foreign-language books were corrupted in the translation. I don’t think this would be much of an issue with Borges’ writing. There’s a timelessness about his stories, as if they’re not constructed from fragments and morphemes but from ideas. So long as a language recognizes the basic building blocks of logic, Borges’ tales can be translated to and read it in.

This book collects most or all of Borges’ “fiction”. This makes for a varied read, but varied is the rubric of everything Borges’ wrote. This collection is everything at once, all the time. Alternate history runs into proto-Ballardian speculative fiction, which bows out for poetry and fantasy and essays. Erase the front and back cover and this could be an anthology by at least five separate authors.

The first section is A Universal History of Infamy – tales of swashbuckling and adventure that blend history and mythology in the same way as…actual history. These stories are thematically shallow but action-packed and exciting. Borges apparently didn’t think much of this book, but what did he know?

Then we get to the the two legendary collections – Ficciones and The Aleph. What can I say about them? Try to understand them and you will only get part of the truth. Try to describe them and they will sound distorted and ruined on your tongue. Try to imitate them and you will fail. This is partly because of Borges inimitable style – direct, yet coy – but it’s mostly because these stories are about things truly beyond human comprehension. The human figures in his stories seem dwarfed, like ants gathering food in the shade of the Colossus. Even the stories that don’t invoke mathematical infinity have a larger-than-life quality about them, such as the haunting “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, which evokes similar feelings of cosmic dislocation as Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and more gracefully too.

The tales from The Maker are slightly less ambitious but are entertaining and thought provoking. There’s “Borges and I”, probably the only story I’ve read that’s in the both the first and second person simultaneously, and “Toenails”, a disturbing musing on one’s body parts. It’s the sort of thing that might have appeared on Jorge Luis Borges’ blog, had such a thing been possible.

There were better writers of philosophy (numberless), better writers of fantasy (a lot), better writers of horror (a few), and better writers of speculation fiction (one or two), but nobody else was a jack of this many trades. He was even a master of pithy quotes (“a fight between two bald men over a comb” – on the Falklands conflict). Almost everything in this collection is entertaining, and everything is the operational word here. Other writers are like tiles in a floor. Borges is the cement poured between the tiles – connecting everything, joining all. Now come, membership at the Library of Babel awaits.

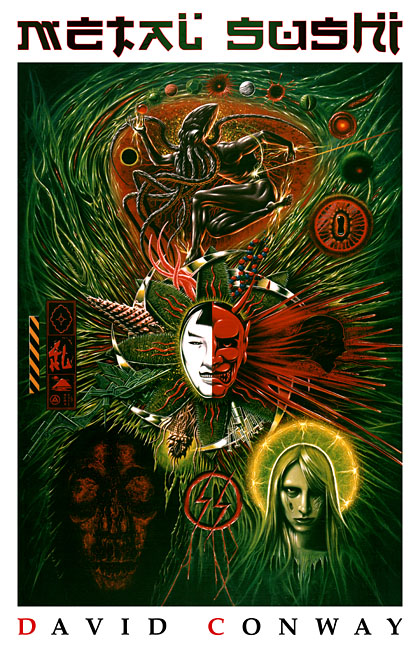

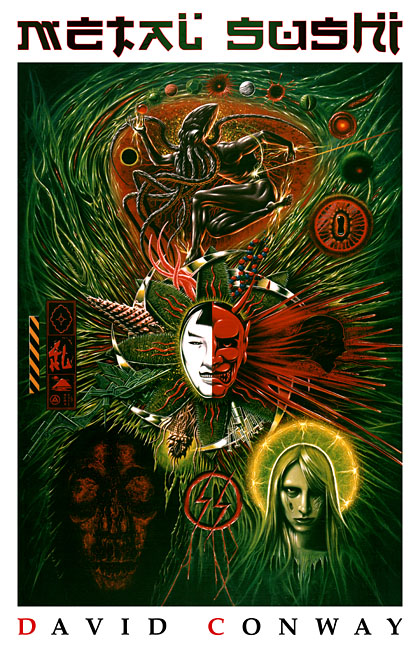

Starry Wisdom had a story called “Black Static”, by David Conway. It wasn’t the best story in the collection, but it was the defining story – the one that kind of spoke for the others. Then I read Starry Wisdom‘s sequel and “Manta Red” went one better – it was the defining story of the volume and the best one.

