Getting banned from Wikipedia because I keep adding “snuff film” to Thomas Edison’s list of inventions.

Getting banned from Wikipedia because I keep adding “snuff film” to Thomas Edison’s list of inventions.

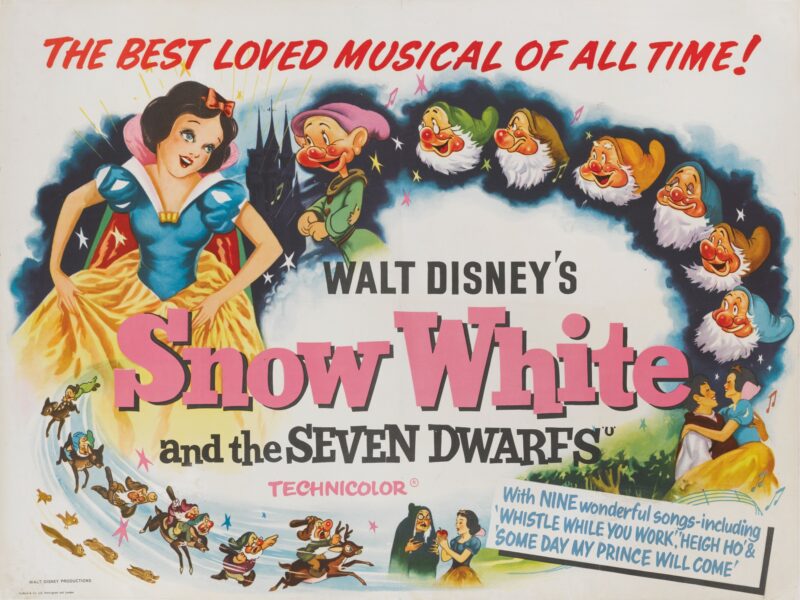

They called it Disney’s Folly. They thought the film—produced in the depths of the Depression on an unprecedented 1.5 million dollar budget—would ruin the company.

But folly is an interesting word. Trace it back in time, and it turns black and strange. Folie, in Old French, means madness[1]Disney comes to us from French, too. Disney = D’Isigny = “From Insigny.”. Venture even further back, and it gains connotations of wickedness, sin, and lewdness. Disney’s Crime.

He got away with it. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is the most important animated movie ever made. It’s like Marquis de Sade’s Justine or Edgar Allen Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue—hard to appraise as good or bad because of its singularity. Nothing like Snow White exists before it. Everything made afterward lies in its shadow. It was the first feature-length cel-animated film, and purely on a technical level, it’s a masterclass. The opening truck-in shot of the castle uses the studio’s new multiplane camera to evoke a sense of sky-devouring depth. Snow White is rotoscoped from live-action footage, which lets her interact believably with a rope, a bucket of water, and a door. Skirts and curtains swish convincingly. The sense of physics is bang-on accurate. It’s loaded with little “how did they do that?” moments, like when Snow White stares into a well and ripples play across her reflection.

The start of the film is jokeless. You are not supposed to laugh. That’s another area where Snow White broke the mold: it told a slow-paced romantic drama at a time when animation meant Koko the Clown and Felix the Cat. It was an audacious reimagination of form: almost like a three hundred million dollar, 90-minute long Tiktok. Disney spent big money on an artistic risk.

But there was a strategy to the movie, too. Walt viewed cartoon shorts as a financial dead end, and was probably right. Shorts were lashed to the mast of feature-length movies and had to share their profits: Disney could conceivably spend tens of thousands of dollars animating a short only to get stuck on the same bill as a box office turkey and never earn back the money. The only way to make this work was to turn out shorts as cheaply as possible, which Walt resented. By the mid 30s, the film market was glutted with animated content, and though Walt lived decades before Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne came up with Blue Ocean Strategy, he grasped its main insight: don’t compete; differentiate. By continuing to make shorts, he would be racing Warner Bros, MGM, Van Beuren Studios, Terrytoons, and Fleischer Studios to the bottom. But nobody else was making animated feature films, so he’d only be competing with himself.

