The events of the future are unknown, but The Future is an old friend: we’ve seen it come and go before.

First, new horizons appear. The lookout in the ship’s crow’s nest sights a new continent. Astronauts witness the dark side of the moon. But then the horizons blacken. The new continent is despoiled and pillaged. The moon asks the astronauts “you’re here. Now what?” The unknown turns ugly very quickly, as a piece of paper burns from the edges in.

A theme in science fiction (emphasized in the New Wave of the 1970s) is that we might not know what to do with the discoveries of the future: that our wings will burn away, and then we’ll fall. Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey took a less (or perhaps more) pessimistic approach, the future will change us so that we cannot fall. Evolution will alchemize us: the primitive shaggy apes are doomed, and though their descendants will succeed in the new world, they are not their descendants. Will we live or die in the future? Maybe it’s not simple. Maybe we’ll be different.

David Bowie saw the film while stoned, and it excited him terribly (interesting coincidence: the astronaut in the film is called “Dave Bowman”). His career was bouncing along like a dead cat at the time – failed bands, a dead-on-arrival album in 1967, and no real musical identity. His manager Ken Pitt was wearily cobbling together a promotional film (the unreleased Love You Till Tuesday), and he needed a filler track. Bowie wrote “Space Oddity”.

Forty four years later, it is Bowie’s signature song. It was performed in space by Chris Hadfield, four hundred kilometers above the earth’s surface. Unlike the apes, the humans, and Bowie himself, “Space Oddity” might never die. It has been selected for quasi-immortality. Nothing about the song makes sense. It’s a filler that will live forever; a tonally complex piece (with fifteen different chords) that can be strummed in basic outline by any starting guitarist; a musically indecisive song (neither sounding like folk or rock) that captures an era and a career. I’m still not sure what to make of it, but clearly we have to make something. It will outlive us, too.

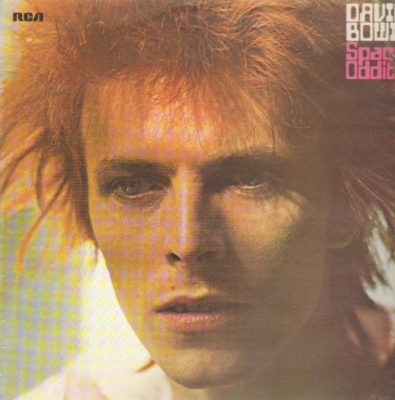

The song’s minor success upon release (it was used by the BBC to score footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing – nobody seems to have realised that the song ends with the astronaut stranded in space!) led to a rushed album, initially self-titled, then rebranded as Space Oddity.

It’s not an unreserved classic. It’s confused at times, as if part of it still exists in imagination, and was imperfectly drawn into reality. The songs are mostly longwinded and complex, and the band doesn’t sound as tight as it needs to be. Tony Visconti’s solution was to slather everything in reverb and room noise, leaving Bowie’s vocal track to hold things together.

Although there’s only one outright bad song – the hideous “God Knows I’m Good” – it’s a frustrating listen at times, sometimes underdeveloped, and sometimes over-egged. Tracks like “Letter to Hermione” are so thin they can hardly stand upright, while “Unwashed and Somewhat Dazed” and “Cygnet Committee” struggle not to collapse under their weight. I want to run a butter knife over it, and smooth all the clumpy parts.

But Space Oddity is obviously a start for him. You can see where “Cygnet Committee” ends and “Savior Machine” begins, for example. There’s moments of real artistry: “Memory of a Free Festival” begins as a pile of indistinct musical fog, and just when you’re good and lost, a ship’s prow pierces the mist. You can hear the song make sense of its own confusion, and it’s one of the finer moments of the album. The album’s lyrics are mostly confessional in nature, which isn’t something we saw a lot of before or after. A lot of it’s about disillusionment. “Letter to Hermione,” “Cygnet Committee”, and “Wild-Eyed Boy from Freecloud” are kiss-offs to various relationships and social cliques Bowie was a part of.

Although it lives in the shadow of its very famous track, there’s much of interest here. I would not recommend this as a first Bowie album for anyone, and it might be best as their last: when one’s deep enough in the game to wonder where he came from and how he got to the present. If you want evolutionary steps, this is where we see vestigial legs appearing on Bowie. It’s very spacey, very odd, and very worthwhile.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.