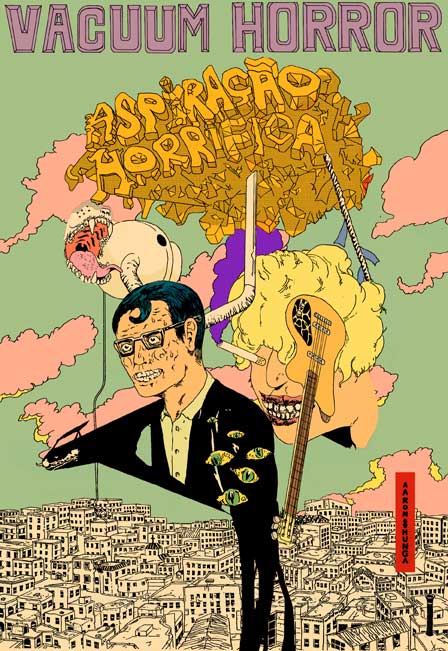

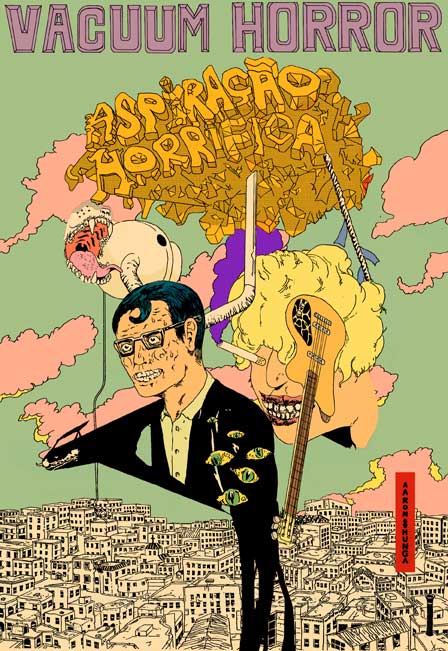

If you are a weird comic junkie, comic artist Aaron $hunga is your connection. With Vacuum Horror, he has released not just a weird thing, but perhaps THE weird thing. The Ur-Weird Thing.

If you are a weird comic junkie, comic artist Aaron $hunga is your connection. With Vacuum Horror, he has released not just a weird thing, but perhaps THE weird thing. The Ur-Weird Thing.

Vacuum Horror (originally a webcomic, now in print) is a unique tale of the end of the world, with humanity going down in a way so ridiculous that it crosses hemispheres and becomes disturbing again.

The story opens with a news announcement. The President has declared that all laws are repealed; America is now an anarchy. The nation immediately collapses into a shitheap of murder, rape, depredation, and fist-pumping Ayn Rand fans. As Lily and her family stock up on guns to protect themselves from marauders (and each other), a discovery is made: their vacuum cleaner can talk.

Vacuum cleaners are not just handy household cleaning devices: They are a race of super-advanced aliens. For years, they have watched us grow strong…and now, we’re too strong. Soon we will be waging genocidal wars throughout the galaxy. There is only one solution: we must be destroyed. We are the dirt of Planet Earth, and the vacuum cleaners must perform their duty.

Lily’s vacuum cleaner, however, has fallen in love with her, and wishes to save her from her fate. Time is running out. Even now, a giant vacuum cleaner is flying through space, and when it arrives, it will suck up every human on Earth.

This sets off an absurd road trip through a Mad Max-esque version of America, as Lily and her vacuum cleaner attempt to meet the vacuum high command to plead for her life. Aaron wimps out on drawing a human/vacuum cleaner sex scene but there’s lots of other funny and grotesque events in his book.

Aaron’s style is nice and very memorable, reminding of Terry Gilliams, Klasky Csupo, Shintaro Kago, and Superjail. It’s rough and abstract, but pernickety and full of details. He loves symbolism, and is fascinated by things, not as they are, but by what they represent.

As an example, when it is necessary for the President of the United States to appear, it is not Bush/Obama but Abe Lincoln, who, of course, is America’s definitive President. Aaron says he used Lincoln because he’s “a letter in a nationalistic alphabet.” In other words, when you need a president, you use Abe Lincoln.

Very odd and amusing, Vacuum Horror is both a weird piece of art and a cohesive and well-thought out comic. Even though Vacuum Horror’s influences are clear, as a product there’s not much you can compare it to.

The story ends the way all great literature should end: with Lincoln’s decapitated head floating through space. Please acquire Vacuum Horror by any means necessary.

