I don’t like what HP Lovecraft has become. Read most modern Lovecraft-inspired books, and coinage like “literary strip mining” comes to mind – people insist on demystifying his mysteries, classifying what’s meant to be unclassifiable, and ruining or ignoring what was great about his stories. The Cthulhu Mythos (ew) is now a parody: as dull and overfamiliar as a Marvel comic book character roster. What everyone needs to do to Lovecraft is leave him alone, and stop scribbling graffiti over his tombstone. There’s something about being able to buy Cthulhu plush toys that makes him not seem cool any more.

I don’t like what HP Lovecraft has become. Read most modern Lovecraft-inspired books, and coinage like “literary strip mining” comes to mind – people insist on demystifying his mysteries, classifying what’s meant to be unclassifiable, and ruining or ignoring what was great about his stories. The Cthulhu Mythos (ew) is now a parody: as dull and overfamiliar as a Marvel comic book character roster. What everyone needs to do to Lovecraft is leave him alone, and stop scribbling graffiti over his tombstone. There’s something about being able to buy Cthulhu plush toys that makes him not seem cool any more.

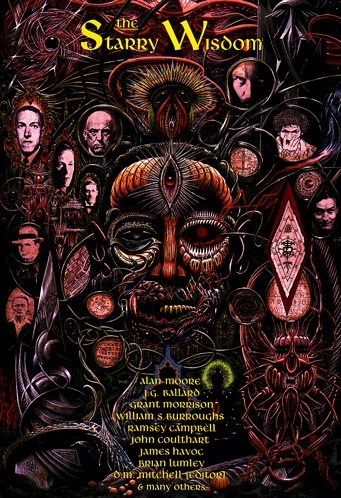

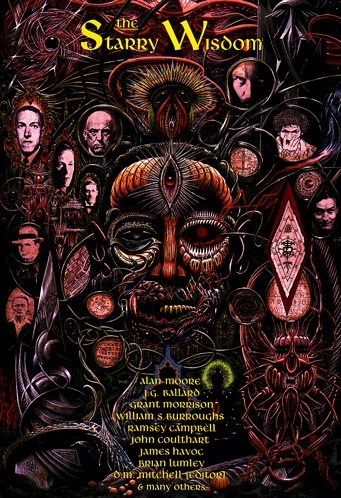

With that said, The Starry Wisdom is a strong collection of stories. It doesn’t take itself seriously, and it doesn’t treat Lovecraft as some kind of holy canon. It contains a lot of tones and moods, a lot of experimentation, and a lot of subject matter that Lovecraft would have been appalled by.

JG Ballard’s “Prisoner of the Coral Deep”, Ramsey Campbell’s “Potential” and John Beal’s “Beyond Reflection” are fairly conservative, but most of the others are full of graphic sex and violence. Some authors take shock value to ludicrous extremes, packing in the sickness and depravity until the stories resemble nasty little transgression piñatas?. Others throw narrative away altogether, and instead try to evoke a strange mood.

Alan Moore contributes three stories – I’m not used to reading him unaccompanied by comic book art. As a stylist he resembles Clive Barker, with a lot of florid, overheated imagery. “The Courtyard” is the best of the three. Michael Gira’s “The Consumer” is a blistering missive written in all caps, reading it feels like being gripped in an enormous fist and shaken. Simon Whitechapel’s “Walpurgisnachtmusik” is intense and strangely synaesthesic – one of the few written stories that I can hear as well as read.

There’s some comix, too. James Havoc contributes “Teenage Timberwolves”, with artist Daniele Sierra backing him up from the shotgun position. Like all of Havoc’s work it manages to be stupid, outrageous, and entertaining. John Coulthart’s famed interpretation of “The Call of Cthulhu” is featured here, but I fear he indulges in some of what I mentioned before, like over-literalisation of Lovecraft’s work. When we actually see Cthulhu, the result is anticlimactic. Someone like Junji Ito would probably have fared better. To be fair, the book is too small to do justice to Coulthart’s art – lines and words pack the pages like sardines in a tin. Creation were many things, but purveyors of impeccable artisanship is not one of them. I seem to recall a certain Suehiro Maruo “artbook” consisting of low-res jpegs copied off the internet…

