A cloud of iridescent energy slides across the galaxy, destroying all in its path. As it approaches Earth, James Tiberius Kirk bullies Starfleet into giving him control of the Enterprise, one last time. Incidentally, did James go through boot camp? Hard to imagine a guy called Tiberius doing push-ups and getting yelled at by R Lee Ermey. When your name is Tiberius they probably promote you straight to captain.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture is great, if in a troubled way. It’s like a titan, ready to collapse under its own weight. The philosophical method of”structuralism” seeks to understand things through their relationship to other things (eg, a ship’s mast can only exist if there are sails and a hull, otherwise it’s just a wooden pole), and Star Trek: The Bowel Motion Picture can only be understood in light of its own difficult creation.

Let’s start at the beginning. Once, there was a television show called Star Trek. It was both unpopular and cancelled. Half a century later, it’s the defining science fiction series of the silver screen.

How did this reappraisal happen? The same way the Velvet Underground became popular: they sold a few thousand copies, and all of those people started a band. Star Trek’s audience was tiny, but it consisted was of scientists, writers, activists, and other people who wielded a disproportionate impact on the tastes of 1970s America. Their beloved show was dumpstered, but these people were too aggressive to let it be forgotten. They rang phones. They wrote letters. The megaphone-wielding minority soon had the show firmly established in syndication, and a slow critical reassessment began: this thing is actually really good.

Star Trek was often campy, but never cynical or insulting. The writing was often broad, but was never boring. Gene Roddenberry was brilliant at directing attention away from the show’s weaknesses (its budget) and toward its strengths (screenwriting, and Shatner, Nimoy, and Kelley’s acting).

With voltage gathering for a continuation for the series, Paramount Pictures and Roddenberry began working on a pilot. It was a mess. Writers were commissioned, and their scripts rejected. Actors were hired, and their parts written out. Sets were built, then stripped down. I’m stunned that Burbank’s air was declared safe to breathe after so much burnt cash.

Finally, just weeks before shooting was due to start, Close Encounters of the Third Kind hit the box office like a wrecking ball. The prevailing cultural winds now favored movies instead of TV. Paramount panicked and changed their plans: when Star Trek returned, it wouldn’t be as a TV series but a motion picture.

This spelled disaster for Roddenberry. There was not enough time. The production was thrown into chaos, and the planned pilot was hastily refitted into a two hour movie, with a script written as they went along.

The result is a odd experience, stretched and deformed. It’s a Star Trek television episode viewed through a funhouse mirror: you can recognise the shape, but it’s 50% wider than it needs to be. The opening sequence is thrilling: three Klingon ships are evaporated in an impressive visual effects sequence. Exciting. Star Trek was back, now with a budget!

But then we get an hour of “character development”, meaning James T Kirk butts heads against the Enterprise’s dull new captain, while the plot spins its wheels and goes nowhere. We also meet a female alien called Ilya, who talks and talks and talks and sets records for uninspired character design. I’ll buy that a man with pointy ears might be an alien. Ilya’s literally just a woman with a shaven head. You can find plenty of aliens like her at the local slam poetry meet.

The film’s strengths are its visuals: something that was never a strong point with the original show. Douglas Trumbull and a young John Dykstra slather the frame with luminous rainbow hues (Trumbull previously worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the film owes a lot visually to that one, including a “smash cut from rainbow fluorescence to stark white” moment that matches 2001’s Star Gate sequence). The more practical effects are beefed up as well. A tiny Burbank sound stage is make to look like an absolutely massive cargo bay thanks to forced perspective (those tiny figures in the background? Children.) I think this is the first time we’ve seen a Star Trek space battle where both ships are composited into the same frame (as opposed to a shot/reverse shot of the Enterprise firing and another ship blowing up.)

The story is a bit perfunctory, and the imagery seems to transcend the characters until they’re reduced to spectators, gaping at the wonders of the cosmos. Maybe that’s the attitude Star Trek always tried to evoke. More likely, it’s a disguise for the fact that this was supposed to be a TV pilot, and they just plain didn’t have enough story.

I once saw a film called American Movie, about a pair of young indie filmmakers. One of them has a memorable monologue: “There’s no excuses, Paul. No one has ever, ever paid admission to see an excuse. No one has ever faced a black screen that says: ‘Well, if we had these set of circumstances, we would’ve shot this scene… so please forgive us and use your imagination.’ I’ve been to the movies hundreds of times. That’s never occurred.”

He should have seen Star Trek: TMP. It has excuses. Many of the visual effects (although stunning) don’t serve a purpose beyond “we don’t have any actual story to put here, enjoy these flashing abstract colors”. Big chunks of the film are a laser light show in space, intercut with shots of the crew looking awed. For a while, you share their awe. But then it feels like it’s time for something to happen.

