Most stories have an endoskeleton: a theme that lies inside them like a set of bones. Sometimes it’s the same bones as another story: remove the flesh of plot from Lord of the Rings or Star Wars and you’ll find the skeleton of Campbell’s Heroic Journey. Autopsy a random romance novel from the 70s or 80s and the skeleton will be the Three R’s (Rebellion, Ruin, Redemption). Some stories are thin, their thematic skeleton close to the skin, while others are fat: you have to delve deeply through the narrative’s flesh, muscle and organs before you find it.

But then you have stories that have exoskeletons: their bones are on the outside. The theme sits on top of everything else: there’s no need to autopsy such a body to discover its skeleton, it’s there in plain view, and often it’s the only thing you see.

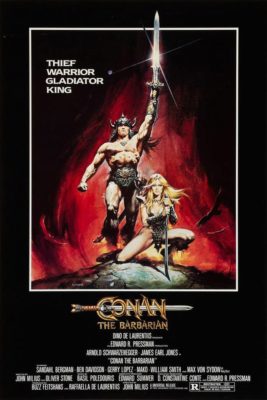

Conan the Barbarian is an exoskeletal movie, virtually all theme and zero story. Every character is an archetype, every plot point is as predictable as the movement of the stars, and the symbolism is very blunt – a Freudian psychoanalysist would suffer coronary thrombosis comparing swords to phalluses in this movie. It’s a stirring and powerful experience. Every scowl, drawn blade, and bombastic orchestral sting exists in service of myth. Conan the Barbarian is held high by mighty iron pillars of theme.

In ancient Hyboria, a tribe of Cimmerians is massacred by cultists of a dark snake god, and a blacksmith’s son is taken captive and sold into slavery. He grows to adulthood chained to a mill, revolving in endless circles. Somehow, this turns him into a muscular titan. Real slaves are skinny, haggard, and old before their time. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s body was clearly built by gym workouts, steroids and protein shakes. But that doesn’t matter, because the thematic through-line (“Conan has performed great labors and become mighty, that he might escape and seek vengeance against Thulsa Doom.”) vetoes logic and realism.

Conan the Barbarian is not faithful to any one Robert E Howard’s story (the Conan of this movie has more in common with Kull the Conqueror), but it’s faithful to Howard’s storytelling. It’s the sort of thing Howard would have written.

Howard, more so than the others of the “Weird Three” (Lovecraft and Smith) was indebted toward the lower side of pulp. He wrote action well, and his stories rely on energy and speed – they’re as streamlined as the mechanical rabbits that greyhounds chase. This also led to a certain carelessness. Lovecraft and Smith would carefully construct a setting: Howard threw up plywood constructs and then smashed them beneath stampeding Hyborian horses. Here’s what I mean:

Chunder Shan, entering his chamber, closed the door and went to his table. There he took the letter he had been writing and tore it to bits. Scarcely had he finished when he heard something drop softly onto the parapet adjacent to the window. He looked up to see a figure loom briefly against the stars, and then a man dropped lightly into the room. The light glinted on a long sheen of steel in his hand.

‘Shhhh!’ he warned. ‘Don’t make a noise, or I’ll send the devil a henchman!’

The governor checked his motion toward the sword on the table. He was within reach of the yard-long Zhaibar knife that glittered in the intruder’s fist, and he knew the desperate quickness of a hillman.

The invader was a tall man, at once strong and supple. He was dressed like a hillman, but his dark features and blazing blue eyes did not match his garb. Chunder Shan had never seen a man like him; he was not an Easterner, but some barbarian from the West. But his aspect was as untamed and formidable as any of the hairy tribesmen who haunt the hills of Ghulistan.

‘You come like a thief in the night,’ commented the governor, recovering some of his composure, although he remembered that there was no guard within call. Still, the hillman could not know that.

‘I climbed a bastion,’ snarled the intruder. ‘A guard thrust his head over the battlement in time for me to rap it with my knife-hilt.’

‘You are Conan?’

‘Who else? You sent word into the hills that you wished for me to come and parley with you. Well, by Crom, I’ve come! Keep away from that table or I’ll gut you.’

The setting is ancient, but the prose is modern. The dialog sounds like it’s from a hardboiled detective novel (you almost expect Chunder Shan to offer Conan $25 a day, plus expenses), and anachronisms like “the devil” and “parley” sit oddly in a tale of a vanished age.

For better or worse, this how the movie goes, too. Take away Conan’s mythic grandeur, and what’s left? “A rich man hires a tough to rescue his wayward daughter.” That’s a detective story. In fact, it’s the detective story. It’s the same basic plot as The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler and countless others. Everything beneath the exoskeleton is pure pulp.

Likewise, the movie captures Howard’s eclectic setting. Low-budget grindhouse films had a reputation for shooting with whatever props and costumes were available (leading to movies about roller-blading samurai, etc) and Howard’s stories have a similar feel. In The People of the Black Circle (quoted above) we get a weird amalgamation of real-world cultures, and Conan likewise throws together Mongols, Vikings, Indians, and everything in between. As Zack Stenz once pointed out, the movie owes quite a lot to 70s California beach culture. The story, written another way, could be phrased as “a Venice Beach bodybuilder and his hapa buddy do drugs, get laid, and fight a cult that exploits hippies.” Gerry Lopez (Subotai) was a surfer friend of director John Milius. Most of the remaining cast are athletes.

Some roles are oddly cast, but the most important one – that of Conan – is dead on. No role has ever suited Arnold more, except perhaps the Terminator. His overwhelming physicality sells him as a mightly-thewed barbarian, and his uncertain, rumbling, learning-to-talk diction adds verisimilitude. When you listen to Arnold speak, you don’t doubt that you’re hearing the beginnings of human language.

There are depths to Conan, but the surface is predictable. Its characters are so archetypal that they can’t do anything interesting or surprising. All of their motives are clearly spelled out, and the viewer is never in any doubt about what will happen – what must happen. Some movies are like taxis, slyly taking you on the scenic route through town if you’re not watching the meter. Conan is more like a train, pulling into the station, then leaving at a certain time on a fixed path. And since Conan is hardly the first film to adapt such mythic material, the train’s travelling down a route you’ve seen many times before.

But most people consider regularity in their form of transport to be virtue, not vice, and maybe the same is true for stories. For the rest of us, Conan the Barbarian’s the perfect movie to watch if you’re twelve, or want to remember being twelve.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.