Starry Wisdom had a story called “Black Static”, by David Conway. It wasn’t the best story in the collection, but it was the defining story – the one that kind of spoke for the others. Then I read Starry Wisdom‘s sequel and “Manta Red” went one better – it was the defining story of the volume and the best one.

Metal Sushi contains both these tales, and four others. Conway’s work could be described as the bang-from-behind bastard children of surrealist literature and those ultra violent 90s anime where the human body is a bag containing about twenty gallons of pressurized blood. He throws a lot at you – lots of themes, lots of ideas, and lots of dense, adjective-stuffed prose.

The first story is “Eloise”, which is like an Oscar Wilde or Edgar Allan Poe story performed in modern dress – very dark and romantic. “Black Static” is more chaotic and challenging, and extracting meaning from it feels more like deciphering tea-leaves than the normal reading of a story. “Manta Red” (the greatest story in this volume, too) is the interstice between the two.

This collection gathers all of Conway’s strengths as a writer, but it gathers all of his weaknesses, too. Metal Sushi suffers from “too much”, particularly “too much writing.” Certain parts sound like the kind of thing they make fun of in the Bulwer-Lytton contest. “His failing metabolism slid further along the steep, declining gradients of encroaching mortality”…he grew old, in other words.

But it also suffers from “not enough.” Despite the purple prose, Metal Sushi feels cold, with not enough energy or passion. It lays out thousands of ideas, but often to little effect. At times it reads like an author writing sentences around interesting words he found in a thesaurus (“A numinous parallax whose focal apex is rooted deep in the reptilian matrix of avatistic consciousness”) – and Michael Gira and James Havoc play that game much better.

But to be honest, I knew what I was getting into. “Black Static” and “Manta Red” were very memorable, but then one has to ask what they were memorable for. David Conway’s writing is a fragmentation bomb of words, blasting you with sensations and ideas, but at the same time blasting other ideas ineffectively away from you. It’s not focused. This is the kind of book that tries to do everything at once, and cram Lovecraft and Akira and Burroughs and Blade Runner into one book. Does it work? Not always. In fact, not even often.

At first, I thought the title was nonsense. Now I see that I was wrong – this book is exactly like metal sushi. Different. Not much nutritional value. Likely to give you tetanus. But eating (or reading) it will be an experience you’ll remember for a while, and I think that was the author’s main intention.

Filed under the bookstore section called “Lifestyles of the Rich and Blameless”, this is the KISS drummer’s attempt to set the record crooked. The KISS breakup soap opera has no shortage of pointing fingers, but Peter Criss adds all eight of his own, plus two (non-opposable?) pointing thumbs, and a pointing toe. Gene’s an asshole, Paul’s an asshole, Ace is an asshole, his grandma’s an asshole, the IRS together comprises an asshole…nothing’s ever Criss’s fault, is it? At its best, the book is revealing and honest. Sometimes it’s shallow and manipulative, 384 pages of PR management. And it was ghost-written, which adds another obfuscating layer between the reader and the truth.

Filed under the bookstore section called “Lifestyles of the Rich and Blameless”, this is the KISS drummer’s attempt to set the record crooked. The KISS breakup soap opera has no shortage of pointing fingers, but Peter Criss adds all eight of his own, plus two (non-opposable?) pointing thumbs, and a pointing toe. Gene’s an asshole, Paul’s an asshole, Ace is an asshole, his grandma’s an asshole, the IRS together comprises an asshole…nothing’s ever Criss’s fault, is it? At its best, the book is revealing and honest. Sometimes it’s shallow and manipulative, 384 pages of PR management. And it was ghost-written, which adds another obfuscating layer between the reader and the truth.