Some stories hit, other stories miss, there’s a story called “Hypothetical Materfamilias” that misses so hard that it just about circles the world and strikes the target from the other side. Adele Olivia Gladwell was apparently Havoc’s girlfriend, and I hope he got lots of anal in return for this because it’s retarded and annoying and resembles something Burroughs would write if he was twelve years old and in SPED class. Speak of the devil: Burroughs has a story in this book too. When I read his work I always feel like I’m missing a trick – like I’m the mark in some joke or con and he’s laughing at me from the other side of the page. I didn’t understand Naked Lunch and I don’t understand this one, either.

But there are so many stories by so many authors that you’d be hard pressed not to find something you like. Don’t even think of it as being Lovecraft-inspired – the connection is vague and best, and Starry Wisdom is better seen as a collection of extreme/transgressive literature. Lovecraft would have spat venom upon this book, but it works for me.

Something pro-choice people talk about is that pro-life billboards often don’t show the mother’s face, which apparently makes her into an object, or some sort of baby factory. That might be true, but the baby’s face is even less visible. In fact, you can’t see the baby at all. It’s hidden.

Something pro-choice people talk about is that pro-life billboards often don’t show the mother’s face, which apparently makes her into an object, or some sort of baby factory. That might be true, but the baby’s face is even less visible. In fact, you can’t see the baby at all. It’s hidden.

Once, art was like that. You only got to see the end result – the laborious and painful creation process was hidden from public view. A project was announced, and then you’d have no idea of how it was going. Maybe the creator was having the time of his life, or was reaching for the shotgun, or was farming the project off on to an unpaid and uncredited assistant. You didn’t know.

The internet in general and the webcomic in particular changed that. People would upload comics sequentially, page by page. If a update was late, you might get an apology and an explanation why. A bit destructive to the artist’s mystique, but it was interesting. Like if pregnant women had transparent stomachs and you could see the fetus twist and writhe and struggle.

The Blackblood Alliance was a webcomic I liked when my age was less than it is now (tautology). It was a story about talking wolves, with lots of action, and art heavily inspired by The Lion King and Balto. It was familiar and safe, but good for what it was. The creator, Kay Fedewa, would upload pages and talk about them and redraw them as her skills became better.

Unfortunately, not all pregnancies result in a birth. This one ended in a miscarriage. The first issue was completed, and then updates became less frequent, and then stopped altogether. From time to time Kay would announce on DeviantArt that she had turned a corner, was resuming work on the comic, was more inspired than ever, etc. Nothing happened. I heard rumors of personal trouble: the death of a mother. Either way, it was clear that Kay was no longer capable of finishing The Blackblood Alliance.

Maybe she aimed too high. She had big plans for the Blackblood Alliance, such as an MMORPG and a cartoon series. Maybe when those things failed, they took the comic down with them. I don’t know. I got to see part of the comic’s creation, but the really crucial parts remained close to me. Eventually she admitted defeat and handed the comic over to partner Erin Siegel, who has done a whole lot of nothing with it. I wonder if both Kay and Erin regard The Blackblood Alliance as something they did when they were kids – what excites you now won’t excite you forever. Mario Puzo actually wanted to write another book instead of the Godfather. When questioned about it years later, he said “subject matter rots like everything else.”

The fragmentary first issue of The Blackblood Alliance still exists online. Has the rest of it rotted in Kay’s head? Maybe. But that to me makes it really special – probably more special than if the comic had been completed. It’s forever a question mark, forever a mystery. The story is stuck in limbo: it hasn’t ended, and it never will. The internet was the way Kay chose to distribute the comic, but ultimately all it did was show readers exactly how a comic can wither and die on the vine.

McCartney wrote to Lennon “You took your lucky break and broke it in two”. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo takes its lucky break and breaks it into at least three or four. It starts out as an exciting story about journalism, white-collar crime, and ethics, and ends up trying to be American Psycho. The sleazy human interest elements ruin the story, which was a shame, because the story was great. Never have I seen a book so in flight from its strengths.

