One of aviation’s great unsolved mysteries is the disappearance of BSAA Flight CS-59.

The plane – which had the call sign Star Dust – left Morón Airport at Buenos Aires, Argentina on Aug 2nd 1947, bound for Los Cerrillos Airport in Santiago, Chile.

Aboard was a cast worthy of an Agatha Christie novel: two businessmen; a Palestinian man rumored to have a diamond stitched into his jacket; a South American sales agent with connections to the Romanian throne; a seventy year old German émigré; and a British civil servant carrying a “diplomatic bag” bound for the UK embassy.[1]“The Star Dust Mystery.” Damn Interesting, 2 Aug. 2015, www.damninteresting.com/the-star-dust-mystery. The plane itself was a sturdy Avro 691 Lancastrian MkIII, capable of 310mph airspeeds and 20,000ft altitudes, piloted by decorated RAF veteran Reginald Cook.

The Star Dust entered Chilean airspace in the late afternoon, with radio operator Dennis Harmer maintaining contact with Los Cerrillos. Nothing unusual was reported. Then, at 5:41 p.m, Harmer transmitted the message “ETA SANTIAGO 17.45 HRS STENDEC”.

The Chilean air traffic controller didn’t understand the last word, which was neither ATC terminology nor a word in any language she recognized. She asked for clarification. Harmer tapped out “STENDEC” twice more.

This was the last transmission ever received from the Star Dust. It did not arrive at Los Cerrillos, and a five-day search uncovered no trace of the missing plane.

The Star Dust‘s disappearance remained a total mystery for fifty years. Theories included aliens, a trans-dimensional rift, aliens, foreign hijacking, and aliens. It became part of “vanished plane” lore along with the Bermuda Triangle—a triangle that seemingly has sixteen points and extends across 80% of the Atlantic Ocean—and (much later) Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.

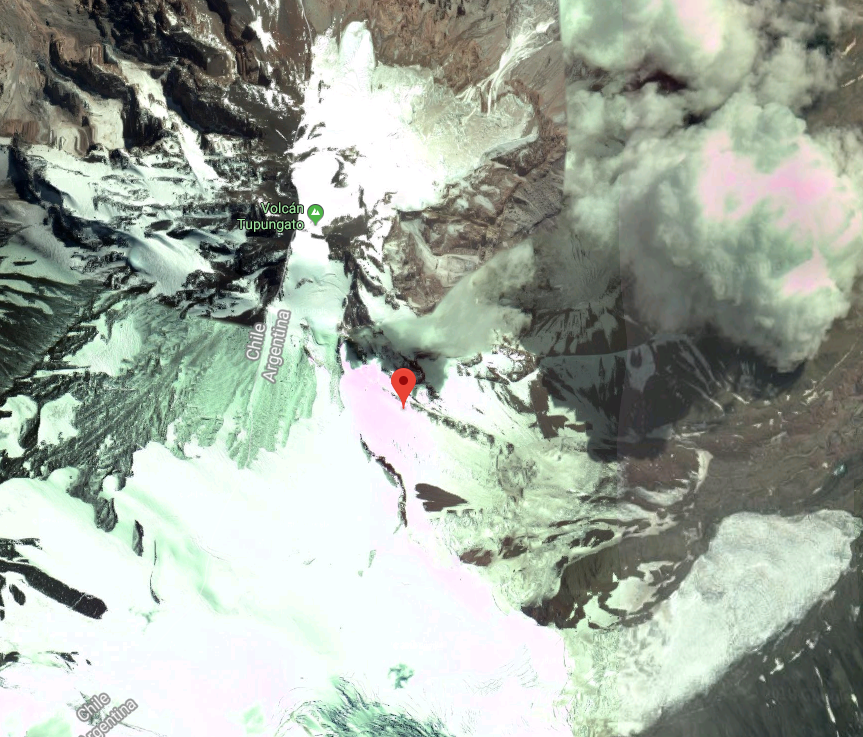

In 1998, mountaineers climbing Mount Tupungato’s southwest face found wreckage 15,000 feet above sea level. Pieces of metal. Shreds of clothing. A corroded Rolls Royce engine, jutting from the ice. The Star Dust had never come down from the sky. Subsequent expeditions by the Chilean army and air force uncovered more of the wrecked plane.

