Living dolls are an ancient fascination. They are storied in every place that has stories, and sung about wherever there are songs. Pygmalion’s ivory bride; Hephaestus’s automata; Hidari Jingorō’s statues; the golems of Prague; Pinocchio; Sir Cliff…we seem fascinated by the idea of soul-sculpting, of lacing gears together so finely that sparks glimmer at the isthmus of the teeth.

Maybe the creation of life—actual life—is the ultimate goal of art. Mona Lisa’s smile is fake. Stare at it, and soon all you see is that it’s odd and uncanny. Leonardo da Vinci was a master, but in the end, he was stuck imitating life, and the reflection of the moon on the water will never be the moon. His Mona Lisa smiles because she has to. Imagine a painting that smiles because it wants to. No artist has succeeded at making a piece of artwork that actually lives. Unless God is an artist: according to Genesis, he formed us out of dust from the ground, so in a way, we’re his dolls.

But is it possible for a toy to live, while still remaining a toy? The point of toys is that they’re not alive: they’re a blank slate you fill with your personality and desire. Researchers at the Kibale National Park have observed adolescent chimps using sticks as toys, but the males use them as weapons or tools, while female chimps cradle them like babies. Toys are just shadows and reflections of their owners. The idea of a living, talking, thinking toy, with a will of its own, is a weird one. Maybe a horrible one.

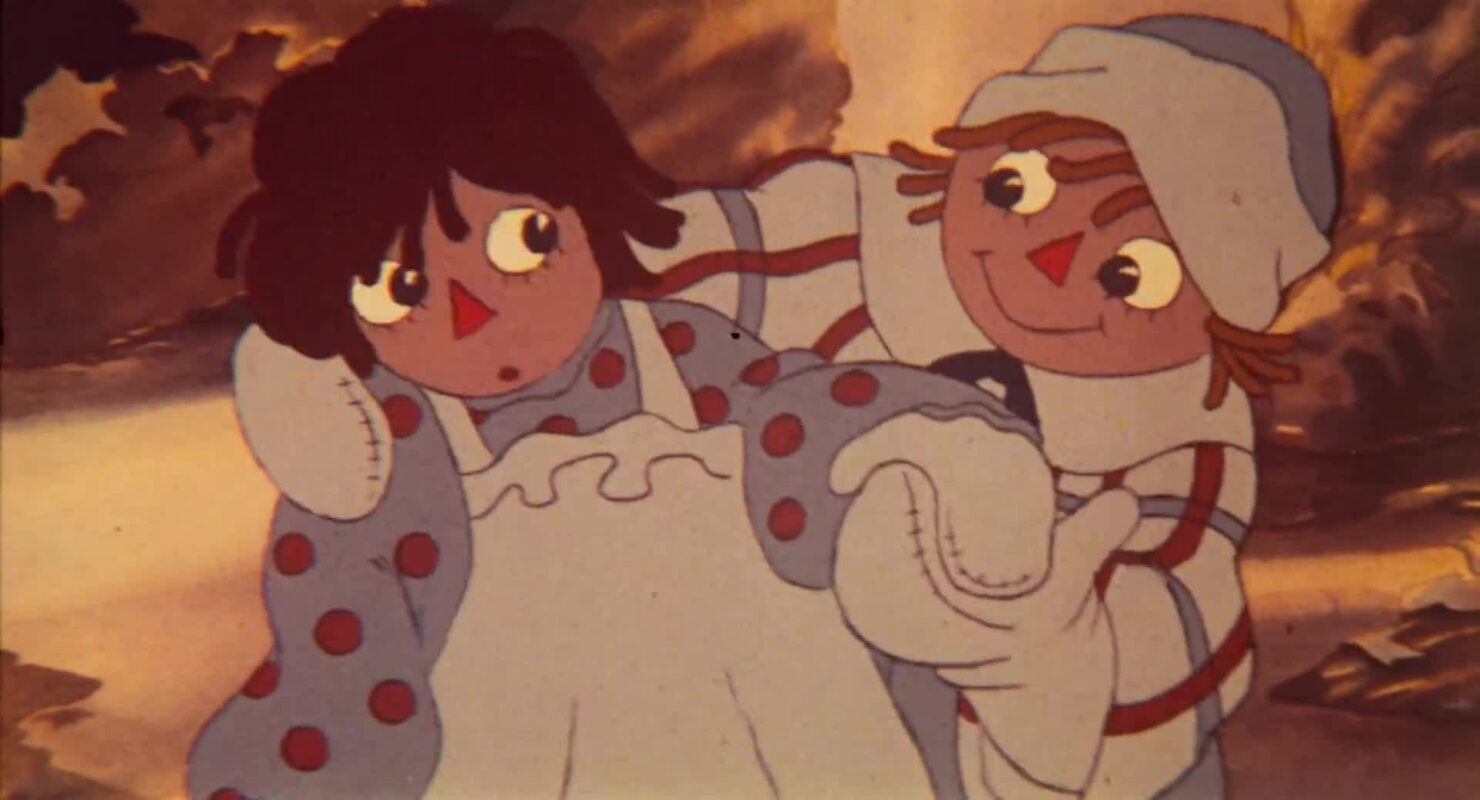

Richard Williams’ Raggedy Anne and Andy: A Musical Adventure is an animated film from 1977. Toys are preparing for their owner Marcella’s seventh birthday when a pirate captain breaks out of a snowglobe and kidnaps Marcella’s birthday present, a bisque doll named Babette. A loyal Raggedy Anne doll goes on an adventure to save her.