McCartney wrote to Lennon “You took your lucky break and broke it in two”. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo takes its lucky break and breaks it into at least three or four. It starts out as an exciting story about journalism, white-collar crime, and ethics, and ends up trying to be American Psycho. The sleazy human interest elements ruin the story, which was a shame, because the story was great. Never have I seen a book so in flight from its strengths.

The story is about journalist Mikael Blomkvist, who has just lost a libel suit against a crooked industrialist. With his professional reputation in tatters, and a prison stint looming, he accepts a strange proposal. Forty years ago, the daughter of a legendary Swedish businessman went missing, and a member of the family might be guilty of her murder. Blomkvist must investigate the massive Vanger clan, and try to warm up a case so cold that it’s covered in permafrost.

“Businessman” is one of fiction’s ubiquitous code words. In a porno, it means you don’t satisfy your wife. In a family film, it means you’re a type-A workaholic who forgets his son’s birthday. In a Michael Moore film, it means you’re an amoral monster who probably belongs in a room with padded walls. Stieg Larsson takes no half measures, and provides us with a few businessmen of each description. Some of the Vanger family are nasty, which is troubling. Some of them seem nice – which is even more troubling, because they wouldn’t be in a book like this if they were nice.

The Girl in the title is Lisbeth Salander, a computer hacker. She’s an interesting and marketable character, but the book gives her little to do. She commits a few computer crimes and gets even with a rapist. This is mostly Blomkvist’s show, as the strange story of the Vanger clan uncoils like a snake in the grass. Each discovery raises new questions, and new dangers – some people aren’t happy to have a disgraced journalist rattling the local skeletons.

The book was fine up until this point, and then all manner of fecal products started hitting all manner of spinning blades. There’s a sudden and implausible serial killer plotline, and a Saw-esque torture dungeon…all I could think of was “what?” I don’t have an issue with anything in the book for it is, but they make no sense with what went before. Part of what I liked about Dragon Tattoo was its grounding in reality, and suddenly all of that was yanked away. The sudden twists and turns into B-movie gore porn only succeeded in giving me whiplash.

American Psycho worked at a certain level, but that was because you make concessions to it (it’s a heavily stylised book, it’s metaphorical, it’s told by an unreliable narrator.) Put elements of its plot in a John Grisham book and they’d just seem unbelievable and ridiculous. A book has to have a certain internal logic, an unspoken agreement of what can happen and what can’t. All Dragon Tattoo does is succeed in being a malformed literary chimaera.

The final pages just screw things up even more, with characters taking visits to Australia (??), while the reader gets bodyslammed with plot twist after implausible plot twist. The result is a huge, overstuffed, unconvincing mess: too many reveals, too many changes of motivation, too many themes, too many characters, and not enough sanity. Reading Dragon Tattoo is like going for a car ride and finding that your destination is a beach, an amusement park, and a zoo all rolled into one – with the rollercoaster awash in seawater and tigers climbing the Ferris Wheel.

I don’t like what HP Lovecraft has become. Read most modern Lovecraft-inspired books, and coinage like “literary strip mining” comes to mind – people insist on demystifying his mysteries, classifying what’s meant to be unclassifiable, and ruining or ignoring what was great about his stories. The Cthulhu Mythos (ew) is now a parody: as dull and overfamiliar as a Marvel comic book character roster. What everyone needs to do to Lovecraft is leave him alone, and stop scribbling graffiti over his tombstone. There’s something about being able to buy Cthulhu plush toys that makes him not seem cool any more.

I don’t like what HP Lovecraft has become. Read most modern Lovecraft-inspired books, and coinage like “literary strip mining” comes to mind – people insist on demystifying his mysteries, classifying what’s meant to be unclassifiable, and ruining or ignoring what was great about his stories. The Cthulhu Mythos (ew) is now a parody: as dull and overfamiliar as a Marvel comic book character roster. What everyone needs to do to Lovecraft is leave him alone, and stop scribbling graffiti over his tombstone. There’s something about being able to buy Cthulhu plush toys that makes him not seem cool any more.