Smart and sharp. Fans of shit will want to miss this one, for it is emphatically not shit. Few films draw together such broad influences or mix them so confidently. Neo-western, plus Hitchcock, plus genre UFO flick, plus highbrow Baudrillardian meditation on filmic imagery, plus 90s monster anime, plus what else ya got in the fridge?

Many missed the movie’s theme, which seems straightforward to me.

Nope is about mankind’s desire to control wild things via language, to recontextualize the world of dripping teeth and claws into something safe, something human, something we can control and exploit.

This is illustrated in the movie several times. OJ’s horses are harmless entertainment…until they’re not. Gordy is a funny wacky sitcom monkey (clearly inspired by 1951’s Bedtime for Bonzo)…until he’s not. These are wild animals. The metaphors humanity has recast them in are shallow and easily broken. Savage ancient eyes swivel wildly inside the smiling-face masks. We live around things can kill us. The usual solution (shutting our eyes and wishfully imagining that there aren’t also teeth inside the masks) can turn abruptly fatal.

The film is replete with references to extremely early pre-Hollywood cinema. Another one I thought of is 1903’s Electrocuting an Elephant, which documents the death of Topsy, a Coney Island circus elephant that (lazily quoting Wikipedia) had “killed a drunken spectator the previous year who burnt the tip of her trunk with a lit cigar”. What was going through that man’s head? Maybe he thought he was safe. After all, he’d paid for a ticket. Surely the elephant wouldn’t dare harm a paying customer of the circus.

The deadliest animal in the film is Jupiter, who kicks off everything with his amusement park wheeze (or so it’s implied). But note that he could have justified his actions. He had everything under control, bro! Trust me, bro! Nothing had ever gone wrong before, bro! And don’t you work with animals too, bro? That, again, is applying human logic to an alien world. A wild animal has not signed a contract and it is not bound by any natural law to perform as you expect. A cat will merrily play with you. Then a chance hand movement triggers a sparking cascade of neurons, thousands of years of domesticity crash like invalid code, and it lashes out. In that impulsive moment, it wants to destroy you. It’s only cute because a cat is too small to kill. If it was the size of a tiger, your guts would be outside your body. Nobody who ever picked up a snake thought they would get bitten by it.

A few years ago, I noticed people treating their pets as if they were human. Women would call their dogs “fur babies”. They’d talk to their dog in a coochie-coo baby language, as though their dog was a human infant. And when their pitbull mix attacked someone, they’d react with shock. That’s not how they raised their little guy to behave! Imagining a human face on a strange and alien thing comforts us, and affords us an illusion of control. But wildness still lives underneath, and can bite through that illusion as suddenly and finally as it can bite through you.

Always described in terms like “absurdist nonsense”, Holy Grail is far from nonsensical or absurd. It depicts a rigorous and orderly world. Its has bones of laws and tendons of logic. Yes, the rules it works by often strange and always arbitrary, but the characters are still forced to follow them, even when the rules are abruptly changed, subverted, or exposed as hollow and meaningless.

It’s a funny but sinister movie: characters are trapped in predefined roles and although they show some awareness of their artificial world, it’s a world they can never escape. Arthur, Lancelot, etc are checker pieces in a game that abruptly changes to chess, to parcheesi, to Mahjongg, to Starcraft II. It’s almost as much a dystopian satire as Brazil.

If the movie has a point, it’s this: “the rules we’re made to follow are all-important…until suddenly they don’t exist.” That’s an important idea in much of the Pythons’ work, and here it is the motor of the story. This dyadic structure (rule -> subversion) occurs again and again, almost too many times to count.

The Peasant. King Arthur justifies his reign with a speech about the Lady of the Lake giving him a magic sword. This is punctured by a peasant’s paraphrased observation “…but isn’t that a really stupid way to elect a leader?” King Arthur can’t answer (beyond saying “shut up!”) because the peasant’s obviously right. It is.

The Black Knight. He blocks King Arthur’s path, and ignores a royal order to step aside. Yes, Arthur fights and defeats him, yet in a weird way, this disempowers him as king. He has no authority over the Black Knight, beyond the strength of his sword arm (what would he have done if he was someone who couldn’t fight well, like a dwarf or an old man?). A king shouldn’t have to fight pointless macho duels against random subjects on the road. If he’s reduced to that, his kingship is either false or meaningless.

