In the 1970s, there was a book called The Anarchist Cookbook. Hippies had many gods and many bibles: this was the bible of the Church of the Broken Window.

In the 1970s, there was a book called The Anarchist Cookbook. Hippies had many gods and many bibles: this was the bible of the Church of the Broken Window.

It’s a “how to” guide for picking locks and phreaking phones and building shoebox bombs. Never outright banned in America, it was nevertheless printed in small quantities and was highly sought after in certain circles.

Unfortunately, many of the recipes were a little “off”, plus the people who tried them generally didn’t know what they were doing. The book’s actual recipe was 1) dumbass kids try to make nitroglycerine 2) they blow off their own fingers or burn down the Podunk High gym hall 3) juvie prison sentences all around, plus the school goes into lockdown from now until the end of time. There is quite possibly more authoritarianism in the world thanks to The Anarchist Cookbook than there would have been without it.

There were always conspiracy theories that the Cookbook was written by an “outsider” trying to discredit or sabotage the anarchy movement from within. As of 2013 the copyright resided with a publisher just two blocks away from a National Security Agency depot in Arkansas, but that’s probably a poetic concidence. Regardless of the author’s intentions, the book could be viewed as reverse-activism, advocating violence and accidentally making the world a safer and more secure place.

Or maybe the world would have become safer anyway – books usually don’t matter much. Writers are very excited by the prospect of book burning, the way Christians are excited by tales of Satanic cults running global governments, and it’s easy to see why. Life frequently stomps on us, seemingly for no reason at all, and it’s flattering to believe that we’re being stomped on because we’re important.

BBSs soon became popular, and the Cookbook obtained a fragmentary second life. Bits of it (literally) were streamed over 1200 baud modems, often interpolated with additions by someone calling himself “The Jolly Roger”. This person appeared to be barely literate, someone who learned English from the txt files in Doom wads, and his advice was even worse than the original’s.

“Break a ton of matchheads off. Then cut a SMALL hole in the tennis ball. Stuff all of the matchheads into the ball, until you can’t fit any more in. Then tape over it with duct tape. Make sure it is real nice and tight! Then, when you see a geek walking down the street, give it a good throw. He will have a blast!!” -Jolly Roger-

Consider putting a fuse in the tennis ball too, otherwise it won’t blow up and he’ll think you’re challenging him to tennis for two. Aerobic exercise is linked to positive health outcomes, and you won’t have killed him, you’ll have made him stronger.

Decades later, the author of The Anarchist Cookbook went public and disowned the book (thus inspiring even more people to seek it out and learn its recipes). This page has now been viewed by hundreds of thousands of eyeballs. Do you doubt that at least one pair belong to a young, impressionable person who will actually try the recipes in the book? And that we’ll soon hear about him on the news, along with the twenty or thirty unfortunates who happened to be standing near his trailer at the time?

I don’t believe William Powell has ever made a decision that worked out the way he wanted it to. He should have gone to Vietnam and watched the war effort crumble within a week. Or advocated for cleaner streets and watched as whole communities drowned in an apocalyptic tide of cigarette butts and plastic bags. There are hippie gods, and hippie bibles. William Powell was the hippie Jonah.

No Comments »

Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will soon collapses inwards under its own largeness and lack of substance. Scene after scene of columns of soldiers marching, or standing in massed formation on parade grounds. The viewer gets bored, and starts trying to see signs of humanity intruding on the edge of the celluloid.

Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will soon collapses inwards under its own largeness and lack of substance. Scene after scene of columns of soldiers marching, or standing in massed formation on parade grounds. The viewer gets bored, and starts trying to see signs of humanity intruding on the edge of the celluloid.

Wow, that sure is a lot of soldiers. Are some of them uncomfortable? Do they have itches they aren’t allowed to scratch? Where are they billeted and fed? Were there latrine pits dug somewhere? Where did Hitler go to the toilet? I would have liked a film made about these topics, and in a way, Riefenstahl made a film about the most boring aspect of Hitler’s rise to power.

I feel this way about many films: where the camera all but twists and cavorts to avoid capturing things that might be exciting. For example, although I don’t like the James Bond films, many things in their background are absolutely fascinating.

