Yay, twelve Junji Ito one-shot stories. This format is where Ito is most comfortable. His style is visceral and intense and works best in small doses. Also, it’s hard to care about slightly flat characters when you only spend 20-30 pages with them.

Yay, twelve Junji Ito one-shot stories. This format is where Ito is most comfortable. His style is visceral and intense and works best in small doses. Also, it’s hard to care about slightly flat characters when you only spend 20-30 pages with them.

Ito loots ideas from all manner of places: childhood phobias, ancient myths, Lovecraftian existential terror. There’s no unified theme running through these stories, except perhaps that you should be careful picking up rocks. No matter how safe and familiar a rock might look, there’s always something squirmy and chitinous and unpleasant on the damp side.

“The Bully” is one of Ito’s most frightening tales. No gore, nothing supernatural, just a really powerful psychological tale of childhood trauma following two people long after they’ve grown up and left the schoolyard behind them. It doesn’t matter that we never find out what happened to the woman’s husband. The consequences of his disappearance are enough. “The Devil’s Logic” is equally powerful. A girl climbs to the top of a school building and throws herself to her death, and only one of her classmates knows the reason why. Ito is just on fire in these two stories.

“A Deserter in the House” is pretty fun. A WWII-era Japanese family is harbouring an army deserter in their basement. Since he never leaves the house, they fuck with him by feeding him all sorts of fake news about the war (Japan is winning the war, America is on the verge of surrender, etc…). This is about as good as you get character-wise with Ito. The family is a diverse cast with some understandable (if cruel) motives, and we’re not sure whether to pity or hate the deserter. Unfortunately, Ito wraps up the story on a dull note. I wish it had ended as well as it started.

“Den of the Sleep Demon” is a vile retelling of Jekyll and Hyde, featuring a man with a hellish force of evil inside him (literally inside him), and a girlfriend who helps him fight back. “Love as Scripted” is also very cool. A girl dates an actor, and finds that she likes his stage presence far more than the real thing. It raises the interesting question of whether love for something fake (whether it’s a fictional character, or a real person putting on a fake persona) is any more or less valuable than love for the real thing.

A handful of stories fall short of the mark. “Sword of the Reanimator” is shitty shonen fluff featuring magic swords, ancient legacies, epic boss battles, and all the rest. I have no idea why Ito wrote this story, it’s just inexplicable and awful. Probably his editor made him do it. “The Face Burgler” is about a high school girl who steals other girls’ faces, and is over-long, and too similar to Tomie.

