“O liberty! What crimes are committed in thy name!”—former revolutionary Marie-Jeanne ‘Manon’ Roland de la Platière, as she was led to the scaffold

The Ancien Régime imprisoned people. The First Republic imprisoned other, different people. The Napoleonic Empire imprisoned still different people. Marquis de Sade achieved the singular feat of being imprisoned by all three.

The ancient alchemists theorized in the existence of ignis gehennae, or universal solvent. Sade was a universal convict. Anathema to all creeds, curse on all lips, breach of all laws written and unwritten; he increasingly seems made-up: a boogeyman for thought experiments.

“Oh, you think your hypothetical utopian society is hot shit? Well, suppose Sade comes along…”

His books are grotesque nightmares, and his real life frequently matched them. Even by the low standards of the 18th century French gentry, Sade was a depraved human being, wretched down to his bones. There are probably no good answers to “why did you torture that prostitute?” but “Which of several prostitutes are you referring to?” seems like a particularly bad one.

At least he had amibtion. I watched a TV documentary on Jared Fogle, and found it a dismaying exercise in Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. He was dull and drab and spiritually small. A pallid white lump, his face perforated by a horrible toothy little smile, existing like a smear of phlegm that I couldn’t wipe off my screen. He seemed bled dry of anything hale and human; a monster made of skim milk and tofu. Can’t the twentyworst century produce better bad guys than fucking Fogle?

The Marquis dreamed big dreams. His crimes (both fictional and otherwise) have a bloody, artistic grandeur. He was a Matisse of Misery, a Picasso of Pain. I’d prefer it if neither Sade nor Fogle existed, but if I had to choose one or the other, hail Sade.

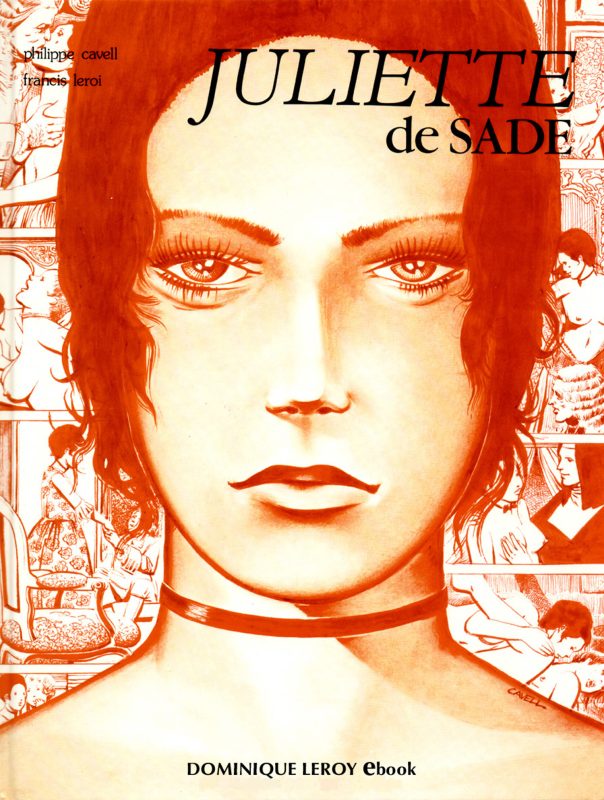

Juliette (1797) is a sister book (literally) of his earlier Justine (1987). They describe the adventures of two destitute young women who seek their fortunes in Paris, taking different paths, and experiencing different outcomes.

Justine is saintly and pure and devoted to virtue. She is repaid with beatings, rapes, and degradations. Nature abhors goodness, a subtext made crystal-clear in the book’s final scene. Justine is finally rescued from a life of torture by her sister…and then a bolt of lightning strikes her down.

Juliette, meanwhile, is a sociopathic harlot who sins her way upward into the highest echelons of society. What’s interesting is how her character changed with time. In Justine (which Sade wrote inside the Bastille), she’s an opportunistic chancer who commits crimes out of necessity, rather than choice. She might still be able to redeem herself, and at the book’s end she appears to do so by (humorously) becoming a nun.

Madame de Lorsange [Juliette’s title – ed] left the house at once, ordered a carriage to be made ready, took some small provision of her money with her, leaving the rest for Monsieur de Corville to whom she gave directions concerning pious bequests to be made, and drove in haste to Paris where she entered the Carmelite Convent there. Within the space of a few years, she had become its model and example, known not only for her deep piety but also for the serenity of her spirit and the unimpeachable propriety of her morals

But in Juliette (written when Sade was free), she’s portrayed as comically evil and disgusting. She murders a lot of people, participates in a plot to cause a famine in France, and has sex with about five to ten thousand men, including the pope. She’s Messalina, Lucrezia Borgia, and Jeffrey Dahmer rolled into one—a character so ridiculous that she’s kind of funny.

