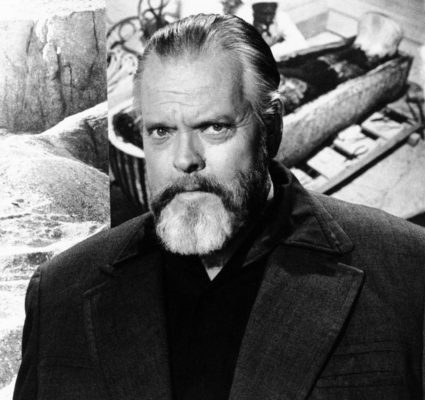

In 1938 Orson Welles directed Citizen Kane, often cited as the greatest movie of all time. As Roger Ebert said, not everyone agrees that Citizen Kane is the best film, but the dissenters can’t agree on a film to replace it.

His subsequent career was a skyrocket, ie, it spent most of its trajectory going down.

His later films were largely financial failures and soon stopped having finances to fail with; 1942’s The Magnificent Ambersons grossed $1 million on a $1.1 million budget, and 1948’s Macbeth was made for $800,000 but never saw wide release.

Welles spent the latter part of his life as professional box office poison, self-financing his films through residuals and bit parts. He’d become (vide Scott Walker) a man everyone wanted to know and nobody wanted to write a check to. Critical reaction to his films was also cooling: you can read contemporary critics struggling with his work, giving it shot after shot, but only because the director had made Citizen Kane.

Ebert’s review of Othello reads like a mechanic detailing a car: he explains its ins and outs and production hurdles and obscure details about the set design…and you still have no idea whether he likes it or not. Except that you do: when a critic reviews a Great Director(tm), silence means something.

Gregory: “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Holmes: “That was the curious incident.”

In 1945, Welles was given a column at the Washington Post. For $350 a week he produced freewheeling, unfocused, unreadable scandal columns containing insular Hollywood gossip, some of which were potentially libelous (“the fascist salute was invented by the Hollywood film director C.B. DeMille”). The column lasted one year, and became an early example of how the formula of famous person + massive platform simply cannot fail to fail to fail.

Orson Welles ended his career the way he’d begun it: using his voice to sell things. In 1970, an advertising agency tapped him to record ads for various consumer goods, and in case he thought he still had dignity to lose, they made him audition for the part.

“An ad agency called and asked me to do a voice over. I said I would. Then they said would I please come in and audition. ‘Audition?’ I said. ‘Surely to God there’s someone in your little agency who knows what my voice sounds like?’ Well, they said they knew my voice but it was for the client. So I went in. I wanted the money, I was trying to finish Chimes at Midnight.”

The frozen pea ad is notorious. Even to this day, it has a cringeworthy aura to rival LEAVE BRITNEY ALONE and so on. Orson Welles is visibly irritable and quibbles with his director about his lines and how he’s to say them. It feels like satire. The magisterial, stentorian voice that used to orate Shakespeare is selling frozen goods for money. The peas aren’t the only thing on ice.

In the Youtube era these ads went viral yet again. “We Will Sell No Wine Before Its Time” has probably been viewed more times than any of Welles’ actual films, save Citizen Kane. Welles slurs incomprehensibly. I doubt the vineyard had any wine left: he appears to have drunk their entire stock to numb the pain.

On one level, it’s upsetting to see Welles reduced to this, the bones of a prize horse melted to glue. It’s also jarring to see the reality behind the curtain of the TV ad world. I dunno – on some level, we still believe that Santa is real, that pro wrestling isn’t fake, and that the guys on TV mean what they say.

These are sad tapes, but they’re also happy ones. Welles was washed up at the end of his life…but is that such a bad thing? Being washed up means you were once in the water. Most people spend their lives on the shore.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.