The Knights of Ni. Arthur goes on a long, frustrating quest to find a shrubbery, only to return and find that the people he was dealing with have disbanded, reformed under a new name, and have no intent of honoring their deal. His quest is rendered useless by bureaucracy, flipping from all important to futile.

The French. French soldiers occupy a castle on British land, and taunt Arthur for his inability to dislodge them. This further deflates his stature, because (as with the Black Knight), his kingship gives him no actual authority. People can insult, mock, or defy him, and he has little recourse except to insult them back or clumsily try to fight them—tactics of commoners, not kings. This scene has happened many times through history. Foreign colonizers arrive, establish an outpost or a trading colony, and because of a technological advantage like cannons or horses, the regional power can’t do anything. This triggers a regional power shift: the subjects learn that their king’s power was illusory. He wasn’t chosen by God, and wasn’t the last in the line of serpent people. He owned the land because he was able to defend it, and once someone with brass cannons came along, he was no longer able to defend it and didn’t own diddly-squat.

The Legendary Beast. At Castle Aarrgh, the knights are chased into a corner by a horrible monster. Things look grim…until the animator drawing the monster dies, and the monster turns into a harmless drawing (which, of course, it always was)

The Bridgekeeper’s Riddles. Knights try to cross a bridge, but are blocked by a bridgekeeper who asks unfair riddles. Several knights fail and are flung to their deaths. But then Arthur lawyers the scenario’s rules against the Bridgekeeper, gets HIM tossed into the pit, and the remaining knights cross with no further problems. This is a rare example of a character actually manipulating the logic of their world in a positive direction (although Arthur seems to have done so by accident).

So that’s the film. “The rules matter…until they don’t.”

If the Pythons have a point, it’s this: most of society’s instructions are arbitrary, and can be ignored. We could all collectively believe Britain is part of France, and it would become part of France. Often, the future belongs to the powerful and clever and mad, because they have the “hacker mindset”—they can stare past something’s surface illusion and discover its underlying interface. You can try to speedrun a game by playing it “properly” (the way the developers intended). But someone else has found a way to glitch through a wall and has already set the Any% WR.

Yes, the average Joe has to follow rules—people with big sticks tend to whack you if you don’t—but you’re a sucker if you actually believe in them. They aren’t real. They are largely made up by people who want to control you. Do not love the law: it does not love you back. Those who wave a rulebook and say “no fair! A dog can’t play baseball!” are fated to watch a dog dunk on them, over and over, forever.

I do not regard this as a nihilistic AJ Soprano film about how nothing matters. Just that our sense of the world’s shape (and of things like morality and ethics) is a judgment we should make ourselves, rather than accepting someone else’s. Viewed this way, it’s strangely ennobling. All chains are glass. We can imagine the world into new shapes.

I saw this as a kid. It enchanted me as few movies have done. I could not predict where it was going. And this gave the story, despite its surface silliness, a deep underlying realism.

At six years of age, I was noticing already that certain things always happened in movies: the good person always won, the bad person always lost, side characters often died, main characters never did, and so on. Next to these obvious commercial formulas, Holy Grail was scary. Unpredictable. It seemed ruthless and mad, the way characters just horribly died, the way the quest just seemed doomed to fail. It was like a snake in my mind for a long time. Forget the surrealist parts. For the first time, I had seen the world I lived in depicted in a movie.