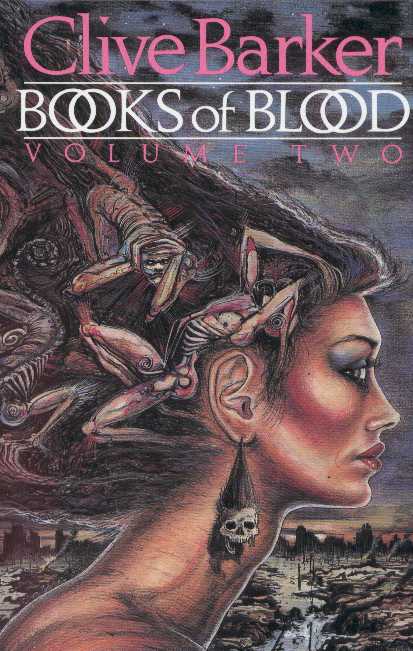

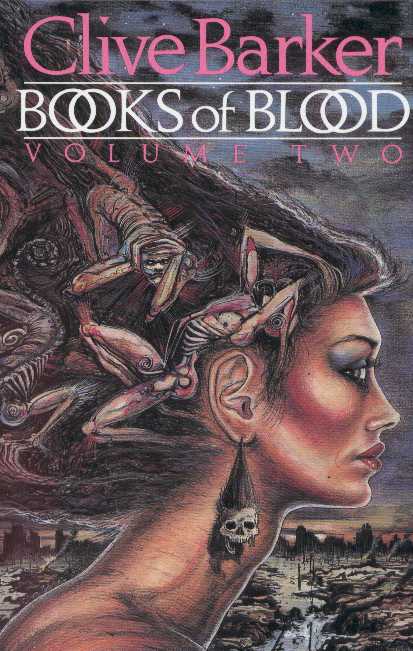

Poor marksmen have the option of firing lots of bullets and letting probability hit the target for them. This was Clive Barker’s approach in his Books of Blood series, and in volume 2 he scored a massive hit.

Poor marksmen have the option of firing lots of bullets and letting probability hit the target for them. This was Clive Barker’s approach in his Books of Blood series, and in volume 2 he scored a massive hit.

“Dread” is Clive Barker’s all-time best anything and one of the scariest horror stories I’ve read so far. A young college student called Steve comes under the aegis of an older man called Quaid, who seems to worship fear as a religion, albeit one that admits no salvation. Quaid is curious about the nature of his god, and wants to use Steve’s brain as a testing ground. The result is a shocking and fascinating story that puts King’s “Apt Pupil” on notice for the most disturbing mentor/student relationship in fiction, despite its short length.

It could have stood to be a bit shorter. The ending of “Dread” disappoints the same way “The Hellbound Heart”‘s did. Clive Barker’s endings are usually too cheap and too camp, and out of phase with the rest of the story. After scenes of powerful existential dread, it’s boring to end with horror movie gore. Welcome to Le Restaurant De Barker, where we serve world-class cordon bleu with pop tarts for dessert.

The other four stories are another day at the office. “Hell’s Event” is about a demon who enters a footrace. Barker does the best he can with an uninspired idea. “Jacqueline Ess: Her Will And Testament” is nice and gory, and evokes more flavours of Stephen King. A woman with psychic powers reshapes her life using the power of her mind, and not in a way endorsed by Oprah or Tony Robbins.

“The Skins of the Fathers” gets silly in places, reminding of Barker’s most annoying creation (Mister B Gone), but keeps lots of action and excitement in the mix and ends up being the most accessible story of the volume. “New Murders in the Rue Morgue” is a stat-flipped “Hell’s Event”, featuring a great idea (C. Auguste Dupin was a real person, Poe’s stories about him weren’t fictional, there’s been a coverup, etc…) but the story is just not that exciting. It seems perpetually ready to kick into high gear…and then you turn the last page and wonder what happened.

The Books of Blood contain about thirty stories in all. None of them reach the high water mark of “Dread” (“How Spoilers Bleed” is close), but there’s a lot of good material spread throughout. But Clive Barker’s inconsistency wears on you. You get good stories, and bad stories. Even worse, you get semi-good stories weighed down by cancerous tumors: poorly-attempted comedy, bad horror movie cliches, incomprehensible “what?” moments that disrupt the atmosphere and jerk you out of story, and stories that seem promising but just can’t get off the runway.

Unreliability is a sin that only artists can get away with this. Imagine being a plumber and only knowing how to replace an S-bend every second day on the job. In a way, the shakiness of the Books is emphasised by their own pull-quote: “Every body is a book of blood; Wherever we’re opened, we’re red.” Crazy, world-bending horror, and they’re heralded by that dumb joke we got tired of in middle school.