The wreckage was scattered across a narrow area, ruling out a mid-air explosion. The Star Dust’s propellers was twisted and bent back, suggesting the engine had been running at the moment of impact. A fully inflated tire indicated that the plane hadn’t deployed its landing gear.

We can guess how the plane crashed: it was caught inside the jet stream (a poorly-understood phenomenon in 1947) which exerted backward drag on the plane, causing it to cross less distance than expected.

Imagine running while blindfolded. In theory, you could calculate the distance you have travelled by counting your steps (assuming your stride is of fixed length), but if you accidentally step onto a moving treadmill, your calculations will end up wrong. You’ll think you’re moving forward when you’re actually standing still.

The Star Dust hit the jet stream, which acted like a treadmill, slowing it down. This wouldn’t have caused a problem…if the pilot had known it was happening. Inside the cockpit—surrounded by shrieking white, guided by primitive WWII-era navigational instruments—Reginald Cook greatly overestimated the distance he’d crossed. He’d thought the plane was directly over Santiago, when it was actually still fifty miles east. He also thought they’d safely crossed the Andes range, when they were plunging into its face.

The technical term for the crash is “controlled descent into terrain”[2]Pilot, By Plane And, et al. “A Pilot’s Last Words: ‘STENDEC.’” Plane & Pilot Magazine, 12 Dec. 2019, www.planeandpilotmag.com/article/a-pilots-last-words-stendec. – a fancy way of saying Cook flew the plane into the mountain. The impact buried the Star Dust in ice, but recent melt-off at Tupungato exposed the engine. There are fascinating rumors that local arrieros (high-altitude mule-handlers, the Andean equivalent of the sherpas) knew of the Star Dust crash long before 2000. [3]Maynard, Matt. “Searching for Star Dust: The Hunt to Uncover an Andean Mystery – Geographical Magazine.” Geographical, 2019, … Continue reading

Tupungato’s southwest face is deadly even when you’re not crashing into it at 310mph. Making the ascent requires skill and daring: only four independent mountaineers have reached the crash site, two of whom died in the process.[4]Ibid. In recent years Argentinian policy has forbidden mountaineers from even attempting to reach the crash site. The plane’s discovery was a red-letter day for Argentina—finally, Anglo-Argentinian history that didn’t involve bombed islands or offside football goals—and they would prefer that the Star Dust doesn’t claim any more lives. Search teams have located many fragments of the Star Dust (including a severed hand from the stewardess, her fingernails still painted[5]Maynard, Matt. “Searching for Star Dust: An Epic Quest to Find a near-Mythical Plane Wreck.” Red Bull, 19 Nov. 2019, www.redbull.com/au-en/star-dust-mystery-1947-plane-wreck-quest.), and will surely find more.

But the meaning of Dennis Harmer’s final “STENDEC” transmission has never been explained. There are many competing theories, none of them fitting all the facts.

1. “STENDEC” is an anagram for “DESCENT”.

If Harmer had meant to write “DESCENT”, he obviously would have done so. RAF radio operators are trained to signal clearly, not in word games and riddles.

2. Harmer was suffering from altitude sickness or hypoxia, and mixed up his message.

While this might seem plausible, it’s not easy to accidentally switch letters in Morse (signaling C alone requires four distinct pulses in a precise order) the same way it is on a keyboard. In any case, Harmer repeated the word multiple times; clearly he meant to write it.

3. “STENDEC” shares many letters with “Stardust”.