Yet it’s still an odd film. It still feels like it shouldn’t work. Urban legends flower from this film’s remains: I still occasionally hear the one about how the dwarves are named after the stages of cocaine abuse. That sounds stupid, but the movie shunts your mind down strange pathways. Like Wizard of Oz, its stagey cuteness feels like a disguise that might drop at any minute.

You might remember the scary scenes, and how horrible they seemed when you were a little kid. The explosive and kinetic chase through the forest (even though nobody’s chasing her!) brings claustrophobic panic to your chest. The queen’s transformation scene is directed like a Hammer horror film. The interior shots of her dungeons have the luxuriant filth-texture of nightmares. It has moments of surrealist whimsy, yet there’s a heartbeat of German Expressionism pulsing through it.

That’s one half of the film. The other half consists of singing dwarves and twittering birds and gag-based slapabout comedy driven by the Roy Atwell, Pinto Colvig, and Eddie Collins characters. As soon as Snow White arrives at the cottage, the movie enters a thirty-minute stretch of downtime where the dwarves fool around and nothing much happens. Even the animation style changes: when the dwarves wash their hands for supper, they do so in generic blue cartoony water. This sequence feels like a couple of animated funny shorts strung together.

Snow White is a complicated movie to analyze. It innovates, but also contains reprises of everything that had made Disney successful up to that point. From one angle, the movie is a radical experiment; from another, it hedges its bets.

I’ve come to like the dwarves and animals, even though they’re pointless to the plot. They’re like flowers growing up a tree—they don’t structurally support the tree at all, but the world is better when flowers grow. The dwarf stuff is the soul of the film. You could cut it all out and never know it was gone, but you wouldn’t want to: it’s an oasis of chaotic energy in a film that’s otherwise pretty staid.

Snow White takes a famous story and plants it with ramrod straightness into your forebrain. Essentially, Snow White escapes from her stepmother, who is trying to kill her. She finds refuge with some very small men, is laid low by her stepmother’s poison, and then a prince restores her to life with love’s first kiss. All the human characters (save the stepmother) are stiff and starched down, both in their designs and expressiveness. Walt Disney discovered the same thing everyone from Max Fleischer to Ralph Bakshi would later discover: rotoscoping adds realism, but kills spontaneity and emotion. Snow White dies…but, for me, this moment lacks sting, because she never seemed fully alive to begin with.

(Realism is absolutely a mixed blessing in animation, which draws its appeal from the fact that it’s not realistic. John Kricfalusi used to bitch about this on his blog. “Who cares if the water in an animated movie is photorealistic? I can see photorealistic water any time I want by running by kitchen sink.” I don’t entirely agree with this—technique is good, and craft is good—but I partly agree. At a certain point in the quest for realism, shouldn’t you just be shooting in live action?)

The dwarves are lively enough to compensate for the stiff-seeming humans (and are characterized far better than they have to be), but even they are archetypes, not characters, and the story is made of tropes, not events. You can ask lots of hard questions about the movie, such as how the prince knew where to find her, or how the dwarfs fashioned a complex glass display case, but ultimately, the answer is always “because he wouldn’t be the prince otherwise, and they wouldn’t be the dwarves”. Everyone has some essential Platonic nature that they have no choice but to fulfil.

This is exemplified in the stepmother (who everyone agrees is the best part of the movie, a dry run for Maleficent). At the start, she’s a queen. But this makes her risky, failure-prone plan to poison Snow White nonsensical. Can she just snap her fingers and have Snow White arrested on whatever grounds she likes? Why get personally involved? Well, once she drank the magic potion, her nature changed. She’s no longer the queen, with a kingdom. She’s now a witch, forced to rely on “eye of newt and toe of frog, wool of bat and tongue of dog.” You can’t be both a queen and a witch, in a story like this. You can only be one at a time. That’s fairy tale logic. Snow White owes many debts to the past: the question is whether the past wants those debts on its ledger books. Was Disney suitably respectful to the tale? Did he get away with his crime?

