In the 80s, we thought we’d be bombarded by nuclear missiles. Instead, we were bombarded by films about nuclear missiles. The United States initiated this conflict in 1983, with WarGames and The Day After. The USSR retaliated in 1986 with Letters of a Dead Man. The United Kingdom wasn’t slow to unleash its own nuclear missile film arsenal, with Threads exiting the bomb bay doors in 1984 and the animated When the Wind Blows following in 1986. Fortunately, the average film has a very small radioactive footprint, or none of us would have survived.

In the 80s, we thought we’d be bombarded by nuclear missiles. Instead, we were bombarded by films about nuclear missiles. The United States initiated this conflict in 1983, with WarGames and The Day After. The USSR retaliated in 1986 with Letters of a Dead Man. The United Kingdom wasn’t slow to unleash its own nuclear missile film arsenal, with Threads exiting the bomb bay doors in 1984 and the animated When the Wind Blows following in 1986. Fortunately, the average film has a very small radioactive footprint, or none of us would have survived.

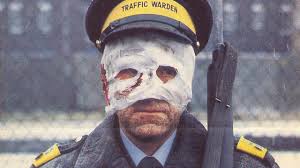

“Threads” is probably the most memorable of these films. It traumatized children upon its release, and even now it’s a compelling watch.

The film opens like a sitcom, with a couple in Sheffield decorating their flat. Television broadcasts warn of impeding nuclear war. Usually, sitcoms have to deal with their cast quitting the show, aging out of their role, or getting caught snorting coke. Threads solves the problem by killing almost the entire cast, and a great many people besides.

Soon, the cold war becomes extremely hot, and the world is engulfed by a three gigaton nuclear firestorm. Regrettably, some people actually survive. The rest of the film documents their struggles in the desolate aftermath. Society collapses to subsistence level. Basic wants are in dire need. We start to wonder about genetic mutations and birth defects, and the final scene gives you a lot to think about.

There are a lot of unforgettable images in Threads. A woman cradling a charcoal-black baby. Glass milkbottles instantly flash-melting. A burning cat. After nuclear winter collapses the biosphere, we see a door to door salesman selling dead rats for meat.

The film is almost comically grim, and you start to wonder if it’s supposed to be a parody of nuke films. If it is, it fooled me. I can’t find a single moment where the cast (or director Mick Jackson) winks at the camera – everyone handles the material with dour seriousness.

The BBC’s small budget works well for the film, giving it a filthy, lived-in quality. Sometimes the cheapness adds a new dimension to the horror, as in the hospital scene where open wounds are being sterilized with supermarket containers of Saxa salt.

There’s something intrinsically frightening about nuclear weapons. Perhaps it’s their hopelessness, and the way they knock the traditional rules of war into a cocked hat. Once, better weapons meant you were in a favorable position. Bill has a stick, and uses it to guard his food. Bob has a bigger stick, and uses it to take Bill’s food. So far, so good. But now Bill has a B53, and Bob has a RS-28, and now when they go to war neither of them will win. There will be no Bill, no Bob, and no food to fight over. They’re the most ghastly “off switch” ever achieved. And the only way to prevent their use is to…make more of them?

This is the sort of movie that dirties your TV screen or monitor. You think, your finger will come away coated in dirt and soot. It is a fantastic film that I don’t plan on seeing again, which I think was the goal.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.