For example, the man called Ross Heilman.

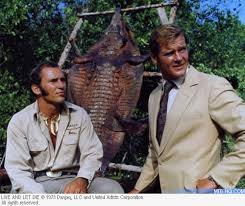

He was a Jew from Florida who moved to Jamaica, renamed himself “Ross Kananga”, claimed Seminole heritage, and opened a crocodile farm. Some people have biographies that seem to be written by a random word generator, and he was one of them. At the height of his success Ross had more than a thousand crocodiles, and he would harvest their skins. In those days, crocodile skin sold for $2 a pound, and $450 for a reasonably good entire skin.

One day, location scouts for the film Live and Let Die discovered the farm, and wanted to use it as the fictional nation of San Monique. Ross obviously made quite an impression on the cast and crew, because they named the villain of the film “Kananga”. Ross doubled for Roger Moore in the infamous scene where he jumps across a river on the backs of living crocodiles, something that was hazardous to his health.

Something like that is almost impossible to do. So, I had to do it six times before I got it right. I fell five times. The film company kept sending to London for more clothes. The crocs were chewing off everything when I hit the water, including shoes. I received 193 stitches on my leg and face.”

Ross never became a film star, and he did not have long to live. In 1978, he died of cardiac arrest while spearfishing in the Everglades. Or so some stories say. There is a conspiracy.

This is from the autobiography of inventor, businessman, and filmmaker Arthur Jones.

“Later, he had so many people after him that he decided the only way out was to fake his own death, so that people would stop looking for him; so he took his grandmother out in a small boat in the Everglades in order to have a witness to his death. The plan being to turn over the boat in a spot where she could easily escape, but where he could get away; leaving the impression that he had drowned, even though his body was never supposed to be found.

“But it was found; it was a cold day, and he went into shock and did drown. The grandmother did get out alive, and was able to provide a true account of his death.

“I was after him for having done one of the cruelest things I ever witnessed; he tied a bunch of crocodiles very tightly, packed them in a big trailer and then left them there for weeks. When their legs were untied their feet were already rotting off, even though they were still alive. I figured tit for tat, nit for shit, and had similar plans for him; but he was dead before I could find him. Several other people had plans for him as a result of some of his other stunts.”

It sounds implausible and hard to believe (and might have pleased Ross Heilman in this regard), but I wonder if it’s common for a man to suffer cardiac arrest at the age of 32.

No Comments »

“One” by Metallica has a famous section at 4:32 where Lars Ulrich plays a syncopated sextuplets on the kick drums (6 beats on, 2 beats off)…and then James Hetfield doubles it on guitar. The effect is dramatic: the guitar sounds like a machine gun.

“One” by Metallica has a famous section at 4:32 where Lars Ulrich plays a syncopated sextuplets on the kick drums (6 beats on, 2 beats off)…and then James Hetfield doubles it on guitar. The effect is dramatic: the guitar sounds like a machine gun.

The effect wouldn’t have worked if he’d played the cello. There’s something natural about the pairing of electric guitars and automatic guns. Although not a full rhyme, they’re at least a slant rhyme for each other. The force. The percussion. The volume. The way they harness bolts, pins, voltage, and steel to amplify something in the human condition.

But there are many guns, and if you’re drawing a comparison with high-gain metal, there’s only one gun that fits the bill. The most famous gun.

In 22 June 1941, the Wehrmacht tide overflowed Russia’s borders. Millions of Russians were killed, and millions more were wounded. In the latter category was a mechanically-inclined man called Mikhail Kalashnikov, who spent his convalescence studying mechanics and firearm design. After a few false starts and setbacks, he created his masterpiece: a gas-powered imitation of German assault rifles called the Avtomat Kalashnikova 1947 – more famously known as the AK-47.

In doing so, he joined the ranks of men like Samuel Colt, Hiriam Maxim, John Browning, and Richard Gatling – men with names that have become death. The classical Greeks believed that a society grows great when old men plant trees. Kalashnikov and his ilk are the second sort: the ones who provide fertilizer for the trees. I wonder if Mr Kalashnikov ever stayed awake at night, thinking of the bodies. All the millions and millions of them.