The Justine/Juliette diptych mixes styles and affects. First, it’s porn. Second, it’s parody, mainly of romance “manners” fiction and books like Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie. Third, it is an exposition of Sade’s worldview and philosophy: good is stupid, morality is stupid, and the purpose of life is to drench your hippocampus in pleasure, no matter who suffers for it.

“Before you were born, you were nothing more than an indistinguishable lump of unformed matter. After death, you simply will return to that nebulous state. You are going to become the raw material out of which new beings will be fashioned. Will there be pain in this natural process? No! Pleasure? No! Now, is there anything frightening in this? Certainly not! And yet, people sacrifice pleasure on earth in the hope that pain will be avoided in an after-life. The fools don’t realize that, after death, pain and pleasure cannot exist: there is only the sensationless state of cosmic anonymity: therefore, the rule of life should be … to enjoy oneself!”

Sade viewed pleasure like rays of sunlight gathered by a lens. The more rays are focused by the lens, the more it burns and destroys the ground beneath. If you want to know pleasure, you have to be prepared to know (and inflict) pain. Sade was a living Pyreliophorus, a colossal burning glass that incinerated everything it touched. Nobody (except maybe Ayn Rand) was ever such a dark, living embodiment of their own philosophy.

Juliette is a better book than Justine. The main character controls her fate, instead of being a punching bag. Sade has a troubled relationship with feminists (in the sense that fire has a troubled relationshp with TNT), so it’d be ironic if he created possibly the most agentic female character in all of 18th century literature. As surrealist writer Guillame Apollionaire once said:

“The Marquis de Sade, that freest of spirits to have lived so far, had ideas of his own on the subject of woman: he wanted her to be as free as man. Out of these ideas—they will come through some day—grew a dual novel, Justine and Juliette. It was not by accident the Marquis chose heroines and not heroes. Justine is woman as she has been hitherto, enslaved, miserable and less than human; her opposite, Juliette represents the woman whose advent he anticipated, a figure of whom minds have as yet no conception, who is arising out of mankind, who shall have wings, and who shall renew the world.”

And if you want nastiness, Justine‘s horrors are limited by the fact that the heroine must survive her abuses (although it’s still implausible that she doesn’t die at certain points), but because Juliette is the perpetuator, not the victim, and the gloves can come further off.

Juliette also shares many of Justine’s flaws. For one thing, it’s incredibly long—my English Austryn Wainhouse translation is about 450,000 words. There’s just too much book in this book.

For another, Juliette’s conflicting goals—satire, versus philosophical treatise—weaken each other. Often it’s not clear how serious he is. Are Sade’s endless rants (delivered through the mouth of some character or another) meant to be funny, or not?

“Before going farther, let us here observe that nothing is commoner than to make the grave mistake of identifying the real existence of bodies that are external to us with the objective existence of the perceptions that are inside our minds. Our very perceptions themselves are distinct from ourselves, and are also distinct from one another, if it be upon present objects they bear and upon their relations and the relations of these relations. They are thoughts when it is of absent things they afford us images; when they afford us images of objects which are within us, they are ideas. However, all these things are but our being’s modalities and ways of existing; and all these things are no more distinct from one another, or from ourselves, than the extension, mass, shape, color, and motion of a body are from that body. Subsequently, they necessarily…” [blah blah blah for another thousand words]

These ludicrous speeches are inserted in inappropriate places, frequently run for multiple pages, and stop the novel in its tracks like a bolt-gun to a calf’s brain. Eventually you just stop reading them—you see an ominous mass of text hanging on the page like a stormcloud, and skip it. They are pointless.

Is he convincing anyone? He could have written “feels good bro” and then found a more stimulating use for his wrist. The longer and louder you have to argue for something the less persuasive it seems. If libertinism is truly natural and right, he shouldn’t need to justify himself so much. He sounds like a lawyer bolstering a weak case. What would a psychiatrist make of Sade’s psyche? Did he know, deep down, that there was something pathological about him? In other words, who’s this justification for—us, or himself? “I’m normal! I’m normal!” is the battle cry of the person who’s absolutely not normal, and Sade’s appeals to universal human nature fall flat. His inhumanity was deeply unnatural.

(Incidentally, my favorite piece of Sade trivia is that they performed phrenology on him after he died. His skull was the perfect shape for a priest.)

Digressions aside, Juliette is an endless list of sins and outrages, mostly involving sex and blasphemy. It reminds me of those 90s porn videos series, where they go on and on, until you have Barnyard Sex Adventures #45 or something. It’s a long series of repetitive fantasies, unvarying in tone and content, delivered with the obsessive rhythm of an autistic child’s stimming.

Juliette’s endless escapades eventually provoke boredom, and then a coma. The book basically starts at self-parody and goes on from there. “Juliette gets buggered by a million trillion men while spitting on a cross while stepping on orphaned puppies”…much of the book is simply a permutation on that.

