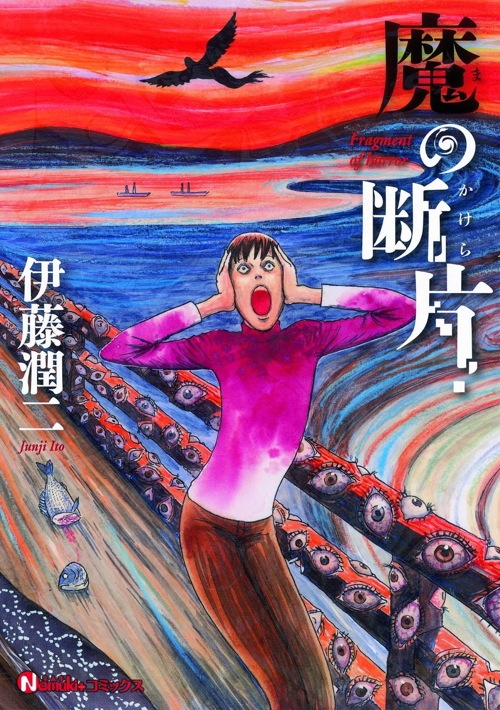

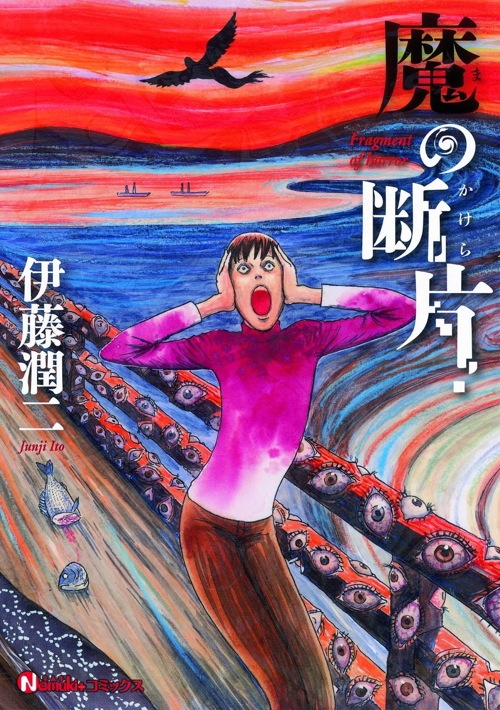

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.

Why doesn’t he age? Clearly, black magic is afoot. I don’t know the specifics of his deal with the devil, but I’m they involved eternal youth, in exchange for nobody ever being able to translate him to English.

The evidence is overwhelming: the landscape is littered with failed attempts to get this man in English. In 2001, ComicsOne licensed his 16-volume Horror Collection series, released the first three in English, and then vanished from the face of the earth. In 2006, Dark Horse licensed his 12 volume Museum of Terror collection, again released three, and then cancelled the series for reasons unknown. In 2011, an online manga website called Jmanga opened with Ito’s Voices in the Dark as one of its launch titles…and folded, less than two years later. Most recently, Ito was conscripted to work on Silent Hills, and then the project was given a brutal gangland-style execution by Konami. The Junji Ito Curse is not to be mocked.

Viz has licensed several Ito properties in the past, and (perhaps foolishly) has now given us one more: Fragments of Terror. Frankly, I think they are now living on borrowed time. You don’t bring Junji Ito to English and escape the consequences. I expect to wake up tomorrow and find that they’re filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, their headquarters have been overrun with flesh-eating spiders, and their CEO’s athletes’ foot is flaring up.

Fragments of Terror collects one-shots from the last few years of Ito’s pen. They’re a mixture of inventive JG Ballardian concepts, scary campfire dread, horror movie camp, and Ito’s excellent art. Not everything in here is great, and it doesn’t disguise the “serial manga fingerprints” as well as it might, but it’s still a worthy addition to the slim lineup of English Ito titles.