The AK-47 is a pragmatic weapon, easy to use, even easier to die from. Despite being ergonomically uncomfortable (and not particularly accurate), they’re cheap, can be mass produced, and function even when clogged with dust, mud, blood, sweat, and unburnt propellant. At one point, they killed 250,000 people per year. They adorn the Mozambique flag. They are simple enough for a child to use. Children often have.

Functionally, they are similar to the WW2-era German MP42 Sturmgewehr (lit: “Storm-Rifle”). I haven’t found any sources to indicate that Kalashnikov was wounded by an MP42, but it would be funny if he had. In any case, the Germans lost. The world was changing, and superior rifles no longer won wars. Truthfully, by the time Kalashnikov arrived on the scene, they didn’t even win battles.

But the world no longer has battles. Now, almost all fighting is irregular, conducted by some flavour of guerilla forces. Afghanistan. Vietnam. Sudan. The Clauswitzian ideals of battle are over, and now being a soldier means you’re crouched in a jungle, motionless, made of matter almost indifferentiate from the the mud and leaves on the ground, so fascinated by what’s beyond your gunsight that you don’t even move when a mosquito lands on your lip. In this new era of undeclared wars and uniformless fighters, the AK-47 thrives. It’s the embodiment of a Communist weapon, a different, louder voice for the proletariat.

But what about guitars? What’s the connection?

Once, music was entertainment for the rich – formal, stultified, encased in tradition. A symphony orchestra contains four rigid groups of musicians – woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings – with other subdivisions within. Everyone has a role to play, and roles that they cannot. What was that Heinlein quote about specialisation being for insects? Symphonies have always sounded cold to me, and maybe that’s why. They remind me of a hive.

Guitars are very much a common person’s instrument. They’re easy to make, easy to learn, and versatile. You can play them standing up or sitting down (evocative of the marksman’s choice of firing from the hip or the shoulder), you can play them while singing, and you can play them any way you want. There are no rules with guitar. You can change from strumming chords to playing lead melodies on the higher frets. If the guitar has a hollow body, you can slap it with your palm for percussion.

You can play a guitar sloppily and still sound good. For some styles of music (eg, grunge and shoegaze), it’s almost mandatory that you play sloppily. If a guitar goes out of tune, you can retune them in the middle of a performance. And they can take massive amounts of abuse. Ask any rock musician just how hard it is to smash a guitar on stage.

But guitars are quiet, and need amplification. The Beatles famously quit touring because they couldn’t hear their instruments over the sounds of screaming fans. Through the sixties and seventies, the wattage of stage equipment kept rising, and soon artists could impose their visions at literally deafening volumes.

In short, the guitar is to instruments what the AK-47 is to guns: a multi-purpose tool. They’re a transition from a world where maps dictate territories (the limitations of classical instruments and classical weaponry were both defining factors in the character of early war and music), to a place where the tool is servant and slave to the master’s voice.

Is there some link between the mutating forms of music and guns? Does it reflect some deeper change in the currents of the world? Biologically, evolution can follow two routes: divergence (where a species splits into two dissimilar lifeforms), and convergence (where two dissimilar species evolve to look like each other). A good example of convergence is the thylacine, which looked and acted rather like a fox despite belonging to the marsupial class. The stripes give the game away, but the skeletons are so close that it takes an expert eye to separate them.

Small arms and musical instruments almost seem to be following convergent evolution: fast, efficient, interchangeable, and they even look similar. Roy Orbison starred in a terrible movie called Fastest Guitar Alive, about a man who has a gun inside a guitar case. Maybe that’s generic, and every guitar is halfway to a gun (or vice versa). Guitars are sometimes called “axes”. We should update our terminology.

(For an earlier example of machine gun drumming, listen to “Darkness Descends” by Dark Angel at 0:53.)

No Comments »

In the 1970s, there was a book called The Anarchist Cookbook. Hippies had many gods and many bibles: this was the bible of the Church of the Broken Window.

In the 1970s, there was a book called The Anarchist Cookbook. Hippies had many gods and many bibles: this was the bible of the Church of the Broken Window.