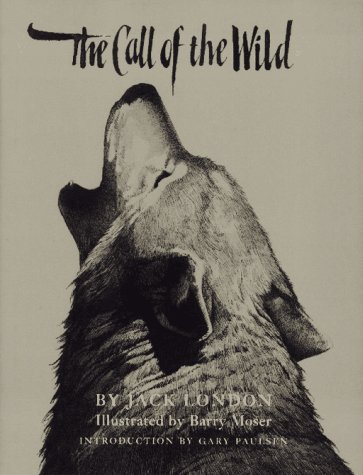

Jack London wrote two books about wolves, and they are the mirror image of each other. White Fang is about a wild animal becoming tame, Call of the Wild is about a tame animal becoming wild.

Jack London wrote two books about wolves, and they are the mirror image of each other. White Fang is about a wild animal becoming tame, Call of the Wild is about a tame animal becoming wild.

Both books are excellent to the point where they are hazardous to have lying around the house. To this day if I see either White Fang or Call of the Wild, I drop what I’m doing, pick it up, and then read through ten or fifty or a hundred pages, caught up once more in the story. These books are hijackers of the brain, and obviously I now keep them far from view.

White Fang is longer and more elaborate, but Call of the Wild is better. It’s spare and lean, like the animals in it, and is paced faster than a modern thriller novel. It’s about a dog named Buck. His upbringing is described in a few pages. Through a stroke of ill fortune, he has found himself on a train bound for the Klondike gold rush, where they need strong dogs with thick coats. Buck’s new home is inhospitable, and it seems he must survive or die. He ends up doing a third thing: transcend.

Books and movies about animals tend to raise public interest in owning said animal as a pet. When Balto come out, children pestered their parents for a pet husky, and no doubt a few unwitting people signed on to become owners of an energetic, destructive animal that needs constant attention and exercise. I don’t think this book would contribute to that problem. Although Jack London often depicts wolves and dogs as noble and romantic, he shows their unpleasant side too. Lex talionis is the order of the day here. Buck is nominally part of a team, but status is everything and he must always be on guard against a sledmate’s fangs in his flank.

There’s not a boring page in the book, from the battles with arch-rival Spitz to mesmerising journeys into the unknown to humorous scenes involving humans. At some point Buck and his team are sold to a trio of comically inept Southerners. Well, it’s only comical at the beginning. Soon dogs start dying under their care, and the laughs stop coming.

Although his creatures are anthropomorphised to a degree, London had a talent in invoking one’s sympathy for animals. The dog Dave is a great example. I was always amazed that London could make me emotionally involved in his plight of a character that doesn’t get a line of dialogue, and only a single identifiable trait (he’s a bit like Boxer in Orwell’s Animal Farm).

The events of the final few pages happen in a blur, and then Buck embraces his destiny. His fate may not seem realistic, but that may be our pitiful prefrontal cortexes talking. Call of the Wild is a book about the deceptiveness of evolution. There’s no “advanced” or “less advanced” in the natural kingdom, and our civilisation just represents a series of adaptations that have proven useful in certain circumstances. Buck adapts in a totally different direction: his environment calls for him to become a primitive creature, and so he becomes a primitive creature. No human in reality or fiction could do what Buck does. We just aren’t wild enough.

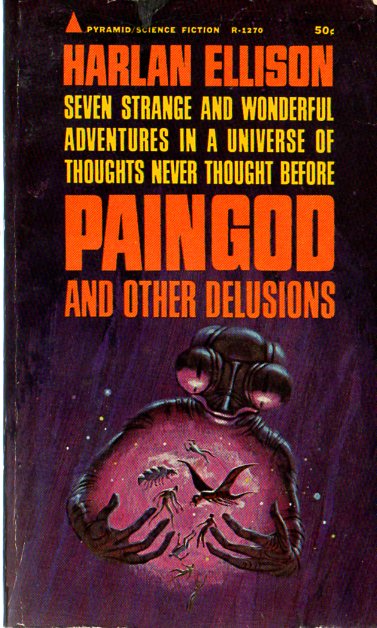

Let’s just say it, Harlan Ellison is not the finest specimen the human race has produced. He probably wouldn’t be in the top 10, either. Ordinarily I’d just ignore his personality and read his stories, like I try to do with everyone else. Three rules for happiness and inner peace: don’t research the personal life of your favourite author, don’t research the meaning of your favourite song, and don’t read the ingredients on your favourite prepackaged snack.

Let’s just say it, Harlan Ellison is not the finest specimen the human race has produced. He probably wouldn’t be in the top 10, either. Ordinarily I’d just ignore his personality and read his stories, like I try to do with everyone else. Three rules for happiness and inner peace: don’t research the personal life of your favourite author, don’t research the meaning of your favourite song, and don’t read the ingredients on your favourite prepackaged snack.

