Max Headroom is a “computer animated” TV host from the 1985 UK music video series The Max Headroom Show, the 1985 telemovie Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future, and the 1987 science fiction series Max Headroom.

Air quotes because he’s not computer animated, he’s actor Matt Frewer with latex and foam stuck to his face. Computer animation cost tens of thousands of dollars per minute in 1985, and Victorian chimney-sweeper logic kicked in: “screw cutting edge technology, let’s send an eight-year-old boy up the flue.” In 2020, computers steal jobs from humans. In Max Headroom‘s time, we stole jobs from them.

Max’s character is jarring and wrong, st-st-stuttering like a stroke victim as he reels of Dangerfield-esque one-liners. The idea is that he’s a human consciousness digitized imperfectly – a half-a-human. You can’t be at ease while watching him, it’s like eating dinner off a cracked plate. The fact that he was broken ironically made him complete: nobody would remember his unfunny jokes if they’d been delivered in a normal voice. He’s a vivid example of glitching and ugliness used for artistic effect (note the similar stuttering used in Paul Hardcastle’s “19”).

Max is a one-idea character, but the idea proved highly successful. He’s widely recognized (and parodied). There’s a Hello Kitty aspect to Max: everyone recognizes the character, but few can tell you where he’s from, or even where they first saw him. For some, it was the New Coke commercial; for others, Max Headroom just exists, a creation without a creator, floating freely in conceptual ether.

The character, however, emerged out of a very specific set of circumstances.

In 1981, video killed the radio star, and stations such as MTV needed hosts to talk between records (where “talk” means “sell products”). Unlike radio hosts (who were heard but not seen), video jockeys needed to look attractive, or at least interesting in some way. They couldn’t, for example, be a man “shaped like whatever container you pour him into” (in Patrice O’Neal’s immortal roast of chubby radio host Jim Norton).

Most stations wanted their hosts to be hip, the UK’s Channel 4 took a different path and made their host a weird, uncool goober, whose lame one-liners are further mangled by a layer of digital distortion.

It was a great idea: Max Headroom won’t ever become lame: he’s already maximally lame. He won’t lose dignity when he plugs a sponsored product: he had no dignity to begin with. Rock stars will want to talk to him: he’ll made even the most incompetent cokehead seem like a scholar.

But Max Headroom didn’t become famous from the music video show.

It soon occurred to Channel 4 that this character might work in a sci-fi drama, and the result is a dated but interesting cyberpunk film that owes a lot to Blade Runner and Brazil, although made for far less money.

The film is set in near-future England, which could be described as “Thatcher, but more”. London is as black and filthy as the inside of a tar-saturated lung. Thugs lurk in the shadows, ready to kidnap you and sell your organs to body banks. Industry is ferocious, a terrifying machine running on a fuel of human lives. There are televisions everywhere, blaring idiocy.

The plot involves entertainment conglomerate Channel 23, who have invented a new form of TV ad called the “Blipvert”. Traditional 30-second ads annoy viewers and cause them to change the channel, but Blipverts allow ads to be compressed into a few seconds of high-intensity audiovisual stimulation. Ratings are through the roof. However, some people experience a side effect: they explode.

There’s some funny and effective satire where we see Channel 23 execs trying to defend Blipverts. No causal link has been proven! Surely some percentage of the population can be expected to randomly explode, right? Also, if you explode after watching an ad, isn’t it your fault in the end? We’re probably supposed to think of tobacco companies: modern viewers will think of the oil industry.

Regardless, star reporter Edison Carter (who works for Channel 23 himself) gets “too close to the truth” and suffers a tragic motorcycle “accident”. However, he’s supposed to appear on air later that day, and a bungled attempt to digitize Carter’s brain results in an odd lifeform that immediately utters the words “Max Headroom”, because that was the final thing Carter saw before his bike crashed.

Writer George Stone says British firms spent millions of pounds relabeling the “Max Headroom” signs in public garages to “Maximum Height”, due to association with the character. There’s a slight chance that Max Headroom actually cost Britain more money than it made.

The movie did not really have a budget. Its portrayal of futuristic London as an industrial wasteland is more a concession to lack of money than anything (in a stroke of luck, they were able to shoot in Beckton Gasworks, where Stanley Kubrick filmed certain scenes in Full Metal Jacket).

Yet it nails the things that are cheap: acting, and tone. A grungy and effective mood soon appears. The story’s confusing and hard to follow, but it’s not boring.

