Quarxs is an early computer-animated TV show from 1990. It was produced three years before VeggieTales and Insektors, four years before ReBoot, five years before Toy Story, and thirty-two years before Morbius.

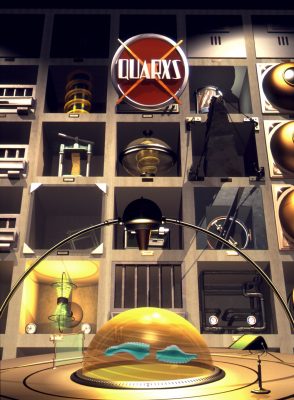

Created by digital artist Maurice Benayoun, it’s a fake documentary showcasing imaginary lifeforms called Quarxs. They have a strange relationship with space and time, and their behavior in the physical world is peculiar. For example, the Elasto-fragmentoplast wraps around small curved objects and smashes them, while also turning liquids into solids. The Spiro Thermophage lives in pipes and causes hot water to flow faster than cold water. And so on.

Basically, the Quarxs are gods of the gaps. Everything confusing about our universe (from dark matter to the missing socks in tumble-dryer) is directly or indirectly caused by them. The show consists of a rambling Attenborough-style scientist capturing Quarxs and putting them in a cage and demonstrating what they do. Then there are credits.

If this sounds like a total waste of time, well, don’t say I didn’t warn you. Quarxs is basically an art demo for a nascent medium (computer graphics). It was supposed to wow people at SIGGRAPH demos and get cited in post-predeconstructive media studies journals. It was not supposed to be particularly compelling TV.

You have to force your head into a weird space to enjoy it. Think how an abandoned internet message board from 1999 feels. Empty, irrelevent, superseded, and chanting with an eerie, hypnotic aura, as though its sheer deadness gives it power. That’s the space where Quarxs lives and dies.

The media landscape of 1990 was different in ways that barely make sense now. Battle-lines were drawn up and fought over digital art – even whether the concept could exist. Computers were regarded by artists as business tools – “computer generated art” made as little sense as “cash register generated art”. One of the challenges for historians of computer-generated art is that many rejected the title.

Quarxs had a hard row to hoe. There were no TV shows like it, and few precedents in the art world, either. It’s one of the founding examples of digital art, along with Frank O. Gehry and Heath Bunting. It’s a piece in a puzzle that’s been solved for so long that it’s hard to believe that there was once nothing here, just a blank space.

(Fans of classic gaming will remember a similar shift happening at the same time. PC games in the 80s were branded as “intellectual” fare: meaning flight simulators and CRPGs and text adventures. Action was the domain of consoles. Then, within a few years, a flurry of fast-paced action games for DOS shattered that preconception: Commander Keen, Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, and Prince of Persia. “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen” – Lenin)

To be sure, CGI was limited in 1990, which cramps Benayoun’s visions greatly. Half the time, the determining factor in a given Quarxs’ abilities is “can we animate this on a SGI IRIS with 2MB of memory, y/n”? The Elasto-fragmentoplast turns liquids into solids. Why? Mostly because it saves the animators from having to render fluid physics, which would have been a pipe dream in 1990. Unlike Steve Speer’s (probably even more groundbreaking) short “The Only Taste Is Salt”, the show consists of short and simple camera movements, and there are no human characters.

There’s some entertainment value. The narrator of the show (a self-described “esteemed cryptobiologist”) is obviously quite insane, and makes frequent references to some unknown people (or things?) persecuting him for his views. His explanations of the Quarxs are questionable but hilarious. Why does the Elasto-fragmentoplast pursue rounded objects? Because, as a male, it has a fetish for curves.

Benayoun seems to be laughing at the conservatism of traditional media artists. Near the end of the show a new species of Quarx is discovered, the Mnemochrome, that vandalizes priceless works of art by swapping bits of them in and out of each other (with a prominent digital scanline effect). The narrator has an aneurism.”Good heavens! They have no respect for anything!”

Is it true? Is technology the end of art? Probably only to the extent that it’s the end of everything. Evolution is a ladder seemingly without an end: no creature can command the top forever. We only exist because other animals don’t. Soon there will be something else standing above us, and the ruins of our world might then seem as strange as Quarxs does in 2022. “Remember Man, as you pass by, as you are now, so once was I. As I am now, so you soon will be, together in Eternity.”

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.