The film was a box office bomb, and ended up as airtime filler on CBS and the Disney Channel. It has a thin plot, and relies on beautiful animation and Joe Raposo’s music to carry it. Like all movies about living toys, it has existential implications. The toys in the movie conspire to make the life of children wonderful—that’s basically all that motivates them. Are they slaves? Do they have free will? Do they have the ability to judge? To hate?

The toys in Raggedy Anne and Andy exhibit Nietzsche’s slave morality. They are fully subservient to Marcella, not because she’s nice or worthy, but because of what they are and who she is. But they seem to possess awareness and introspection. Raggedy Andy is ashamed that he’s owned by a girl. The Twin Pennies are curious about what life is like outside the playroom. Most disturbingly, Raggedy Anne feels pain and discomfort at Marcella’s rough playing—the first thing she does is complain that she’s popped half her stitches. However, they seem to be at peace with their place in the universe. They can’t imagine freedom. The only characters who rebel are Babette and Captain Contagious, the villains.

The movie is charming, and lavishly animated by 1970s standards (until the production ran out of money—believe me, you’ll notice when this happens.) Of special note are Tissa David’s sensitive Raggedy Anne, Art Babbitt’s Grecian-tragic Camel With Wrinkly Knees (with each of his humps embodying a different personality), Emery Watkins’ voracious sucrose ocean Greedy, and the typical brilliance displayed in Richard Williams’ “No Girl’s Toy” sequence.

But it’s shamelessly schmaltzy, and feels decades older than 1977. I’d always assumed Raggedy Anne dolls were based off Anne of Green Gables (red hair + freckles), but this is not true. This is a movie based on a doll patented in 1915, and then a children’s book written in 1918, and you really feel those years. Raposo’s music is straight out of Tin Pan Alley.

The film was (possibly) funded by the CIA. It was distributed by the ITT Corporation, a shady manufacturing conglomerate with ties to the US executive branch: their involvement in Augusto Pinochet’s coup is now well-established. This was around the time the CIA was waging a so-called Cultural Cold War, which involved promoting “American” forms of art such as Broadway musicals. The source of funding was apparently an open secret among the film’s production team. Here’s a second or third hand story shared by Steve Stanchfield (by way of Garrett Gilchrist):

(Not speculation at all). Talked with Dick [Williams]. A friend had visited him and talked about how the CIA had funded the film. When I was talking with Dick about Emery [Hawkins] being fired, I asked if that was the CIA. Dick’s hands went in the air and he said loudly “those were the guys!!” and started to tell a story. His wife quickly came over and said “we’re not going to talk about that right now”. Later, while I was at the national archives searching for Private Snafu materials, I made a request to see material related to the CIA, ITT and Raggedy Ann and Andy. The freedom of information act is a wonderful thing. ITT was in trouble in GB and the states for being a front for the CIA. This led to the assassination of a candidate in South America, leaving egg on the face of ITT. They produced some childen’s programing to show they are a solid company with family values (and, of course, that idea is as ham-handed as it sounds). The programs were the Big Blue Marble and the animated feature Raggedy Ann and Andy. Raggedy Ann was to be released, at the latest, in the summer of 1976, in time for the big celebrations for the Bi-Centennial of the US. ITT bought Bobbs-Merrill for this purpose. Once the film was finished, they sold the Raggedy Ann film for $10 to Bobbs-Merrill and, somehow, allowed their assets to be sold back to itself. It is now owned by Random House. This is public record, and there’s many, many pages (thousands). I’ve just seen a handful.

If the ITT Corporation was indeed a spinnerette for taxpayer money, this could imply that part of the film belongs to the US public—ie, it’s public domain. As a pundit joked when obscenity charges were brought against a Robert Mapplethorpe photo of a flaccid penis, it probably won’t stand up in court, but I definitely feel less guilty than usual about giving this film the Captain Contagious treatment, if you know what I mean.

I’ve watched it once, and may watch it again. I maybe I won’t. Raggedy Anne and Andy is pleasant, but it’s not an unsung masterpiece.

The pacing is terrible. The film larded down by musical numbers—we get SEVEN songs before the first vestiges of plot emerge. It’s a “Musical Adventure” with MUSICAL in all caps and (adventure) in tiny-sized font. The small story is episodic. Raggedy Anne and Andy make a new friend, get into trouble, escape somehow, then repeat. Again and again.

But the movie’s flaws—the leisurely pace and incidental storytelling—do capture what it’s like to be a child, cooped up indoors on a rainy day, playing with your toys and making up adventures for them in your head. Or rather, what it once was like to be a child.

What would a kid born in a year starting with “201” think of this film? Would it provoke wonder? Or would it simply seem as an alien relic, undecodable and indecipherable? When I see children today, I am struck by how few of them still play with toys. Instead of Raggedy Anne, their hands are wrapped around a glowing shard of magic glass. It sings to them, enchants them, dreams for them, hurtles them algorithmically into an adulthood they’re not prepared for. Young girls are memorizing rules on how to diet and dress and say correct words and have correct thoughts. Their brothers watch aspirational lifestyle videos by a bald sex predator. The past depicted seems strange, but that’s not true: the world of 1977 is set in stone, remaining the same forever. We’re the ones who are strange. If there’s any character that represents today’s society, it’s the Greedy.

This movie will look like footage of a remote jungle tribe someday. Maybe that day has come already. It depicts a world and lifestyle foreign to us, a past that has come unraveled like Raggedy Anne’s stitches. For this reason alone, it’s worth watching—or at least, knowing about.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.