Calling a movie “The Motion Picture” sounds either presumptuous of horribly underconfident: you’re either suggesting that it will be the definitive one, or the only one. In the case of ST:TMP, I can’t even call it A Motion Picture, as it’s been recut and re-released many times. The film is now legion, I’m not sure if the original version is exists today in a purchasable form. Although it’s a different sort of Star Trek, I enjoyed it a lot.

(It’s worth noting that Orson Welles voiced the cinematic trailers for this movie. One year later, he’d be voicing Manowar songs, and commercials for frozen peas.)

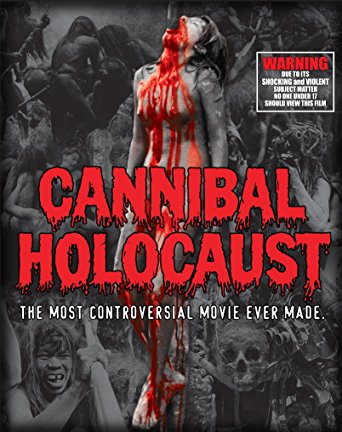

Cannibal Holocaust has many descriptors, but only one matters: filth. People watch it because it’s filth. Midway through, an anthropologist and his guide surreptitiously watch a native ritually rape and sacrifice an adulteress. “Enjoy the show,” his guide advises. The anthropologist throws up, but doesn’t stop watching.

Cannibal Holocaust has many descriptors, but only one matters: filth. People watch it because it’s filth. Midway through, an anthropologist and his guide surreptitiously watch a native ritually rape and sacrifice an adulteress. “Enjoy the show,” his guide advises. The anthropologist throws up, but doesn’t stop watching.

Few films manage to capture such vileness and perversity. The jungle’s heat and humidity seems to press upon you through whatever piece of glass you watch it on. The camera lens itself appears infected, like a petri dish. The soundtrack mixes whimsical Italian pop, eerie tribal percussion, and experimental electronic music, becoming a bleeding and suppurating welt of sound.

The plot is secondary, or tertiary, or duodenary. An anthropologist is in the Amazon, searching for a film crew that went missing many months before. He discovers their tapes, brings them back to civilisation, and watches them. There isn’t much to this movie beyond a powerful impression of sickness. But it’s clever: because it knows to keeps the viewer at arm’s length. Other than one attempt at a moral point (“what if WE’RE the real cannibals?”), the violence happens very far from home, both literally and morally. You don’t feel threatened by the gore and bloodshed, or the fact that you’re enjoying it. It happens in a part of the world so strange that it feels like an alien planet, and everyone who dies is either a primitive native, or a white person who “deserves it” (the missing film crew are established as arrogant and dislikeable). That was Cannibal Holocaust’s “it factor”. Guiltless violence.

There was a “shock jock” radio duo called Opie and Anthony who were famous for their sex-based stunts (such as launching fireworks out of a female fan’s vagina, which sounds very boring over a radio show, but whatever.) At the peak of their infamy, they were interviewed by conservative talk show host Bill O’Reilly. They described their on-air hijinks, and he took them to task, calling them disgusting and degrading to women and so forth. Very well, they’d expected that. They gave him stock answers. Mumble, radio show, mumble, entertainment, mumble, First Amendment. Next question, please.

But O’Reilly wouldn’t let the topic go. He kept coming back to it, over and over, like a dog with a bone. The sex. The nastiness. He wanted to hear all about it. He wanted them to describe it. He wanted to register his shock and disgust, repeatedly. They had an epiphany: O’Reilly was exploiting sex in the exact same way they were. But because his audience was made of grandmas and geezers (median age of Fox News’ primetime audience: 68, according to Nielsen), he had to cloak his pruriance in moral disapproval. It was his way of getting filth on the air: he just had to make sure it was coming from someone other than him, with him wagging a disapproving finger.

Everyone loves perversion, but some of us are hypocrites about it. There’s a saying among prostitutes: he who points with one hand is masturbating with the other.

I won’t overstate Cannibal Holocaust’s cleverness. Of course, “awful things happening in foreign lands” is a common trope, even outside cinema. Octave Mirbeau’s The Torture Garden features long, almost slavering descriptions of the tortures supposedly carried out in Cathay, and George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels work at a similar level (Marquis de Sade, with typical ballsiness, set all of his atrocity porn within his own nation of France). In fact, Cannibal Holocaust’s portrayal of natives will discomfort modern viewers, even beyond any of the events of the film. You’re not supposed to make indiginous peoples look like savages, and monsters. They’re people!