Planes in the air are identified by registration code (G-AGWH in the Star Dust’s case), not the fanciful names bestowed by the airlines. Also, why would an operator sign off by telling Chilean air traffic control the name of his plane (which they already knew)?

4. “STENDEC” is obscure RAF shorthand for “Severe Turbulence Encountered, Now Descending, Emergency Crash-landing”[6]“NOVA Online | Vanished! | Theories (Feb. 8, 2001).” PBS, 2001, www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/vanished/sten_010208.html..

This doesn’t fit the first half of the message. Harmer had just said that the Star Dust would shortly be arriving in Santiago.

5. “STENDEC” is spy code.

What sort of spy code? What was a random Chilean air traffic controller supposed to do with it? How did Harmer (or whoever wrote the code) expect it to reach the right set of ears?

5a “STENDEC” stands for “Saturday, 10th of December”.

Sounds good, except that December was a Wednesday that year.

6. It’s possible (but again, uncertain) that the word was mistakenly deciphered by radio control, due to limitations of the Morse code cipher.

Translation is easiest when two languages share all the same features, and harder when Language 1 possesses some property that isn’t present in Language 2, or vice versa. Early Biblical manuscripts were written in scriptio continua, in an unbroken flow of unmarked text.

This creates textual ambiguity, with sentences that change meaning depending on where a translator or copyist chooses to insert spaces and punctuation. For example, the Greek Septuagint of Romans 16:7 runs A S P A S A S T H E A N D R O N I K O N K A I I O U N I A N T O U S S U G G E N E I S M O U K A I S U N A I K H M A L O T O U S M O U O I T I N E S E I S I N E P I S E M O I E N T O I S A P O S T O L O I S O I K A I P R O E M O U G E G O N A S I N E N K H R I S T O, which the King James Version translates as “Salute Andronicus and Junia, my kinsmen, and my fellow prisoners, who are of note among the apostles, who also were in Christ before me.” The problem is that the accusative noun IOUNIAN can have one of two accent marks (IOUNÍAN/IOUNIÂN), which would make it either a man’s name or a woman’s. We still don’t know the gender of this “Junia”.[7]Omanson, Roger L. 1946-. “Punctuation in the New Testament. If Only Paul Had Used the Chicago Manual of Style.” Bible Review , vol. 14.6, 1998, pp. 40-43.

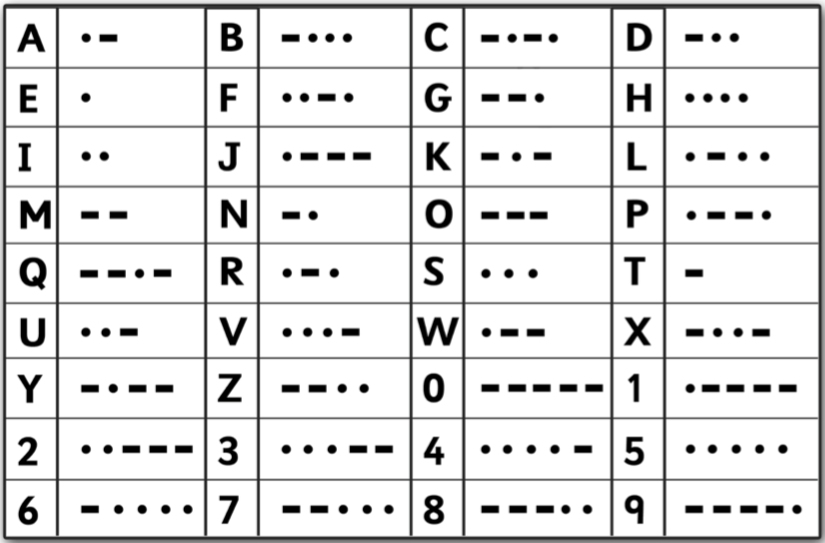

Morse isn’t a foreign language (it’s a cipher for English), but it’s scriptio continua. Its dots and dashes represent 26 letters and 10 numbers, but there’s no special character for a space. Operator convention[8]“Morse Code & Abbreviations.” Portland State University, 2021, web.cecs.pdx.edu/%7Ecaleb/aa7ou/ham_pages/morse_abb.html. is that spaces between letters are signaled by a pause equal to three dots, while spaces between words are signaled by a pause equal to seven dots. But if the signaler is in a hurry (or panicking), the pauses might get shortened, creating an ambiguous message that could be read multiple ways.