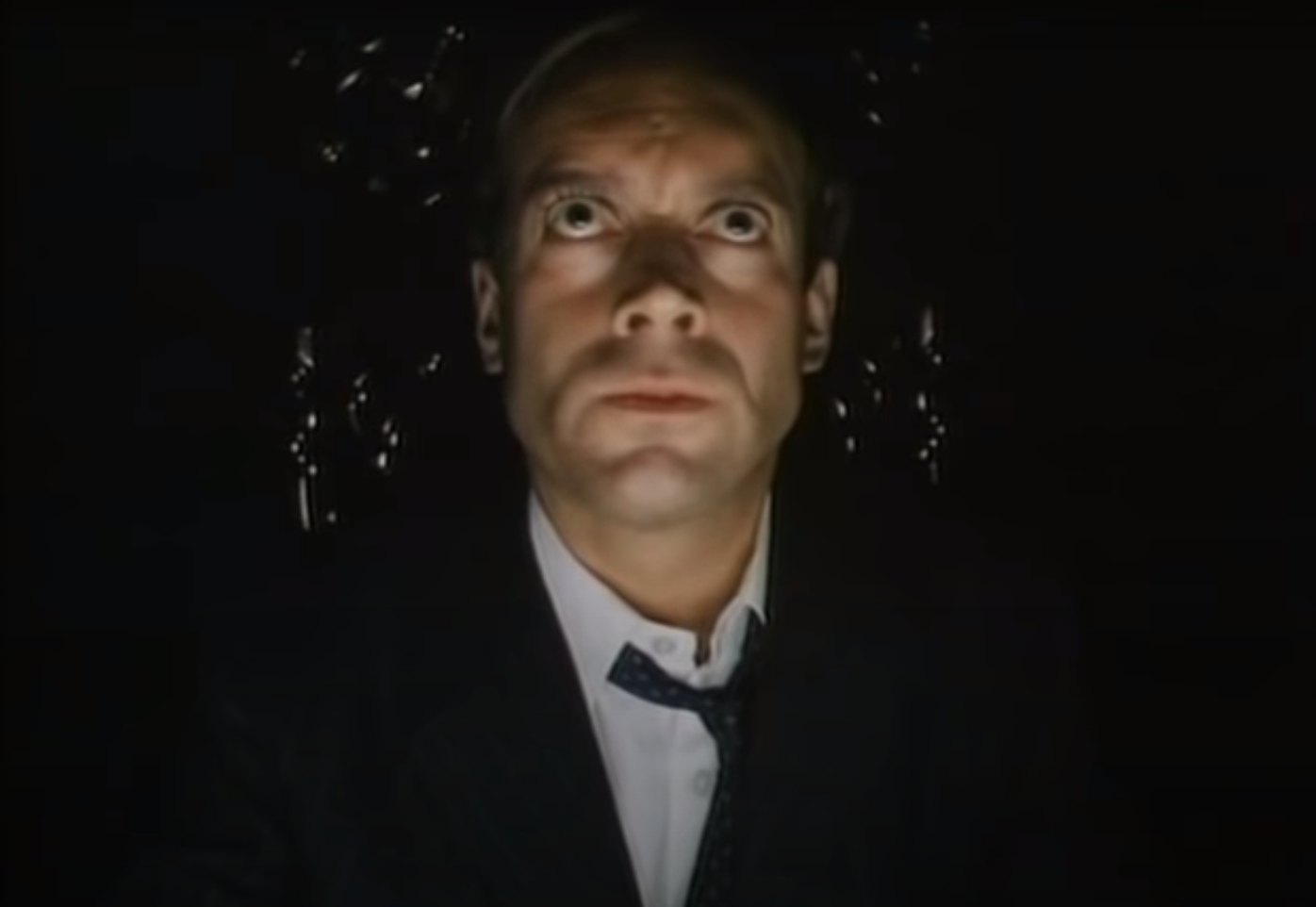

The camera-work has an aggressive, edge-pushing quality that’s as unsettling as Max Headroom himself. For example, consider the alarming way the villainous Channel 23 head Grossman is framed. Sharply underlit, and distorted by bubbled lensing in a way that emphasises actor Nickolas Grace’s exotropia. He looks terrifying, a one-man Panopticon.

Max Headroom actually doesn’t do much in this movie. The same holds true for the American TV series: the episodes explore some science fiction conceit related to capitalism and media (a reality TV show is attracting viewers through subliminal mind control, or something), and Max serves as a framing device for the story. He’s Tel-vira, Maxtress of the Byte. But isn’t that what a VJ is supposed to do? Introduce stuff, and get out of the way?

People like Edison Carter and Theora got to have all the fun, running around and solving crimes. Max is just a talking head, frozen in place, transfixed like a glitching, jittery butterfly upon a technological pin.

He has nothing to do. He just tells his idiotic jokes and becomes more outdated day by day. Matt Frewer was wont to complain about how annoying his makeup and prosthetics were (“like being on the inside of a giant tennis ball”), but the character itself was just as restricted.

Video hosts are passive, powerless ciphers, introducing the action without ever being a part of it. They’re like eunuchs guarding the sultan’s harem – yes, they know all about the deed, but they’ll never do it for themselves. It’s no surprise that the career breeds dissatisfaction, and a search for something more.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.