Affairs start with “Futon”, a story about a mattress that induces hallucinations when you sleep on it. Not one of Ito’s best efforts. Very dull and one obvious, with a pat, tie-a-bow-on-it ending. “Wooden Spirit” is stronger, with Ito drawing an inspired link between the curves of a woman’s body and the natural geometries of plants, trees, et cetera. No real attempt at a story, but the execution and art is impressive.

Issues of tone from one story to the next soon jump out at the reader. The understated “Wooden Spirit” gives way to the comical and gruesome “Tomio – Red Turtleneck”, followed by borderline shoujo bait in the sappy and sentimental “Gentle Goodbye”, followed by the ultra-violent “Dissection-Chan”. The stories whiplash erratically from one mood to the next. Why put the stories in chronological order? Why not take advantage of the opportunity to craft a bit of an arc, to build and release tension?

The best and worst story in the collection sit right next to each other. “Magami Nanakuse” involves a girl journeying to meet a mangaka she admires, and then…well, remember “Ghosts of Golden Time”? It’s that crap all over again. Very awkward and ham-fisted attempts at social commentary here, as well as a lack of focus or direction.

But “Blackbird” is a great. Intelligent, well paced, scary as hell. A man is rescued after apparently spending a full month trapped in the wilderness with two broken legs. How has he survived his ordeal? Things keep building and building, and the ending satisfies without explaining too much. I’d put this story up against anything from Ito’s classic period (1997 to 2002 or so).

In the end, if nothing else Fragments of Terror offers a statement to the fact that, despite all the events of the last ten years (marriage, fatherhood, pacts with the devil, etc), he’s still capable of serving up the goods. He’s still in love with waifish female leads, elaborate dresses soaked in blood, grotesque imagery, and stories that make no sense but have you nodding in perfect agreement.

Ito might be in cruise control mode, but he’s still here, and Fragments of Terror is an interesting if uneven collection from an underrated mangaka who’s still making inroads to the English market. No doubt Viz’s corporate headquarters will be smoking and charred rubble by tomorrow, but they did a good job here.

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.

This is a 1991 anthology from Creation Books, back when they were Creation Press. Their basic approach is to pack various surrealist authors whose names start with B (Burroughs, Bataille, Banks, Britton) into a dense ball and insert said ball through your horizontal fissure at 300 miles per hour while giving the middle finger to boring lamestream media conventions like “design” and “print quality”. The pages in my copy are literally falling out. It’s poetic, as if the collection’s depravity is causing it to explode in my hands. Bad luck that I lost the page of contents, because now it’s hard to find my favorite stories.

The best one is the reprint of Ramsey Campbell’s, “Again”, which features flies, a corpse, and a gestalt: a terrifying and suffocating sense that you’re lost in a repetitious and unending cycle. Autoerotic strangulation via Moebius loop. Creation does come across as a “getting all my buddies in print” vanity enterprise at times (it helps if you understand that many people in this book don’t exist, and are pen names for other authors), but writers like Campbell and Burroughs hint at an ambition to be more than that.

Terence Sellers furnishes an excerpt (from The Correct Sadist) that is short and twisted. Not fifty shades of gray, one shade of black. David Conway’s story “Eloise” (which you can find collected in Metal Sushi) melds the old and romantic with futuristic anodyne and chrome. I’d already seen this story in one of his collections but was glad to read it again. Is this its original printing?

Then there’s “James Havoc”, contributing “In and Out of Flesh”, a fragment which appears in a more polished form in his Butchershop in the Sky compilation (and again as a full-blown graphic novel form in 2009). A teenage biker gang commits sadistic sex murders, literally writing return to sender on the bones of their victims. This early version is oddly unHavoclike – adjectives are relatively few, there’s no wild Burroughs-esque “literary guitar solos” a’la Satanskin, and generally it’s more like a story than is usual for this writer. The end of the collection promises a forthcoming (and still unreleased) children’s book from Havoc called Gingerworld, which (again) appears in fragments in Butchershop in the Sky.

