Once, I heard a description of Family Guy that cuts right to the heart of the show’s failings. “The Simpsons, if every character was Homer.” Everyone’s crazy, everyone’s a clown, everyone’s the Lord of Misrule. Everyone’s a Punch and nobody’s a Judy. It’s a common failing in comedy: “the straight guy is boring. The screwball gets the laughs. So if we eliminate the straight guy and have two screwballs, it will be twice as funny!”

Once, I heard a description of Family Guy that cuts right to the heart of the show’s failings. “The Simpsons, if every character was Homer.” Everyone’s crazy, everyone’s a clown, everyone’s the Lord of Misrule. Everyone’s a Punch and nobody’s a Judy. It’s a common failing in comedy: “the straight guy is boring. The screwball gets the laughs. So if we eliminate the straight guy and have two screwballs, it will be twice as funny!”

The straight guy provides ballast, you fool. Comedy’s like a game of table tennis. You can get pretty creative playing it, slamming balls off the wall while standing on your head. But it only works if you have a stable, unmoving net.

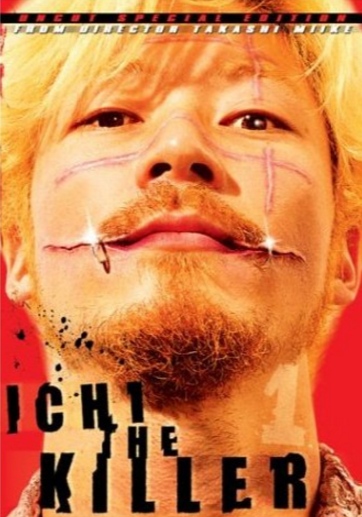

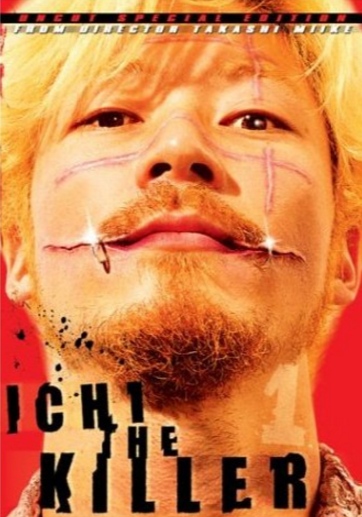

Ichi the Killer is not quite a comedy but has a similar weakness. It draws us (or perhaps anti-draws, given that it’s an adaptation of a Hideo Yamamoto manga) into the world of sadistic yakuza enforcers, and asks us to bask in the sangfroid of one particular sadistic yakuza enforcer, who is different to the others to the extent that he has scars on his face.

I don’t know what’s supposed to be shocking and awful and Ichi. Everyone in this film is a repulsive person. Gangsters crack jokes while scraping bloody remains off ceilings. Sociopathic prostitutes manipulate their johns. The movie sets gray against a backdrop of slightly lighter gray. It’s a good setting, but it needs some contrast. It needs a “straight guy”. It’s Family Guy all over again. If Homer’s the baseline, then Homer stops seeming shocking and funny – he’s just just the way things are.

I like the scars on Ichi’s face. A “Glasgow smile”, as they call it a few thousand miles away. The film’s best scene comes early on, where we see Ichi blow smoke through the cuts.

Elsewhere, the film’s aesthetic is less successful. The violence is undercut by the fact that 1) the effects are cheap and 2) the acting doesn’t sell us on the brutality. There’s a scene where Ichi tortures a man by puncturing his cheeks with an alarmingly huge pin…and in between bouts the man speaks calmly and lucidly. It’s like watching a WWE pay-per-view where wrestlers bounce back up after getting chairs smashed over their head.

Later, the effects team just gives up trying. CGI looked better in 1993. The remaining wheels fall off the movie’s wagon when we get to horrible special effects that look like a SyFy movie made in an antifreeze lab.

I haven’t read the manga, although I read Yamamoto’s other big work: Homunculus. It was fascinating, for what it was, but he doesn’t seem to be very adaptable as a mangaka. That might have been Ichi the Killer’s undoing. Generally, there are two schools of adapting manga: the first is to capture everything, the second is to try to capture the “spirit”. Both of them can fail horribly, but in unique ways. Judging unseen, this feels like the first case. You can’t shove ten volumes of manga into a DVD player, and you shouldn’t even tr

This was crying out to be something like that Cronenberg film, Eastern Promises, particularly that scene in the bathhouse, involving linoleum cutters. That moment was what this movie dreams of being when it grows up. Now, it’s just blowing smoke.