To answer that, it’s worth discussing where Snow White came from.

The answer, approximately, is “Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm”, who published the story in 1812 as Sneewittchen. It’s often asserted that the Grimm brothers “transcribed” fairytales. That’s not quite right. They bred them, like Mendel and his peas. First they collected samples (at least seventy-five different versions of Sneewittchen exist), selected their favorites, combined different elements from different stories, and sometimes wrote new scenes out of whole cloth. They shamelessly altered the contents of their stories to suit reader tastes. They changed rapes into kisses; lustmord into passionless, offscreen death. In other words, they did similar things to Disney. Don’t regard the Grimm brothers as cool OG gangstas and Walt Disney as Vanilla Ice rapping lamely about harpoons and bacon. They lived a century apart, but were more alike than different.

Snow White (in many pre-1812 accounts) is taken off to be killed by her mother. This evidently disagreed with Wilhelm and Jacob’s stout Volkish piety (“Honor your father and your mother“—Exodus 20:12), and they altered the tale so the queen was Snow White’s stepmother. This was sanitization. Nobody likes the idea that a monster could be your mother. It’s better for the evil to come from “outside the house”. (I believe a similar process happened in Hansel and Gretel, whose mother at least has a more sympathetic motivation than Snow White’s).

The Grimm brothers excised any trace of local history. For example, the idea (promoted by historian Eckhard Sander in Schneewittchen: Märchen oder Wahrheit, published in 1994 by Wartberg Verlag) that Snow White is a fictional cipher for 16th century Countess Margaretha von Waldeck (who died in 1554, of poison, perhaps), and that the “dwarves” were actually army of child slaves who toiled underground in her father’s mines near Bergfreiheit.

Jacob and Wilhelm were aware that they were changing the stories. In the accompanying notes to Sneewittchen, they list all the variants they had found. In one of them, the queen has a male consort, who takes a distressing pederastic interest in Snow White (this version was memorably retold by Angela Carter in The Bloody Chamber). In another, the queen’s “mirror” is a talking dog named Mirror![2]Grimm’s Household Tales, notes to tale 53 They would have defended themselves by saying that there never was a “definitive” Snow White: these were oral tales, huge thrashing stormclouds with no defined shape. A fairy tale, by definition, is told: they lash out in a slightly different direction every time the teller speaks it to life. What parts get thundered out in the tones of a Biblical prophet? What parts get mumbled quietly through? What parts get skipped entirely, because the teller thinks their audience is too young, too stupid, or too morally hidebound to hear them? These decisions don’t damage the tale, they are the tale. The way a story is told is indivisibly part of it.

Writing is a unique kind of telling, because locks the story down permanently, giving it a fixed shape. What’s the movie’s very first shot? A book opening. It’s a motif suggesting that this version, and no other, is the definitive reading. “Ah, now we’re getting the story as it really happened.”

…but the appearance of permanence is illusory. Paper is cheap. Writing a book doesn’t define a story forever, because someone else can just write another one. The next version of the story doesn’t replace the first, it exists independently from it. We end up with a multiplicity of babbling mouths fighting to be heard, each possessing either all the truth, or none of it.

Once, someone wrote a book where Santa Claus is gay and has a husband. The anger this provoked—“You ruined Santa!”—seemed odd to me. Is the imaginary character of Santa now gay forever, because one book depicts him so? Can only one portrayal of Santa exist at a time? No. The world has enough room for an infinity of stories. Disney did not “ruin” Snow White: he just made his own variant.