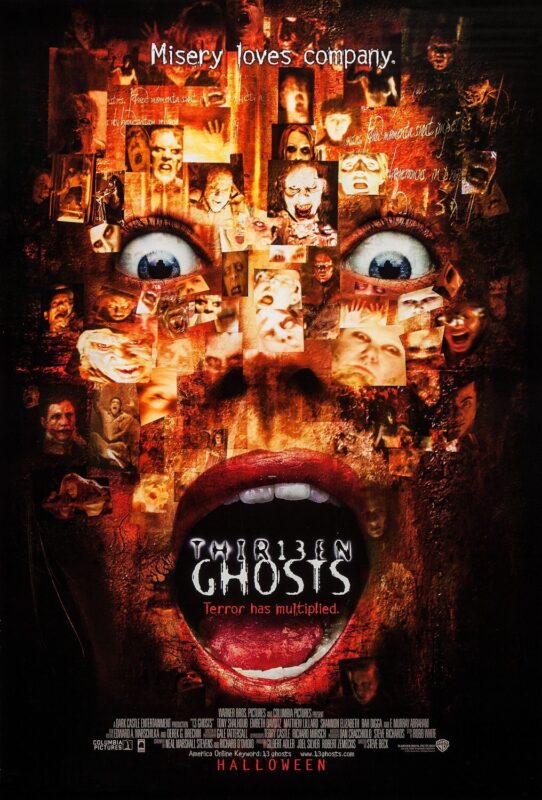

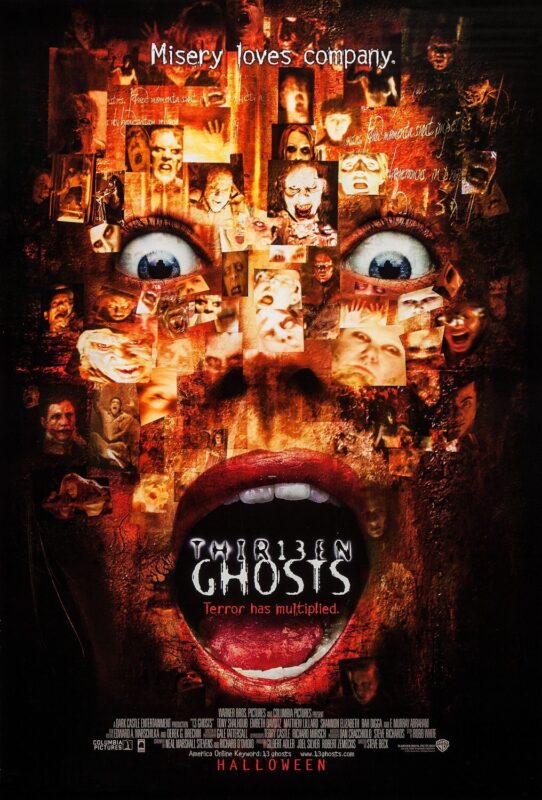

Thir13en Ghosts shows the Dark Castle formula (remaking Fi5ty year old horror movies with Gen X stars and an edgy nu-metal/rap soundtrack) hitting steep diminishing returns on only their Sec2nd film. Hate to see it.

These movies are sort of charming to me now, because they’re wrapped up in era nostalgia. Viewed objectively, they’re very lame and almost pathetic. They obviously started out as a “how do we relate to The Youth of Today?” brainstorming session among extremely middle aged old men, and nearly finish that way, too.

Ninety-n1999ty-nine’s House on Haunted Hill punched a bit above its weight due to good performances and some inspired art direction. It shows the path they could have taken: Vincent Price was forced to gesture toward (and imply) certain topics we can now state plainly and openly, so maybe subtexts of repressed sexual tension and perversion could be explored a bit more.

Yes, there’s only so much mileage to be had in shouting things another movie whispered—eventually more becomes less—but it would have been interesting for the films to really go all out and debauch themselves. Sadly this did not happen. Don’t worry though, Zemeckis and Silver came up with way better ideas, such as “wouldn’t it be funny if Paris Hilton was in a horror movie lol”.

ThirOneThreeEn Ghosts does not particularly punch above its weight and would struggle to KO Glass Joe. There’s no Geoffrey Rush nor Famke Jannsen and nor is there much inspiration. It’s really loud, and seems like a forerunner to the It movies in that I have to watch it with the audio nearly silent and subtitles on otherwise it reduces my eardrums to exploded and atomized dogfood. Also, it has really, really bad acting. Matthew Lillard is actually horrible in the opening scene. It’s several painful minutes of “jeez, was that the best take you got from the guy?”

The plot is farcical. Few movies survive having their plot recapped on Wikipedia but this one sounds particularly like an extended South Park gag. (excerpt: “Kalina explains that the house is a machine powered by captive ghosts, allowing its users to see the past, present, and future. The only way to shut it down is by creating a 13th ghost from a sacrifice of love.”)

Beating up on ThirThirteenEn Ghosts is pointless. This is the offspring you get when Daddy Corporate Balance Sheet and Mommy Corporate Balance Sheet love each other very much. Interesting as a relic from a particular time in horror movies, it’s like a peaceful dinosaur grazing while an asteroid called Saw is streaking down unseen on top of it.