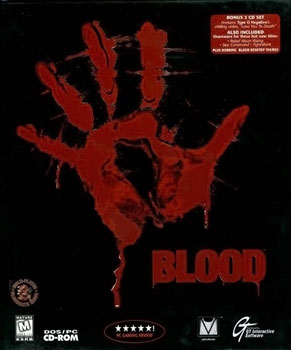

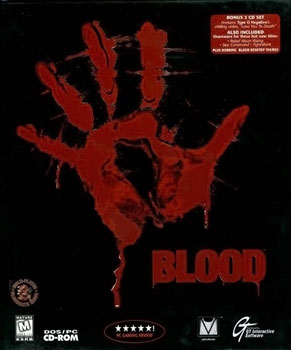

Films such as The Cabin in the Woods are often described as “a love letter to horror.” Monolith’s 1997 first person shooter Blood is more like a rambling, 50 page Unabomber manifesto stuffed into horror’s mailbox at 2:00am, complete with the final line “ps: nice view thru yr bedroom window ;)”. Conceptually it’s one of most ridiculous and nebbish games ever made: the dialogue consists of groan-worthy riffs on famous horror movies, the levels are themed off places like the Overlook Hotel and Crystal Lake, the game shoves references to Lovecraft and George Romero under your face with such obsessive frequency that you almost want to pat it on the shoulder and say “Relax, I get it. Stop trying so hard.”.

Films such as The Cabin in the Woods are often described as “a love letter to horror.” Monolith’s 1997 first person shooter Blood is more like a rambling, 50 page Unabomber manifesto stuffed into horror’s mailbox at 2:00am, complete with the final line “ps: nice view thru yr bedroom window ;)”. Conceptually it’s one of most ridiculous and nebbish games ever made: the dialogue consists of groan-worthy riffs on famous horror movies, the levels are themed off places like the Overlook Hotel and Crystal Lake, the game shoves references to Lovecraft and George Romero under your face with such obsessive frequency that you almost want to pat it on the shoulder and say “Relax, I get it. Stop trying so hard.”.

But it’s also one of the most fun shooters ever made. There’s just no cohesive direction to any of it, and strangely, that completely works.

You have 1) a brainless “shoot everything that moves” gameplay, 2) paired with a complicated set of RPG -style damage modifiers (as a simple example, stone gargoyles repel fire attacks). You have 1) a nonsensical throwaway plot about an old west gunfighter (with anachronisms galore), and 2) a very detailed mythos, right down to the fact that the enemy cultists speak a constructed language (there was a dictionary on the now-defunct Blood site, revealing said language to be the product of hurling Sanskrit and Latin at each other in a Participle Accelerator.) You have 1) shitty graphics (the Build engine was dated in 1996, and even more so in 1997), and 2) fairly groundbreaking use of 3D voxel imaging (for tombstones and such). Blood’s an anomaly.

The game’s a mess, in the best way possible. It’s like it was made by two different teams living on two different continents who could only communicate by carrier pidgeon. “Throw a bunch of interesting ideas together” seldom works, but here’s the exception.

I’ve played through it several times, at various difficulty levels, and I still find it capricious, challenging, and occasionally brilliant. The Build Engine isn’t the prettiest whore on the waterfront, but it allows for destructible/deformable environments and the game takes those features and runs like they’re a pair of scissors. E1M3, “The Phantom Express”, takes place on board a moving train – it’s stunning as a visual effect, and the level design perfectly complements it: you have to fight tense gunbattles in narrow train corridors, etc. The only bad thing is that none of the later levels quite match it in creativity.

The weapons are savage and visceral (though I never figured out exactly how the voodoo doll work), and the level design fun, flowing, and filled with endearing human touches. Duke Nukem 3D was the anti-Quake. This is the antier-Quake. This is the final and complete triumph of content over technology, and nobody in gaming realised it, either then or now.

Not even Monolith did – Blood II was an inexplicable attempt at remaking this game with zero character or charm. And of course, the game still has a modding community.