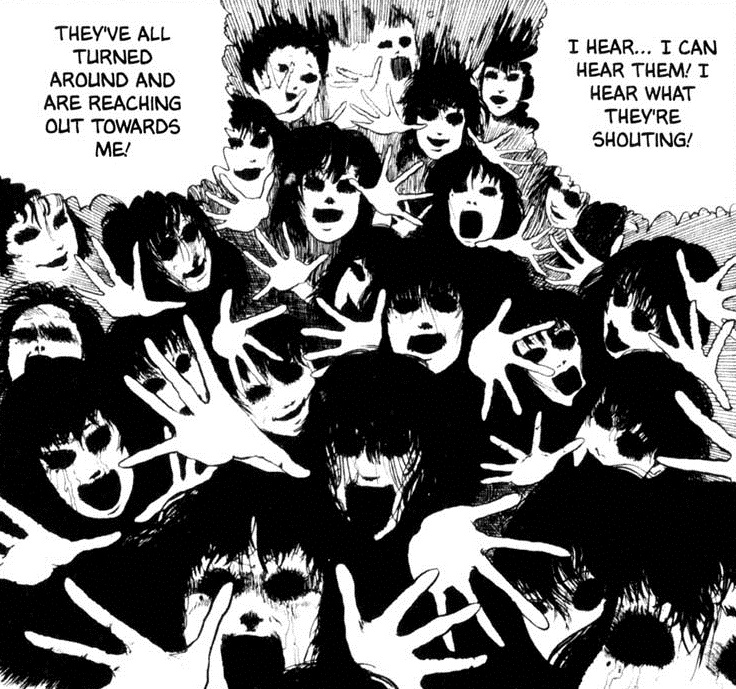

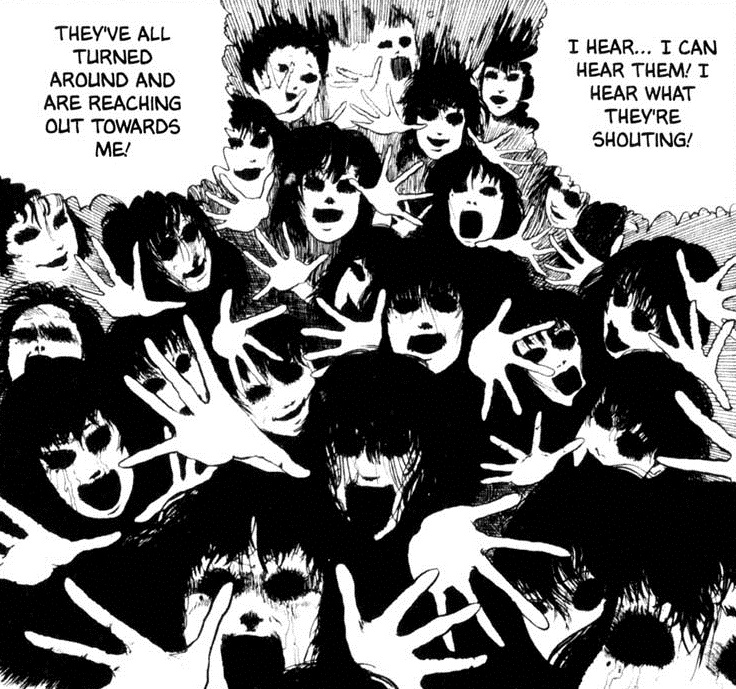

“Village of the Sirens” is big and ambitious, and reads almost like an early test run of Uzumaki. It has its moments but I think he ran out of pages, because the drawings are crowded as hell and he’s clearly rushing the plot along at a million miles an hour. When you have a demon as big as a skyscraper rising from a black pit, doesn’t that warrant a full page drawing or a two page spread instead of a series of tiny cramped little panels? I think if the story had been allowed to breath more, it would have been better. “Unbearable Maze” is like queuing for a ride at a carnival only to be told the ride’s out of order. It has the most unsatisfying ending imaginable.

My favourite story from the volume? “Bio House”. It’s Ito’s second story ever (after “Tomie”) and although it’s stupid and plotless, it’s also outrageous and entertaining. I can’t explain why I like it so much. When Hideshi Hino draws these sorts of stories I hate them.

Although there are ten Museum of Terror volumes, this is likely the last one we’ll see officially released in English. Many of the stories in subsequent volumes have been scanlated, but Dark Horse’s MoT editions frankly rule and it’s a shame there will be no more of them.

This second volume of the MoT series contains another set of Tomie stories, mostly from the later part of Junji Ito’s career. They’re consistently better than the ones from volume 1. A lot of the early Tomie stories suffered a bit from Ito’s inexperience. These stories (especially the later ones) are more like what Tomie should have been from the start: short, punchy horror stories full of imagination and atmosphere.

This second volume of the MoT series contains another set of Tomie stories, mostly from the later part of Junji Ito’s career. They’re consistently better than the ones from volume 1. A lot of the early Tomie stories suffered a bit from Ito’s inexperience. These stories (especially the later ones) are more like what Tomie should have been from the start: short, punchy horror stories full of imagination and atmosphere.

“Little Finger” strikes a graceful trifecta of funny, scary, and sad. An orphan chops off the fingers from one of Tomie’s hands…and they grow into four separate Tomies! Pinky Tomie is badly scarred and gets bullied by the other three fingers. The orphan (who is very ugly himself) takes care of her and nurses her back to health, only to be repaid in a typical Tomie-esque fashion.

“Boy” is very unpleasant, and touches upon a theme of youth delinquency. A young boy meets Tomie, and in time is destroyed by her. It reminds me of Ito’s classic tale “The Bully”, in that it’s an almost archetypical story of innocence corrupted.

“Moromi” is 34 pages of sicko shit that makes me feel like I need a shower. Someone murders Tomie, minces her body down to a pulp, and attempts to dispose of her remains by mixing them into a sake brewery. What happens next is implausible and revolting, like all the best Ito stories. The final page is one of those brilliant artistic flourishes that only Ito knows how to do.

“Babysitter” is barely even a Tomie story. A young woman finds herself babysitting a very unusual baby who screams continuously except when she sees fire. Ito is consistently good at making odd premises work, and he more or less delivers the goods here. I wish it had a stronger ending.

“Gathering” is the worst story on here. It’s forty pages of Tomie being an insufferable bitch, and Ito couldn’t figure out how to end this one either, so he just has all the characters kill each other for no reason. Oh well. Can’t win them all.

The final three stories comprise a thrilling three-part tale that is staged the way the Wachowski’s originally planned the Matrix (that is, movie, prequel, sequel). Tomie meets a male model who is as stuck up and vain as her. Their relationship immediately turns sour, and they end up mutilating each other. The male model lacks Tomie’s powers of regeneration, but he is nevertheless a worthy adversary, and faces down against her in many violent escapades. Finally, he realises that Tomie can never be killed, he so attempts to take away the thing she values most: her beauty. His eventual plan is unbelievable in its cruelty. What can I say about the ending to “Old and Ugly”. Is it…good? Bad? I don’t know. My feelings on it keep changing. It certainly made an impression on me that none of the other Tomie stories did.

