A cloud of iridescent energy slides across the galaxy, destroying all in its path. As it approaches Earth, James Tiberius Kirk bullies Starfleet into giving him control of the Enterprise, one last time. Incidentally, did James go through boot camp? Hard to imagine a guy called Tiberius doing push-ups and getting yelled at by R Lee Ermey. When your name is Tiberius they probably promote you straight to captain.

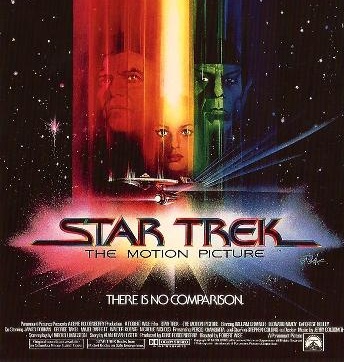

Star Trek: The Motion Picture is great, if in a troubled way. It’s like a titan, ready to collapse under its own weight. The philosophical method of”structuralism” seeks to understand things through their relationship to other things (eg, a ship’s mast can only exist if there are sails and a hull, otherwise it’s just a wooden pole), and Star Trek: The Bowel Motion Picture can only be understood in light of its own difficult creation.

Let’s start at the beginning. Once, there was a television show called Star Trek. It was both unpopular and cancelled. Half a century later, it’s the defining science fiction series of the silver screen.

How did this reappraisal happen? The same way the Velvet Underground became popular: they sold a few thousand copies, and all of those people started a band. Star Trek’s audience was tiny, but it consisted was of scientists, writers, activists, and other people who wielded a disproportionate impact on the tastes of 1970s America. Their beloved show was dumpstered, but these people were too aggressive to let it be forgotten. They rang phones. They wrote letters. The megaphone-wielding minority soon had the show firmly established in syndication, and a slow critical reassessment began: this thing is actually really good.

Star Trek was often campy, but never cynical or insulting. The writing was often broad, but was never boring. Gene Roddenberry was brilliant at directing attention away from the show’s weaknesses (its budget) and toward its strengths (screenwriting, and Shatner, Nimoy, and Kelley’s acting).

With voltage gathering for a continuation for the series, Paramount Pictures and Roddenberry began working on a pilot. It was a mess. Writers were commissioned, and their scripts rejected. Actors were hired, and their parts written out. Sets were built, then stripped down. I’m stunned that Burbank’s air was declared safe to breathe after so much burnt cash.

Finally, just weeks before shooting was due to start, Close Encounters of the Third Kind hit the box office like a wrecking ball. The prevailing cultural winds now favored movies instead of TV. Paramount panicked and changed their plans: when Star Trek returned, it wouldn’t be as a TV series but a motion picture.

This spelled disaster for Roddenberry. There was not enough time. The production was thrown into chaos, and the planned pilot was hastily refitted into a two hour movie, with a script written as they went along.

The result is a odd experience, stretched and deformed. It’s a Star Trek television episode viewed through a funhouse mirror: you can recognise the shape, but it’s 50% wider than it needs to be. The opening sequence is thrilling: three Klingon ships are evaporated in an impressive visual effects sequence. Exciting. Star Trek was back, now with a budget!

But then we get an hour of “character development”, meaning James T Kirk butts heads against the Enterprise’s dull new captain, while the plot spins its wheels and goes nowhere. We also meet a female alien called Ilya, who talks and talks and talks and sets records for uninspired character design. I’ll buy that a man with pointy ears might be an alien. Ilya’s literally just a woman with a shaven head. You can find plenty of aliens like her at the local slam poetry meet.

The film’s strengths are its visuals: something that was never a strong point with the original show. Douglas Trumbull and a young John Dykstra slather the frame with luminous rainbow hues (Trumbull previously worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the film owes a lot visually to that one, including a “smash cut from rainbow fluorescence to stark white” moment that matches 2001’s Star Gate sequence). The more practical effects are beefed up as well. A tiny Burbank sound stage is make to look like an absolutely massive cargo bay thanks to forced perspective (those tiny figures in the background? Children.) I think this is the first time we’ve seen a Star Trek space battle where both ships are composited into the same frame (as opposed to a shot/reverse shot of the Enterprise firing and another ship blowing up.)

The story is a bit perfunctory, and the imagery seems to transcend the characters until they’re reduced to spectators, gaping at the wonders of the cosmos. Maybe that’s the attitude Star Trek always tried to evoke. More likely, it’s a disguise for the fact that this was supposed to be a TV pilot, and they just plain didn’t have enough story.

I once saw a film called American Movie, about a pair of young indie filmmakers. One of them has a memorable monologue: “There’s no excuses, Paul. No one has ever, ever paid admission to see an excuse. No one has ever faced a black screen that says: ‘Well, if we had these set of circumstances, we would’ve shot this scene… so please forgive us and use your imagination.’ I’ve been to the movies hundreds of times. That’s never occurred.”

He should have seen Star Trek: TMP. It has excuses. Many of the visual effects (although stunning) don’t serve a purpose beyond “we don’t have any actual story to put here, enjoy these flashing abstract colors”. Big chunks of the film are a laser light show in space, intercut with shots of the crew looking awed. For a while, you share their awe. But then it feels like it’s time for something to happen.

Calling a movie “The Motion Picture” sounds either presumptuous of horribly underconfident: you’re either suggesting that it will be the definitive one, or the only one. In the case of ST:TMP, I can’t even call it A Motion Picture, as it’s been recut and re-released many times. The film is now legion, I’m not sure if the original version is exists today in a purchasable form. Although it’s a different sort of Star Trek, I enjoyed it a lot.

(It’s worth noting that Orson Welles voiced the cinematic trailers for this movie. One year later, he’d be voicing Manowar songs, and commercials for frozen peas.)

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.