And even if he hadn’t done so, Snow White still would have changed with time. Every reader is different, and brings a different interpretation to the story. Older generations would have been horrified by a parent trying to murder you. Modern generations are horrified when a prince kisses a princess without her consent. We all bring our own baggage to the tale. In a sense, no child has ever directly read an actual fairy tale, except through a silt-like layer of their own modernist and postmodernist sensibilities (just like nobody has ever seen an actual dinosaur bone, only modern mud packed into the shape of one). I’d argue that the longest-lasting part of a fairytale isn’t the plot, its the cruelty. The classic format is “once upon a time…”, then events dark and horrible occur, and we finish on an insincere-sounding “…and they all lived happily ever after”. A fairytale offers comfort, then sticks a knife into the reader or listener when they’re most vulnerable. It’s a devastating trick that every child of every age is vulnerable to.

Beyond this, many fairytale are textually ambiguous. They’re also, to be blunt, uncomfortable. Many seem like naked accounts of manias and mental disorders and abuse: ideas that pre-modern people had little way of meeting, except on the grounds of myth and folklore. The stock Grimmsian figure of the “Unglückskind” (“child of bad luck”) could be read allegorically as childhood autism or ADHD. It’s easy to be split, banished into a kind of fairytale world. A single head injury can transform your perception of the world, so that you might as well be locked in Gothel’s tower. Sometimes a child is mad. Sometimes mom and dad are mad. Sometimes they both are. Fairy tales echo some of such ineffability of trauma: but they are also hopeful, because they redefine it in a way we can understand. It’s easy to justify changing an abusive mother into a stepmother, in that light. When you make that change, are you ruining the story, or improving it? There’s more than enough cruelty in the world. Do we also need our stories to be equally cruel?

Disney power-sanded off a lot of fairy tale ugliness, but it doesn’t really matter. Interesting fairy tales are so stark that even after you blunt their edges, you still feel where the edges should have gone. And you definitely do in Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

And there’s still some delightfully fucked-up stuff that got added. Disney loved a good skull gag. I counted three separate times when a bug or a rat or something crawled out of a skull’s eye sockets. My favorite gag in the movie involves the skeleton in the dungeon, reaching for a water jug that’s just a little out of reach. You learn so much about the witch’s character from that scene. “Have a drink! Hahaha!”

But in an odd way, the light scenes act as elastic rubber bands to propel the dark scenes forward, so that they hit harder than they otherwise would have. What I’ve often felt is that Disney’s mannerly Protestantism makes their ugly moments even worse. Everyone accepts cruelty and evil from Loony Toons: when Elmer Fudd tries to shoot Bugs, well, that’s just how Clampett, Jones, Avery did things. But when Donald Duck puts a gun to his head and tries to blow his brains out, it feels real and shocking, because you don’t expect that from Disney. Only a conservative square can be genuinely outrageous.

I wonder what kids today think of movies like this. Have they been reprogrammed by CinemaSins to snicker and count plot holes, instead of meeting the film on its own ground? What emotions does it produce?

I watched Snow White when I was a stupid kid, and it left a deep impression on me for that reason. Thanks to the internet, stupid kids are a dying breed. Well, they’re still stupid—but it’s a different kind of stupid: precocious adult stupidity, children trying on ill-fitting masks of performant irony they learned from the internet. I structure my life so I hear as little of the thoughts of children as possible, and what I do hear dismays me. “Oh, right. You’re a twelve year old.”

I saw a video where a primary school teacher discussing what motivates the kids she sees in her classroom: cringe avoidance. Kids are now terrified of doing things considered “cringe”, or being called cringe, or fundamentally being cringe (as though it’s a rash you can get infected by), and arrange their entire personality and behavior around that goal.

This impacts how they view media, because being moved by art—opening your heart, and letting it scar you—is deeply cringe. This leaves movies in a weird place: they exist to be rejected. Kids watch scary movies so they can show they’re not scared. They watch sad movies and refuse to cry. They watch funny movies and intentionally don’t laugh. Always, they have to be better than the thing they’re watching.

I don’t think this movie would work for modern kids. They’d see it as an invitation to pour scorn and contempt on its millions of hand-painted cels and beautiful artwork and laborious performances. They are ocean promontories, and the movie is a wave crashing around them, leaving them unmoved and unchanged. Their identity is based around the slaughter of art and all it means. Mirror mirror on the wall, who is the least cringe one of all?