Yet Sade can actually write affectingly (and disturbingly) when he wants to. I enjoyed the moments where he transcends himself, and offers up something incalescently disgusting.

A dim, a lugubrious lamp hung in the middle of the room whose vaults were likewise covered with dismal appurtenances; various instruments of torture were scattered here and there, among other objects one saw a most unusual wheel. It revolved inside a drum, the inner surface of which was studded with steel spikes; the victim, bent in an arc upon the circumference of the wheel, would, as it turned, be rent everywhere by the fixed spikes; by means of a spring device the drum could be tightened, so that, as the spikes grated flesh away, they could be brought closer and contact with the diminished mass maintained. This torture was the more horrible in as much as it was exceedingly gradual, and the victim might well endure ten hours of slow and appalling agony before giving up the ghost. To accelerate or slow the procedure one had but to decrease or widen the distance between the wheel and the compassing drum

Sade had a gift for devising tortures. It’s lucky his relative poverty forced him to keep most of them on the page.

There’s also some parts where he anticipates the decadents, too, particularly a passage that will stay with me for a long time. It’s where Sade basically abandons any attempt at “manners” literature, and starts writing pure fantasy.

Juliette and a few consorts have journeyed deep into Russia. It’s portrayed as a blackened land of volcanoes that spit blue-white fire. Juliette throws a match onto a field. It erupts into flame.

In this improbable landscape, they encounter a literal fairytale giant. “Seven feet and three inches tall, with, behind huge moustaches, a face both swarthy and awful.”

This is Minski, a Russian lord who has established a fiefdom in this harsh land, mostly because it’s a place where the law does not exist.

The giant stoops and lifts a great stone slab no one else would have been able to budge; thus does he uncover a stairway; we precede him down the steps, he replaces the stone; at the farther end of that underground passage we ascend another stairway, guarded by another such stone as I have just spoken of, and emerge from dank darkness into a lowceilinged hall. It was decorated, littered with skeletons; there were benches fashioned of human bones and wherever one trod it was upon skulls; we fancied we heard moans coming from remote cellars; and we were shortly informed that the dungeons containing this monster’s victims were situated in the vaults underneath this hall.

Minski devours the dead bodies of children at his table, which is made from naked girls arranged and twisted together (the chairs and candelabra of his dining hall are likewise made of living nymphets.) Sade really delivers some perverted weirdness here. His descriptions of the giant’s appetites and behaviors are gruesomely earthy. It’s no less unrealistic than anything else in the book—just pure limbic system horror that engages the senses rather than the intellect.

Minski takes a shine to Juliette, and allows her to live and witness his lifestyle (most of her companions are…less fortunate). She soon participates in his barbaric sex-murders. Yet she senses that the giant’s favor will prove a fleeting thing, so she incapacitates him with a near-lethal dose of stramonium, and escapes. She doesn’t kill him, though. A man as evil as Minski doesn’t come along every day, and it’d be a shame to lose him.

So that’s Sade: he’s endless, repetitive, as sadistic to his readers as he is to his characters, and occasionally offers up brilliant visions. So what do we make of him?

A criminal, as I’ve said. Even death didn’t clear his name. His books were banned in France for over a hundred and sixty years. People were prosecuted for selling them in the nineteen-fifties. They were mass-burned in America. For a while, you could acquire yellowcake uranium more easily than one Sade’s books.

His extreme fantasies were clearly and disturbingly connected with real things. There is his real-life crimes to consider. Libertinism was no joke for Sade, no ironic pose. He tried to practice what he preached. Most “edgy” writers are smoke without fire. Marquis de Sade wasn’t just fire, he was thermonuclear plasma.

But even his writing, viewed in isolation, seems to hit a cultural nerve. Inside every priest is a hypocrite, and in every king a tyrant. Thrones are edifices raised atop conspiracy and filicide. “Self-made” men become rich by exploiting those under them. Goodness is a mask for sociopaths too clever to get caught. And the concept of virtue is worse than false: it is a psychosexual weapon wielded to make others (particularly women) easy to control. You should take pleasure wherever you find them. The only law is that there is none. And so on.

All of of this formed the bedrock of the Sadean worldview. Some find it true. Others find it revolting. Still others find it both things. Nobody finds it ignorable or trivial.

Sade’s words leave a shadow in the mind. His bizarre pornographic fantasies are littered with allusions to Hobbes, and Malthus. He presages Darwin, Haeckel, Lamarcke, Hitler. He was an atheist, yet revered nature’s impulses with fanatical zeal. Indeed, he thought they were the only real thing, and human institutions were just thin froth riding atop a dark and deep ocean.

Maybe we hated him because he told the truth? Sade was born in a palace and died in an insane asylum. Perhaps his main observation was that the two places are very much alike.

“Imperious, choleric, irascible, extreme in everything, with a dissolute imagination the like of which has never been seen, atheistic to the point of fanaticism, there you have me in a nutshell, and kill me again or take me as I am, for I shall not change.”

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.