The eye sees by transmitting light from the retina to the optic nerve, and then to the brain. The problem is, the optic nerve runs in front of the retina itself, blocking a sliver of light. In order to see, you must have a blind spot.

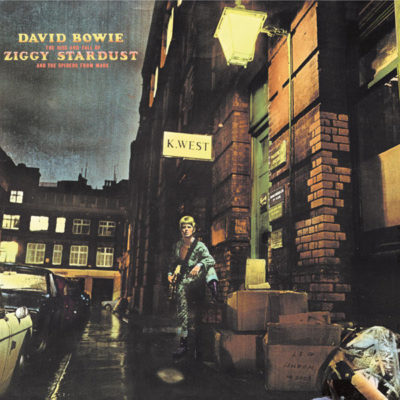

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is my blind spot. It’s the only Bowie album I like and yet don’t “get”. Musically, it has some of his best work. Conceptually, all the stuff about fake rockstars and androgyny and the world ending in five years seems bizarre and unnecessary, like you’ve invited a friend to stay the night and he’s brought along a U-haul full of childhood toys. It must have struck a nerve (optical or otherwise) at the time: Ziggy Stardust launched his career. But in the 21st century, he’s shadowboxing at targets I cannot see.

Not only did Ziggy not need to be a concept album, maybe it wasn’t meant to be one. It’s rock and roll’s dirty secret that most “concept albums” are retroactively branded as such long after the album is finished (the most famous one, Sgt Pepper, has no concept at all that I can detect). It’s true that many (or perhaps most) of Ziggy Stardust‘s songs don’t tie back into the main story, and the ones that do are jumbled out of order. The most persistent through-line is that Bowie likes writing songs with the word “star” in the title.

The album helped put glam rock on the map, but it’s also a preview screening of Young Americans: lots of soul and jazz moments pop up, sometimes improving the album and sometimes detracting from it. “Five Years” and “Soul Love” are a bit too long and musically subdued to work as album openers, particularly in the second case, where the dominant instruments are hi-hats and congas. “Moonage Daydream” is the first legitimately great song, with a bombastic introduction and a hallucinatory chorus. “Starman” is charming and irresistible, and sounds very much like a song left over from the Hunky Dory sessions.

Unlike the front-loaded Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust‘s best moments happen on side B. “Lady Stardust” is an powerful piano ballad, “Hold on to Yourself” an energetic homage to Ed Cochran’s “Somethin’ Else”, and “Ziggy Stardust” sports an instantly memorable main riff, built around a minor 2nd hammer-on with the pinkie finger. Bowie would work with more skilled guitarists than Mick Ronson, but few if any had his taste and discernment. Every note Mick played meant something.

“Suffragette City” is the album’s greatest song, a fierce and pummeling broadside against the Rolling Stones. While “Starman” points to his past, this points to his future: it would have fit anywhere and everywhere on Aladdin Sane. “John, I’m Only Dancing” is a nice curate’s egg if you have the Rykodisc remaster, with a strong chorus and funny queerbaiting lyrics, although I prefer the cut from 1973.

No doubt Bowie-ologists find more in Ziggy Stardust‘s concept than I have, whether it actually exists or not. Take the name “Ziggy”, a strikingly unusual name that would be worth 19 points if it could be played in Scrabble and seems pregnant with meaning. Is it an abbreviation of “syzygy” (a planetary conjunction or apposition, which would reinforce the cosmic theme)? But David eventually admitted that it meant nothing. He just wanted a name that began with Z, and found one in a list of names.

But Bowie was always someone who could turn pewter into gold, and even unremarkable ideas can seem irresistibly clever if sold right, which in the end is the rockstar’s true calling. Ziggy Stardust deserves its place at Bowie’s masked ball, even if that place isn’t quite at the head of the table.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.