The exact transmission was.

… – . -. -.. . -.-.

The Chilean air traffic controller spaced it like this: STENDEC.

… / – / . / -. / -.. / . / -.-.

But it could also be spaced like this: STAREAR

… / – / .– / .–. / . / .–.–.

A typical “end of message” signoff at the time was “AR” (with no spaces.)[9]“An Explanation of STENDEC …..” Fly with the Stars, 2021, www.flywiththestars.co.uk/Documents/STENDEC.htm., and it’s possible that the sequence could have meant “STandard ARrival from East + signoff.”

This (along with other ways of re-ordering the message) raises as many questions as it answers. How did the Chilean air traffic controller misread this supposedly commonplace message so badly? And how did she repeat the same mistake two more times? And why didn’t Harmer clarify or rephrase?

All explanations suffer from one of three basic weaknesses:

1) Harmer signalled “STENDEC” multiple times. This completely rules out a mistake, and makes it far less likely that the Chilean air traffic controller misunderstood the spaces. (“Tell ’em three times” is a simple but reliable error-correcting trick in communications theory). 2) Harmer had no reason to write in code. If the Star Dust had been about to crash, he would have said so. If its navigational instruments had failed, he would have said so. Explanations that rely on “deciphering” Harmer’s final transmission like a puzzle provoke the question of why this would even be necessary. 3) There’s no hint that anything was amiss. The retracted landing gear, the running propeller, the casual tone of the message…there’s zero sign that anyone aboard the Star Dust knew they were in trouble until they died against the side of Mount Tupungato.

The Andean glaciers are still melting. It’s possible we’ll recover more wreckage from the Star Dust, but will we ever know what STENDEC means?

[Update] The mystery is solved. “STENDEC” stands for “Stop Trying to ENcode and DEcode this Conundrum.” Glad we could put that one to bed.

References

| ↑1 | “The Star Dust Mystery.” Damn Interesting, 2 Aug. 2015, www.damninteresting.com/the-star-dust-mystery. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pilot, By Plane And, et al. “A Pilot’s Last Words: ‘STENDEC.’” Plane & Pilot Magazine, 12 Dec. 2019, www.planeandpilotmag.com/article/a-pilots-last-words-stendec. |

| ↑3 | Maynard, Matt. “Searching for Star Dust: The Hunt to Uncover an Andean Mystery – Geographical Magazine.” Geographical, 2019, geographical.co.uk/people/explorers/item/3213-searching-for-stardust. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Maynard, Matt. “Searching for Star Dust: An Epic Quest to Find a near-Mythical Plane Wreck.” Red Bull, 19 Nov. 2019, www.redbull.com/au-en/star-dust-mystery-1947-plane-wreck-quest. |

| ↑6 | “NOVA Online | Vanished! | Theories (Feb. 8, 2001).” PBS, 2001, www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/vanished/sten_010208.html. |

| ↑7 | Omanson, Roger L. 1946-. “Punctuation in the New Testament. If Only Paul Had Used the Chicago Manual of Style.” Bible Review , vol. 14.6, 1998, pp. 40-43. |

| ↑8 | “Morse Code & Abbreviations.” Portland State University, 2021, web.cecs.pdx.edu/%7Ecaleb/aa7ou/ham_pages/morse_abb.html. |

| ↑9 | “An Explanation of STENDEC …..” Fly with the Stars, 2021, www.flywiththestars.co.uk/Documents/STENDEC.htm. |

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.