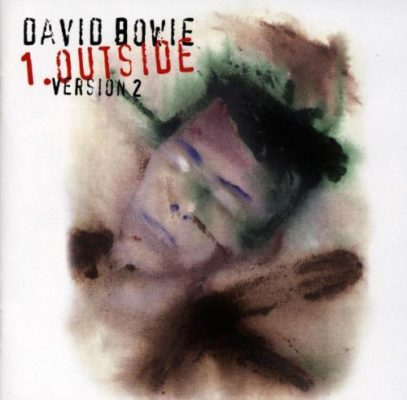

1. Outside is a masterpiece, Bowie’s greatest work in fifteen years, and barring a nanotechnological rebirth, will be his greatest work in the remaining sum of human years. (Sadly, I don’t believe Blackstar finishes as well as it began.)

But it’s exhausting. “Heroes” charges you up, this album drains you dry. The occasional pop song (“I Have Not Been to Oxford Town”, “Strangers When We Meet”) falls like a sweet berry between filth-stained cobblestones of industrial metal, avant-garde jazz, spoken-word interludes, and atonal ambiance. Sometimes the music seems to be reaching too far, and I feel I’m becoming lost. But when the next chord change hits, things always fall back into place.

Some parts I still don’t understand: in particular, the album concept. Something about ritualistic human sacrifice, a private detective, and characters called things like Algeria Touchshriek and Leon Blank. References are made to the “world wide Internet”, and Richard Preston’s alarming 1994 nonfiction book The Hot Zone. Something seems to have happened to this world, an event that Bowie won’t allow us to know. We’re peering through the window, guessing. We’re outside.

Maybe there’s not even a single concept. Like Diamond Dogs, Outside is a musical patchwork quilt, assembled from the wrack of a few different projects. In 1994, Q Magazine asked him for a “week in the life” type diary. Bowie felt that his real life wasn’t quite as exiting as they were probably hoping, so he wrote a fake diary by one Nathan Adler (this diary is reprinted in Outside’s liner notes). Two years earlier, he’d re-united with Brian Eno, and attempted to form a kind of avant-garde supergroup (much of their work eventually saw release on the internet as the Leon Suite.)

In addition to Eno, Bowie has his most powerful lineup in years. Carlos Alomar is back (holy shit!), as is Reeve Gabrels, whose rhythm tracks are distorted to near Static-X levels. Mike Garson makes a very welcome appearance – if you liked the middle fifty-five bars of “Aladdin Sane”, Bowie just gives him six kilometers of rope on this album. He just lays down solo after solo, on track after track, shredding Bowie’s chord progressions with hailstorms of chromatic notes.

The internet, or “information superhighway” (as it was ponderously called in 1995) is a big influence here. Outside seems married to it, somehow. Here’s a David Bowie FAQ from 1996 or so: it’s interesting to read Bowie’s fascination with computers (the digital art accompanying the Q Magazine story was created by him, somehow). Soon BowieNet would exist.

Picking out great tracks is hard, but I really like four. They come in groups of two, each positioned next to each other on the tracklisting (ignoring a segue).

“A Small Plot of Land” is aggressive, ear-bleeding jazz, paying tribute to Scott Walker and nearly upstaging him. “Hallo Spaceboy” is an industrial dance experiment that makes “Pallas Athena” sound like “All of the Dudes”. “Thru’ These Architects’ Eyes” riffs of Thomas Aquinas’s idea of God being an architect, and takes the album to new, celestial heights. And closing track “Strangers When We Meet” is powerful, dark, and tuneful. A perfect song to end on.

Some Bowie albums are best without their context. Outside is best with it. It’s flotsam from a confused and turbulent time in human’s history, when zero started to became one. Bowie was much better than average at predicting the future, but here we see him caught up amidst manifesting predictions – society unease and turmoil, and a digital pantokrator set to pave over humanity with silicon wafer. The album was meant to have a sequel, called Inside. This never materialised, but the wheels of time still turn, and soon we will see Inside for itself.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.