But Ellison makes it difficult, because his egomaniac personality intrudes into the books. You get the impression that he doesn’t enjoy telling stories so much as he enjoys being a man who tells stories. He opens the book with two introductions, and then a foreword for each of the eight stories. Ellison interrupts your reading experience to talk about himself ten times. Nobody give this man a Broadway show, or he’ll spend three hours taking bows under the stage lights.

The quality of the stories is a bit up and down, although mostly up. “Paingod” is not a great story, but it is an interesting one. It’s about a godlike being called Trente whose sole purpose is to apportion and distribute suffering throughout the universe. Spending your life making people unhappy is not good for one’s self esteem, and there’s a lot of navel-gazing philosophy, and rumination on things like duty and obedience.

“‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” is an industrious packmule of a story, carrying a lot of ideas and themes despite its short length. It sports one of fiction’s odder revolutionaries: a perpetual slacker in a world where the greatest crime is to be late. Ellison writes the hell out of this one. I was sad when it was over.

“Sleeping Dogs” is about a government intermediary having to work with a shoot-first-ask-questions-never general who has just committed genocide on an alien world. Ellison lays on the melodrama pretty thick, and the effect is over the top. Ellison seems concerned that we don’t get the point, and he repeats it so many times that soon we don’t want to get the point.

“Deeper than Darkness” is King’s Firestarter written 15 years before. A lonely drifter can create fires with his mind, and earns the interest of government spooks looking to use him as a weapon. Another story with sad violins playing throughout, but I like it more than “Sleeping Dogs.”

Ellison’s short stories are consistently better than his longer works, and his short short stories are better than his longer short stories. I come to this impression from this volume and the few others I’ve read: that he’s at his best when he keeps things brief. Sometimes the longer he goes, the less he says.

But it seems to be quite rare for Ellison to write something that’s a complete waste of time. Even his worst works seem like good ideas marred by horrible writing or stupid decisions, not irredeemable trash. I don’t really get an inner “why does this exist?” reaction from many of Ellison’s stories, and that’s certainly impressive.

Norwegian Wood is a slow book with only a little story, but I did not want it to be faster and I did not want there to be more. Someone once said that being a writer is like being a paleontologist digging up a dinosaur skeleton – and praying you don’t break anything as you transfer it from idea to paper. This book constitutes perfect paleontology. Few books are as precise and well realised.

Norwegian Wood is a slow book with only a little story, but I did not want it to be faster and I did not want there to be more. Someone once said that being a writer is like being a paleontologist digging up a dinosaur skeleton – and praying you don’t break anything as you transfer it from idea to paper. This book constitutes perfect paleontology. Few books are as precise and well realised.

However, parts of the Norwegian Wood skeleton are still underground. Even at the end there questions unanswered, and reasons and whyfors unexplained. Murakami must have decided that they were better off as secrets in the earth. What’s left is an understated but moving story of a young man courting a young woman in 1960s Japan. It’s a fiction book, but one feels justified in thinking that Murakami is transcribing some of his own experiences – he was a college student in Tokyo through this period.

Norwegian Wood has lots of exciting and dramatic and funny moments, all of them written in Murakami’s trademark understated style. Some writers leap and cavort for your attention. Murakami assumes he already has it. Some parts of the book feel real enough to make you uncomfortable. At his best moments, Murakami connects with the reader and makes him feel like he’s actually experiencing a love story, not just reading one.

The characters seem simultaneously realistic and exaggerated, from the disturbed Naoko to the charismatic Nagasawa to the friendly but unknowable Kizuki, whose death is the catalyst for most of the events in the book. They come across as types, but also as people. Main character Toru Watanabe is rudderless and confused, as many young people are, but he’s not uncaring. In fact, he cares too much. Away at college, away from his troubled girlfriend, he starts to feel attraction for another girl. This love triangle forces to make a choice, but that choice merely deepens problems and adds more responsibility to this young man. But that’s the way of things. Choices multiply into more choices, until eventually you’re middle aged and wondering what happened.

Norwegian Wood is a love story, but Murakami sublets narrative space to lots of other ideas. He gets in some shots at student activists, who want to overthrow the system until they graduate and need the system to supply them with a job. He gives Toru a funny roommate who is so likeable that I was saddened when he disappeared from the story. Music is often a prominent feature of this writer’s books, and you could put together a pretty comprehensive 60s compilation album from songs mentioned in Norwegian Wood.

Ultimately, you could view Norwegian story as a symbolic tale of a man facing two paths…and two girls. One is his past, the other his future. The ending is cruel for everyone involved, especially the reader, as he is cut out of one crucial piece of information about what happens to Toru.

But again, that follows from life. We can roll the dice and make decisions…and never know whether we chose correctly or not. I like Norwegian Wood a lot, maybe because it feels like I’m reading about myself.

Jack London wrote two books about wolves, and they are the mirror image of each other. White Fang is about a wild animal becoming tame, Call of the Wild is about a tame animal becoming wild.

Jack London wrote two books about wolves, and they are the mirror image of each other. White Fang is about a wild animal becoming tame, Call of the Wild is about a tame animal becoming wild.