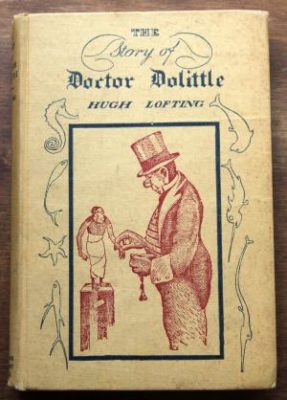

Action, adventure, and uncomfortable ethnic stereotypes; The Story of Dr Dolittle has everything you could ever want in an early 20th century children’s book.

The book (and the series that follows it) features a scatterbrained doctor with the ability to talk to animals. The first two or so Dolittle books follow a strict format: John Dolittle goes adventuring, gets into trouble, animals rescue him in a funny or interesting way, all of this happens again about ten or fifteen times, the end. Hugh Lofting soon grew in sophistication as a writer, the later books tend towards singular stories with allegorical themes. These often focus entirely on animals, dropping Dolittle out of the picture entirely.

There’s surprising philosophical acuity to Dr Dolittle. Wittgenstein said “If a lion could speak, we could not understand him”, and Hugh Lofting plays with this idea: humanity is cut off from the animal world by language, and this represents our failing. Who says animals don’t talk? Have you heard how incessantly birds chatter? How much dogs bark? Animals are always talking, constantly sharing thoughts and ideas, and we aren’t listening. The Dolittle books can be didactic on this subjects, and the latter ones feel written by a temporally displaced PETA activist. Often they verge on expressing outright contempt for humanity.

We have a good guess as to where Lofting’s antipathy comes from.

The Dr Dolittle tales started out as letters, scribbled and sent home from the trenches, and the author’s wartime experiences hang over the Dolittle tales like a flag’s shadow: never touching the story, but always present. The Great War was a bad one, industrial revolution alchemizing the battlefield, and a generation of young men witnessed entrails slithering out of bullet and bayonet wounds, faces melted by mustard gas, and mobile hospitals where the shrieking never stopped and the ground stank for weeks after. In the midst of this, Lofting was struck by the gallantry of horses and mules, and was embarrassed at how little his fellow men could do for them. He created John Dolittle in retribution, a physician who could give them the medical attention they seldom received in real life.

Other writers for children – JRR Tolkien, AA Milne, CS Lewis – also served in the war, and were influenced in various ways. Tolkien rejected modernity. Milne tried to wallpaper over reality with fantasy and whimsy (is it disturbing that he named his son “Christopher Robin”?). CS Lewis retreated into spiritual nihilism: nothing matters because the world shall soon dissolve like snow; the sun forbear to shine.

Lofting became a misanthrope. He believed, at the end, that humanity was a mistake, that we do not deserve our place on the planet. As the Dr Dolittle books progress, they get blacker and angrier, increasingly given to polemics about the irredeemable evil of humanity. I never finished Dr Dolittle and the Secret Lake, it was wearisome and depressing. Lofting’s disgust becomes a suffocating hand, strangling life from his stories. But that’s many decades away. The Story of Dr Dolittle is fun, with barely a hint of future despair.

As with most good children’s stories, it invites you to take it seriously and ask questions about its world. For example, when does the story take place? The opening passage says that it happened “when our grandfathers were little children”, and the parrot Polynesia (who claims to be either one hundred and eighty one or one hundred and eighty two years old) describes seeing King Charles II hiding behind an oak tree, an event that happened in 1651.

This dates the book to no later than 1832, and makes aspects of it anachronistic – John Dolittle wouldn’t be able to vaccinate the sick monkeys, for example. There’s clues that the book might be set even earlier – the doctor is menaced by Barbary pirates, who had been pacified for over fifteen years by that time. But that would throw still more story elements out of date: such as an Italian organ grinder with a monkey (which is an artifact from the 19th century). The monkey in question later tells stories passed down by his ancestors about “…lizards, as long as a train, that wandered over the mountains in those times, nibbling from the tree-tops.” This was interesting. People in 1920 knew about dinosaurs, but didn’t know they lived in a different time to primates.

Something should be said about the story’s…uh, racial complexities. In short, John Dolittle ends up at the mercy of an African tribe, whose prince, Bumpo, wishes to become a white man. In return for freedom, the ever-resourceful John Dolittle uses medicine to bleach the prince’s face.

Make of that what you want. My two krugerrand: Bumpo is a strange man and his desires are clearly depicted as abnormal in the story (one character calls it a “silly business”, and another states that he looked better as a black man). And given that skin-lightening is now an industry worth tens of billions of dollars (with over 70% of Nigerians using some sort of skin-lightening product, according to WHO), a desire for paler skin clearly isn’t an idea that sprung wholesale out of Hugh Lofting’s evil, racist brain.

The book’s imaginative, but sometimes I wish it went a little further. The episodic “adventure / problem / escape” format can get repetitive, and there’s fascinating possibilities left unexplored. Long chunks of the book involve the doctor trying to bring a rare beast back from Africa – a “pushmi-pullyu”, which has a head at each end of its body (there’s an argument that Dr Dolittle inspired Nickelodeon’s Catdog). The Doctor plans on exhibiting the animal as a sideshow, thus saving himself from financial ruin. One wants to yell at him “You can talk to animals! There are thousands and thousands of ways you could become rich! Use mice to steal the crown jewels! Use paper wasps make casts of the locks to the Bank of England! Use dolphins to patrol the sea floor and find sunken treasure!” If the Doctor wanted to, he’d be running the British Commonwealth within twenty years.

But those goals would be amoral. John Dolittle is so saintly he’s boring, and I wish he had a Moriarty: someone who shares his zoolinguistic powers but uses them for evil, not good.

The Dr Dolittle series enjoyed a good run, but it doesn’t seem to be remembered alongside Winnie the Pooh and Alice in Wonderland. Do the racial elements make the books unsalvagable? That would be a shame. In 1998 it was loosely adapted as big budget Hollywood comedy starring Eddie Murphy, and again as an accidental comedy starring Robert Downey Jr. No doubt it’s being reprinted inside plague bags lest innocent bystanders be infected with racism or something. Buy it however you can find it.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.