These are Tomie’s final set of adventures as of this writing, and it’s really interest where Ito took the character. She’s completely evil, but she has a lot of charm…as the men in her stories would agree, I’m sure.

Still, don’t let Tomie be all you read by Junji Ito. As good as they are, these stories are merely the beginning of his catalog.

The Museum of Terror books are collections of Junji Ito’s early manga stories. In 2006, English readers lucked out when Dark Horse started releasing them in English. Unfortunately, the series was cancelled at volume 3 due to lack of sales. Lesson learned: manga fans are the most dedicated and passionate fans on Earth…unless you want to earn money from them. Then you starve to death.

The Museum of Terror books are collections of Junji Ito’s early manga stories. In 2006, English readers lucked out when Dark Horse started releasing them in English. Unfortunately, the series was cancelled at volume 3 due to lack of sales. Lesson learned: manga fans are the most dedicated and passionate fans on Earth…unless you want to earn money from them. Then you starve to death.

The first volume is all about Tomie, who is Ito’s most famous character…a girl who inspires madness and obsession in the men around her, to the point where they try to kill her. They often succeed. But it soon becomes clear that Tomie is not even close to human, and she always comes back.

Apparently she was inspired by an event from Ito’s childhood, when a classmate died in an accident and he wondered how people would react if she showed at up school the next day. The nine 30-40 page stories all hit a similar riff: Tomie appears, guys fall in love with her, guys kill her, and she is reborn.

The Tomie formula soon becomes very familiar…even overfamiliar. Honestly, these are far from Junji Ito’s best works. Tomie launched Ito’s career and paved the way for a lot of great manga, but set against his later material they seem fairly tame and unremarkable. Ito imagination is nearly limitless, and Tomie constrains him.

How so? There’s no sense of mystery about Tomie. We know what her powers are, and what her personality is like, and the effect she has on people around her. We know everything about her, and that’s boring. The crazy off-the-rails madness of Uzumaki makes Tomie look suspiciously like a Dead Teenager movie, where we know all the beats it’s going to hit, and the only question is whether Jennifer Love Hewitt or Sarah Michelle Gellar will survive for the sequel.

…But of course, another difference between Uzumaki and Tomie is that Tomie is creepy undead moe-ish girl and is thus hugely marketable With nine movie adaptations of Tomie to date, Ito’s humble creation has become a horror franchise, questions of quality aside.

Out of these nine stories “Painter” is by the far the best, mostly because of its powerful Gothic atmosphere. All of these stories are violent and intense but some of them are a bit lacklustre in execution, either because of poor art (some of these are Ito’s very first stories) or lackluster plot or execution. “Revenge” is dull, just an uninspired retread of other ideas in the manga. “Mansion” is overkill in the other direction. Ito tried way too hard with this one, it’s one unbelievable and over-the-top plot development after another until eventually I gave up caring.

Yet at the core of the Tomie mythos there is a powerful idea. The stories lean pretty heavily on gore and shocking imagery, but ultimately they’re not about that. They’re not even about Tomie! These stories are about obsession, and how quickly we can slide from being rational human beings to automatons of our primal urges. Tomie might not be interesting. But the insane, obsessed males around her are actually fairly frightening.

Yay, twelve Junji Ito one-shot stories. This format is where Ito is most comfortable. His style is visceral and intense and works best in small doses. Also, it’s hard to care about slightly flat characters when you only spend 20-30 pages with them.

Yay, twelve Junji Ito one-shot stories. This format is where Ito is most comfortable. His style is visceral and intense and works best in small doses. Also, it’s hard to care about slightly flat characters when you only spend 20-30 pages with them.

This second volume of the MoT series contains another set of Tomie stories, mostly from the later part of Junji Ito’s career. They’re consistently better than the ones from volume 1. A lot of the early Tomie stories suffered a bit from Ito’s inexperience. These stories (especially the later ones) are more like what Tomie should have been from the start: short, punchy horror stories full of imagination and atmosphere.

This second volume of the MoT series contains another set of Tomie stories, mostly from the later part of Junji Ito’s career. They’re consistently better than the ones from volume 1. A lot of the early Tomie stories suffered a bit from Ito’s inexperience. These stories (especially the later ones) are more like what Tomie should have been from the start: short, punchy horror stories full of imagination and atmosphere. The Museum of Terror books are collections of Junji Ito’s early manga stories. In 2006, English readers lucked out when Dark Horse started releasing them in English. Unfortunately, the series was cancelled at volume 3 due to lack of sales. Lesson learned: manga fans are the most dedicated and passionate fans on Earth…unless you want to earn money from them. Then you starve to death.

The Museum of Terror books are collections of Junji Ito’s early manga stories. In 2006, English readers lucked out when Dark Horse started releasing them in English. Unfortunately, the series was cancelled at volume 3 due to lack of sales. Lesson learned: manga fans are the most dedicated and passionate fans on Earth…unless you want to earn money from them. Then you starve to death.