Then there’s the usual filler. James Havoc’s girlfriend. A blink-and-you’ll-miss-it excerpt from Jeremy Reed. Prose from Clint Huczulak. Poetry from Aaron Williamson. They fulfill one purpose: increasing the page length beyond chapbook size into an actual anthology. None of these works were memorable in any way.

The final story, Paul Marks “And the Sun Shone by Night”, woke me from my torpor with its sheer brutality. Its first few pages make it sound like a a heavy handed tract about animal testing, but the following content is so extreme that goes straight past being a moral fable and becomes a Gommorral fable, if you like. Who’s Paul Marks? His generic, unGooglable name makes me think he’s still another pseudonym.

Red Stains is a nice look at the prime years for one of Britain’s early “extreme fiction” publishing houses. While their later compilation Dust emphasises surrealism, this one focuses on gore and violence. These were good times for Creation. In later years, a more apropos title would be Red Ink.

Here’s the problem. In 1933, Walt Disney adapted the classic tale of the Three Little Pigs into an animated short. It was an unexpected crossover success. Audiences loved the pigs, and loathed the wolf, who they saw as a symbol of the Depression. “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” became a national rallying cry. Disney made some other shorts starring these characters, but somehow they didn’t make the impact the original did. His verdict: “you can’t follow pigs with pigs.”

Here’s the problem. In 1933, Walt Disney adapted the classic tale of the Three Little Pigs into an animated short. It was an unexpected crossover success. Audiences loved the pigs, and loathed the wolf, who they saw as a symbol of the Depression. “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” became a national rallying cry. Disney made some other shorts starring these characters, but somehow they didn’t make the impact the original did. His verdict: “you can’t follow pigs with pigs.”

CS Lewis follows pigs with pigs here – or to be more exact, he follows pigs with a single half-sized runt of a pig that has mange, watery eyes, and a cracked hoof.

Why does this book exist? It’s not bad. It just doesn’t make a case that it ever needed to be written. Narnia is again under the yoke of oppression, and the Pevensie children have to save it. Usually when writers re-tell the same story, they up the stakes, often to the point where it becomes ridiculous (the Rocky series eventually had Sylvester Stallone going twelve rounds against international communism). Prince Caspian does the reverse, lower the stakes. Why?

This is a 5% milk version of TLTWATW . Queen Jadis was evil incarnate, King Miraz is a unmemorable fop. Once the fate of the world hung in the balance, now we’re resolving an dispute of Narnian regency. Exciting! Caspian never seems heroic or kingly – he does nothing except blow a horn and invite the Pevensies back to Narnia, where they immediately take over and virtually evict him from his own book. Even Lewis’s imagination fails to find cruise control mode: there’s no bits of whimsical imagery like the lamppost in the forest, or the faun with the umbrella.

It didn’t have to be this way. Prince Caspian could have been its own book, like the later Narnia titles. The hooks are all there. For example, we know the Pevensie children grew to adulthood in Narnia, before returning to their own world and their childhood bodies. How did this affect them? Apparently it didn’t. They still talk and act like upper middle class British schoolchildren. Why weren’t they transformed and left alien by their experiences? Why wasn’t their return to the human world marked by misbehavior and disassociation as they struggled to adapt? There’s so much material for a story here, so why did Lewis run a repeat?

There’s two great scenes in this book. The first is the early scenes between Caspian and Dr Cornelius – it’s exciting and well-paced, the way the conspiracy unfolds little by little. The second is the chapter “Sorcery and Sudden Vengeance”, where a disgruntled dwarf tries to overthrow Miraz by bringing the spirit of Jadis back. Unusually intense and almost diabolical – moments like this are why not all Christians are comfortable with Lewis’s subject matter. “No one hates better than me.”

Two exciting moments, that hint at Lewis stretching himself as a storyteller and a thinker. The rest of the book is like a musician working the scales. In a way, the title seems to refer to the book’s own stature. It’s a Prince, but TLTWATW remains the king, and it has no enchanted horn to blow.

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.

Is horror mangaka Junji Ito a real life Dorian Grey? He’s 52 years old, but looks younger than me. It’s as though the digits of his age imbibed cheap sake and switched position on a drunken dare.