References

| ↑1 | Disney comes to us from French, too. Disney = D’Isigny = “From Insigny.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Grimm’s Household Tales, notes to tale 53 |

A certified “nu metal” horror movie, The House on Haunted Hill caused my hair to erupt in bleached tips, my pants to baggify themselves, and a 40 foot long wallet chain to explode out of my pocket, uncoiling like the weapon of a Mortal Kombat character. Suddenly, wounds were crawling through my skin. I try so hard and come so far, but in the end it doesn’t even matter.

It’s pretty good, overall: a gimmicky but scare-packed film with creative VFX, and even inspiring hints that there may be a real, live human writing the script. I don’t remember much of the 1959 version (except it has Vincent Price), but I remembered lots of things from this one. The pencil through the neck. The theme park ride. The shit with the camera. The other, different shit with the zoetrope (the movie doesn’t trust you to know what that is, they call it an “Saturation Chamber” or something). The waterboarding part. The sheer volume of practical effects was enjoyable. The editing is great, and creates massive amounts of chaos from William Malone’s workmanlike direction. It uses that strobe-pulse fluttery-moth shot-through-a-spinning-fan trick you saw in Jacob’s Ladder, to the point where it becomes a fetish. Don’t watch this if you have epilepsy.

The design of The Darkness (the embodiment of the evil in the house, not the rock band) walks a fraught line between “mediocre late 90s CGI that hasn’t aged well” and “genuinely creative and unsettling”. That one shot where they map an animated texture over a 3D model looks terrible, like a videogame.

…but the more abstract Rorschach-blot design looks excellent.

Casting is, admittedly, not the movie’s strong suite. Geoffrey Rush plays a ludicrously hammy 1950s panto villain. Fun, but what’s the point of updating the movie into the 90s and then writing such an anachronistic character? Xenia Onatopp (or whoever plays his wife) is okay. The camera operator appears to think I really want to see down her dress. Unfortunately he is correct.

The rest of the actors are bland. You will not remember their names. If you deign insert them into your memory, it will be as Reporter Bitch, Camera Bitch, Eyebrows Man, Glasses Man, and Black Man in a Horror Movie (he actually lives to the end. They should award him the Purple Heart for that. He gets characterized as a professional basketball player…one of those NBA pros who’s 1.78m tall, I guess.) Holy boring. Where do they find these people? Were they shipped to the film studio in a packing crate from Boring Actors Inc? They should have ripped the crate apart, painted terrified faces on the wooden planks themselves, and used those in the movie instead. It would have afforded us the illusion of more lively and charismatic actors.

Overall, there’s a lot of great moments here to offset the 90s cheese. I was surprised by how well the film held up.

I did notice some thematic elements that sailed over my head when I was 12, like the Scientology angle. It’s one of the most cartoonishly anti-psychiatry horror movies I’ve ever seen (“Electroshock therapy. Dr Vanacutt liked to zap his patients in multiples of eighteen. More energy efficient.”). Or the moment when Evelyn says (referring to her husband) “His initials are S.P.”

That might also explain this lengthy monologue by Ali Larter’s character, when she attempts to defeat the Darkness using the science of Dianetics.

I think it’s a privilege to call yourself a Scientologist and it is something that you have to earn. Being a Scientologist, you look at somebody and you know absolutely that you can help them. Being a Scientologist, when you drive past an accident, it’s not like anyone else. As you drive past, you know you have to do something about it, because you know you’re the only one that can really help. That’s…that’s what drives me, is that I know we have an opportunity, and uh, to really help for the first time effectively change people’s lives, and uh, I’m dedicated to that. I’m gonna, I’m absolutely, uncompromisingly dedicated to that. We are the authorities in getting people off drugs. We are the authorities on the mind.

I found that a little heavy-handed, but your mileage may vary.

Also, I am pretty sure I reviewed this movie already. Oops.