Blood isn’t perfect. The final boss is the easiest one in the game. The weapons aren’t balanced all that well (generally, the cooler a weapon seems, the less useful it is in the game) and some of the enemies are truly ridiculous bullet sponges. It’s bimodal nature means it has daring creativity paired with cloddish FPS cliches – there’s the old “shoot a crack in the wall to reveal a secret area” wheeze…again…and again…

But it’s classic, and the rarest type of game: one that is impervious to time. To preserve a human body, you generally extract all eight litres of blood – and I guess this is where it all ends up. Duke Nukem 3D came out a year before and laid the ground for this type of game (gory violence + campy irreverent humor), but between the two of them, THIS is the one to play first, and perhaps last.

Imagine you have a friend who tells you a joke about their prolapsed rectum. You laugh. It was sort of funny, and also they’re your friend. Their eyes light up, and the next day they come back with an entire notebook full of prolapsed rectum jokes, and the expectation that you will listen to and enjoy all of them. At what point do you stop laughing? At one point do you say “look, I’m at saturation point. Enough about your stupid rectum. I liked the first one but I don’t want to hear them for infinity.”

Imagine you have a friend who tells you a joke about their prolapsed rectum. You laugh. It was sort of funny, and also they’re your friend. Their eyes light up, and the next day they come back with an entire notebook full of prolapsed rectum jokes, and the expectation that you will listen to and enjoy all of them. At what point do you stop laughing? At one point do you say “look, I’m at saturation point. Enough about your stupid rectum. I liked the first one but I don’t want to hear them for infinity.”

This is how I feel about Sabaton.

It’s a mistake to think this band makes music. That would be like saying Adam Sandler makes movies. This project is just Joakim Broden, pulling a lever over and over and over, until his fucking hand falls off. It’s cynical. It’s formulaic. It’s artless. And it’s all our fault. We rewarded laughed along with the joke once, and now we get to listen to Sabaton forever.

You know what’s coming. The Last Stand is another plastic collection of charmless Nuclear Blast Metal, filled with horrible forced-catchy singalong choruses, and the band buried underneath a mountain of choirs and keyboards. If you’re wearing a Pewdiepie shirt and need a score for your next gaming marathon, go and make your day. If you have a brain in your head, you’ll hate this with every fiber of your being.

This album has some of the worst choruses I’ve ever heard – we’re talking Dream Evil shitty. Lead-off song “Sparta” has Broden singing (which is obviously a Platonic bad idea) and a stupid “HOO-HA” gang shout that gives me douche chills. Several songs like “Rorke’s Drift” and “Hill 3234” don’t even have chorus melodies, just Broden belting some lines in that staccato manner of his (nice to see Sabaton writing double-bass songs, though). “The Last Battle” is just irritating AOR gloop. Battle Beast does this better. Battle Beast does everything Sabaton does better.

The production is slick and clean. The songs are hobbled around the three minute mark. The album is short, and padded with bonus tracks nobody gives half a fuck about. The military theme is hampered by the fact that they’re running out of good battles to write about: on their next album they’ll be down to writing about the time Gene LeBell choked out Steven Seagal and made him shit his pants.

This review is dogshit, but there’s just so little to talk about. It feels like trying to analyse elevator music. Listening to The Last Stand just makes me feel sad and empty. The music’s a nonevent, but did they have to steal Tommy Johansson? Forget getting a new Reinxeed album any time soon.

The Last Stand will keep Sabaton on the festival circuit a little while longer, and all the critics listen to a few songs then copy+paste their “7/10, gives the fans what they want” review from the last album, and meanwhile, the genre keeps spinning its wheels. Power metal isn’t a magical unicorn. It’s a rotting donkey carcass with a novelty dildo glued to its head, and every day, the stench becomes harder and harder to disguise. There’s going to be a shakeup soon. This is exactly the sort of stagnation that led to the overthrow of metal by grunge rock in the 90s. Until then, enjoy the rectum jokes.

Once, I heard a description of Family Guy that cuts right to the heart of the show’s failings. “The Simpsons, if every character was Homer.” Everyone’s crazy, everyone’s a clown, everyone’s the Lord of Misrule. Everyone’s a Punch and nobody’s a Judy. It’s a common failing in comedy: “the straight guy is boring. The screwball gets the laughs. So if we eliminate the straight guy and have two screwballs, it will be twice as funny!”

Once, I heard a description of Family Guy that cuts right to the heart of the show’s failings. “The Simpsons, if every character was Homer.” Everyone’s crazy, everyone’s a clown, everyone’s the Lord of Misrule. Everyone’s a Punch and nobody’s a Judy. It’s a common failing in comedy: “the straight guy is boring. The screwball gets the laughs. So if we eliminate the straight guy and have two screwballs, it will be twice as funny!”