Yes, they’re people. But at real life digging sites, all around the world, anthropologists find human bones in ominous proximity to camfires. Sometimes they’re roasted and split, the marrow sucked out. The events portrayed in the film have really happened, sometimes shockingly recently (the Fore people of Papua New Guinea were practicing cannibalism as late as the 1960s). The truth is, you don’t need to be a monster to eat another person. Even we would do it, if circumstances required. If we are only three missed meals away from anarchy, how far away is cannibalism? Four missed meals? Five? The day might come, and then we will see how much ironic distance Cannibal Holocaust has.

It’s shot well. It has a strong atmosphere. It has all the grace and subtlety of a flint axehead crunching through your parietal lobe. There are some good performances. It is a good movie, by many categories.

But it’s filth. Not just at the surface, but right the way through. After a wave of bannings, censored cuts of it were released, but they did no good. You can’t wash clean a pair of hands that are made of dirt.

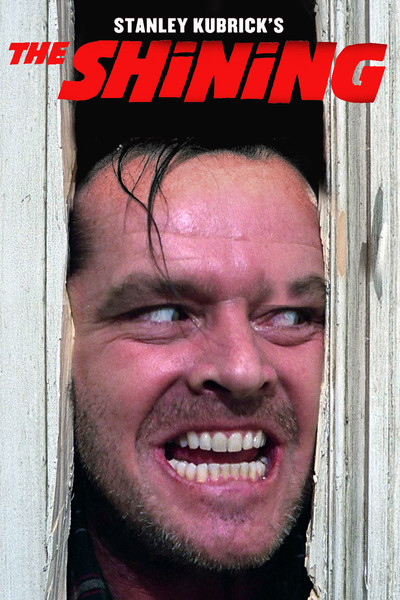

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.

This obsessive approach actually made his films less perfect, as it increased the odds of a continuity error between shots. Kubrick’s films are a target the size of a barn door for the forces of entropy, and indeed, the final cut of the Shining has a lot of goofs. Furniture mysteriously moves between shots. Danny’s sandwich has different bite marks.

I think Kubrick must have been aware of this, because The Shining also contains extremely big and easily fixed mistakes, ones that a perfectionist surely would have noticed. At the start of the film, the caretaker who murders his family is named Charles Grady. But when Jack Torrance meets the caretaker (or his ghost), he introduces himself as Delbert Grady. The climax of the movie involves a chase through a hedge maze, but, but in the opening aerial shots (where we see the entire Overlook Hotel) there is no hedge maze on the estate.

These blunders are so big and showy that they seem intentional. They’re so clearly part of the movie that one attaches thematic significance to them (Jack’s perception is unreliable, the hotel is not as it seems, etc), and maybe Kubrick was hoping we’d also attach thematic significance to the smaller ones, too. After all, a mistake is only a mistake when you admit it. Everyone knows that when you mess up performing a martial art kata, you don’t hastily correct. You make it look like you meant to do that.

If this was Kubrick’s strategy, it worked. Mssage boards are full of thematic analysis of the different bite marks in the sandwich, and so forth. Nobody will believe that he was actually capable of making a mistake.

Stephen King famously didn’t like this adaptation. Kubrick probably couldn’t have adapted any of his works to his satisfaction, except maybe for Christine, which is about a car. Kubrick’s movies are very cold, and although sometimes full of human energy, they usually don’t have a human heart. Jack hacking through a bathroom door is scary the way a wind-up machine doing the same thing is scary. King’s novel invites us deep into Jack’s psyche, while Kubrick’s movie turns him into another scary thing in a house full of scary things.

Were these intentional stylistic touches? Or where they deficiencies in Kubrick’s storytelling abilities? Because of Kubrick’s tactics, I’m not sure. At a high level, it’s difficult to tell a feature from a bug.

I feel the same way about the changes to the story’s lead. In the book, Jack Torrance is a nice guy with a monkey on his back. In the film, he’s a terrifying alien almost from the beginning. His suit doesn’t fit. He pounds the keys on a typewriter as if it’s a boxing match. When his new employer asks if his wife is comfortable staying at a hotel with such a gruesome history, he replies with something like “she’s a confirmed ghost story and horror film addict!”, hitting a jarring combination of weird and socially awkward. Every time he smiles, it’s an uncertain smile, as if the reptile inside is worried about tearing the human skinsuit.

Almost all of the film still holds up. It cuts out most of King’s self-indulgent touches (the living hedge maze animals, the jar of wasps), leaving a story that’s very slow while never dragging. You feel the passage of time, and the alienation from the outside world.

I think he damaged Shelly Duvall’s sanity, though. The woman just isn’t right.