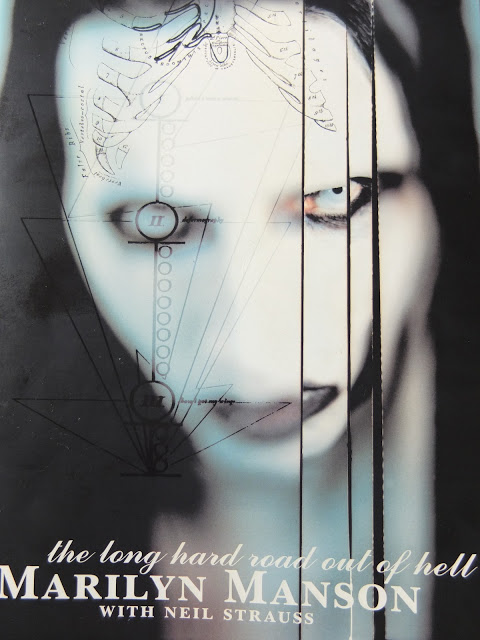

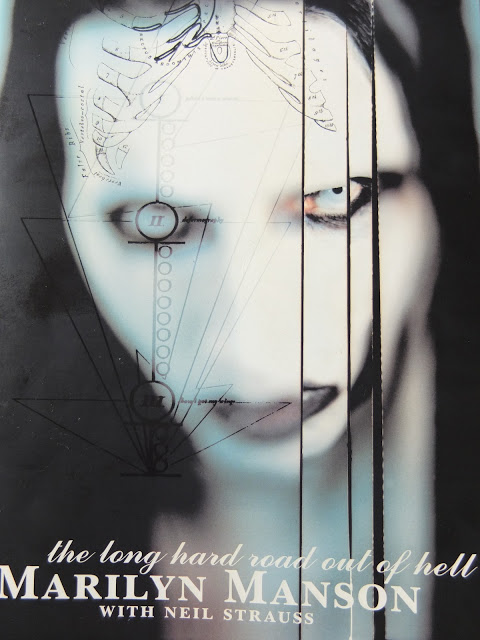

It is generally agreed that Marilyn Manson’s phenomenon is more interesting than Marilyn Manson’s music. If you yourself agree, you may want to read this book, which is all phenomenon and zero music.

It is generally agreed that Marilyn Manson’s phenomenon is more interesting than Marilyn Manson’s music. If you yourself agree, you may want to read this book, which is all phenomenon and zero music.

Published in 1998, shortly before the release of Mechanical Animals, it tells the story of a young boy called Brian Warner, who escaped a childhood of decorum and religion, embraced drugs and satanism, and — after a failed writing career — found his true calling in music (to torture a Clive Barker quote, writing is masturbation, while playing in a band is an orgy). Somewhere along the way he has an epiphany: there there were worse things than being rejected by the cool kids. Being accepted by the cool kids, perhaps. Like Antichrist Superstar, this book has three parts, and with the final part documenting the aforementioned album’s creation and the beginnings of nationwide controversy.

I don’t hate Manson, but I don’t pity him, either. Yes, he was subject to many defamatory attacks, and he was blamed for many things that weren’t his fault…but he has profited handsomely from the controversy, too. He sure as fuck didn’t become the most famous rockstar in America because his music was good.

The book was co-written with Neil Strauss, who is a talented writer — relentless at paring away the rind and getting straight to the interesting parts. If Strauss was a DVD player he’d skip over the movie’s opening credits, start you in the middle of the first action scene, and fast forward through all the dialogue at 3x speed. Reading his books can be exhausting because he throws so much stuff at you so quickly.

The book is full of interesting moments — Brian describes his run-ins with police, his meeting with Anton Szander LaVey, and provides some affidavits from the American Family Association that make him sound like the worst monster of the 21st century (I’m sure he appreciates this very much). I wish there had been fewer random groupie sex stories, and more about Trent Reznor. For a while it seems the working relationship between the two men is building to something big, but the expected payoff doesn’t occur.

The book finds time for lots of philosophising. The revelation Manson has is that nobody is pure, and that it’s all a charade. The Holy Hannah schoolteacher who kept softcore erotica books in her desk drawer. The much loved uncle who had a huge collection of bestiality porn. Everybody has skeletons in their closet. You will think of the verse from the Bible that talks about tombs: beautiful and whitewashed from the outside, dark and seething with corruption on the inside.

Manson has no filter. He talks shit about records labels, old bandmates, current bandmates, and, most of all, himself. His honesty is appealing. Whether he’s poking fun at Daisy Berkowitz’s stupidity (“hey, this album’s about Jesus going on a rock tour, right?”), or outlining his attempt at murdering at ex-girlfriend, he is always direct and blunt. Despite the outlandish content of Hell, it seems more trustworthy than many biographies I read. If this is the expurgated and censored version of Manson’s life, then I don’t want to know about the things that were left out. Manson has always had things to say, but usually those things dance an awkward two-step to (and with) musical accompaniment. Now, the message is unfettered and free.

If you are a weird comic junkie, comic artist Aaron $hunga is your connection. With Vacuum Horror, he has released not just a weird thing, but perhaps THE weird thing. The Ur-Weird Thing.

If you are a weird comic junkie, comic artist Aaron $hunga is your connection. With Vacuum Horror, he has released not just a weird thing, but perhaps THE weird thing. The Ur-Weird Thing.