Aeon Flux S3E7, or “Chronophasia”, is one of the most confusing episodes ever put on TV for any series. You can literally feel your brain get further away from understanding it the more you subject yourself to it.

Tireless on your behalf, I have uncovered a few hard facts. For example, it’s the seventh episode of Aeon Flux’s third season, and I believe its title is “Chronophasia”.

How long does this go on? Always.

This episode triggers brain bleeds in fans.

Just have a glance at can anyone really explain chronophasia?, a twenty-five year old discussion where three Aeon Flux writers show up. And the result, after a quarter-century of argument?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Some have argued that “Chronophasia” has no meaning: that it’s either very badly written or a troll episode designed to enrage the kind of fan who obsesses over who killed Laura Palmer.

“So, in answer to the original poster, after all these years, with posts from people actually involved in the writing and creation of the short….No.

No, they can not tell you the meaning of it. No, they have not written an explanation of it. They don’t know why the baby was so powerful. They don’t know if the boy was there from the beginning. They don’t know what was in the vial at the end or why it aided in changing their reality. They have no idea why or how the mummified people died.

They have no idea what was created or why it was created(save to make a buck). It’s like watching a David Lynch film minus the few parts that make sense enough to string together a movie.

Absolutely nothing is to be gained on examination of this short other than that pieces have been placed in opposition and are blatantly left without any conclusion. It is not a reflection of life, metaphysics or science. It is a nothing. You can sleep easy now.

They divided by zero and the zero won.”

- ILXOR user iseewutudidthere

I don’t agree with this reading. “Chronophasia” is messy and unfocused, but there’s a dreamlike logic to it. And from a certain perspective, it does kind of make sense..

There’s just too much of it: the plot’s a 10-piece puzzle that has 11 or 12 pieces. There are a few different ways to assemble the puzzle so that it forms a complete picture, but there will always be pieces left over. We just have to be happy with that.

“There was never supposed to be one “right,” comprehensive interpretation of the episode (just as there is no “right” answer to whether or not there is an active virus or which — if any — of the scenarios represents “reality”). Ultimately dream logic prevails — tons of meaning but the solution never quite comes together in a consistent, comprehensive way. A number of possible dualistic alternatives are set up — waking vs. dreaming, madness vs. sanity, reality vs. illusion, virus vs. no virus, science experiment gone wrong vs. ancient evil, baby as victim vs. baby as killer, boy as good vs. boy as evil (also, boy as child vs. boy as man), Aeon knows more than Trevor vs. Trevor knows more than Aeon, and so on — and it’s never clear (to us or Aeon) where things really stand (for all we know this whole thing is Trevor’s elaborate mindfuck/practical joke at Aeon’s expense, with the boy and baby merely players or props). If there is any clear realization at all, it is merely that waking up repeatedly on a stone slab drenched in blood is ultimately not all that much more puzzling or bizarre than waking up repeatedly on a Sealey Posturpedic Mattress.”

The story

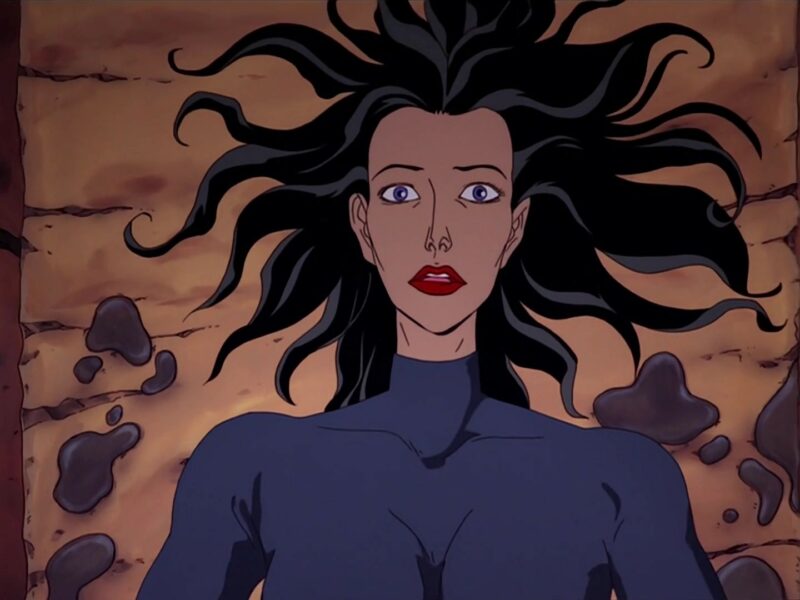

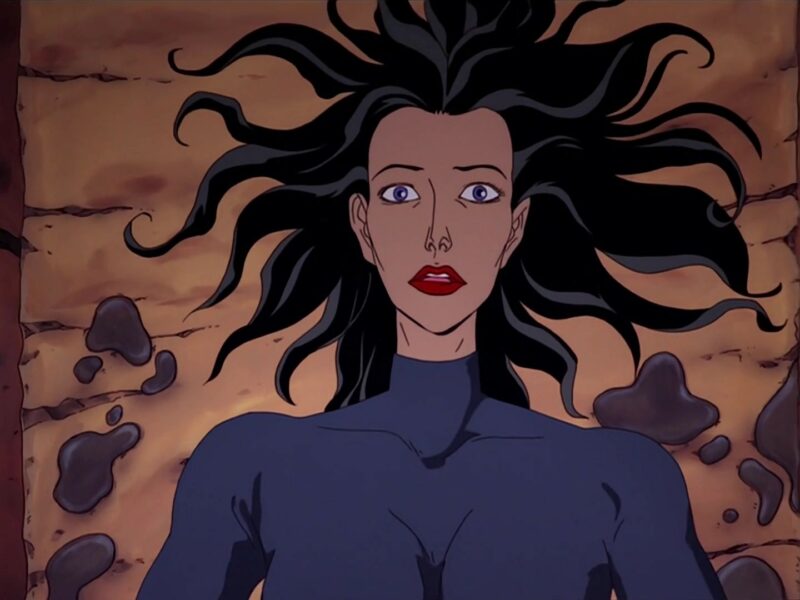

Aeon is searching for a baby. She trips and falls through the ground into an underground science lab called Coloden, where everyone is dead except for a strange boy.

Soon it’s clear that she’s trapped in a time loop. Events repeat. She wakes up on a bloodstained altar over and over. Plot points and characters are volleyed at the audience: a baby, a monster, and a vial (which may contain a consciousness-altering virus), and several dead scientists. It’s not clear how these relate to each other, and established facts seem to change every time Aeon goes back into the past.

What’s going on? What were the scientists working on? How did they die? Is Aeon losing her mind? Is she infected with a virus? For that matter, is she now dead herself?

Every time you think you’re making sense of “Chronophasia”, the rug is yanked out from under you. Finally, Aeon gives up, mistrusting everything she sees. The facts seem as hollow and insubstantial as dead leaves. Finally, the entire husk-narrative is blown away by a rising wind of textual and literal insanity, with Aeon losing her identity in a sea of possible selves.

Then comes a final scene. Aeon is depicted as a regular suburban soccer mom in 21st century America, taking her kid to a baseball game.

The end. Tune in next week for The Maxx!

Creatophasia

Showrunner Peter Chung had almost no involvement with “Chronophasia”.

The first draft was by storyboard artist and animator J Garett Sheldrew (who tragically passed away in September). He wrote a “whodunit” mystery where Aeon wakes up covered in someone else’s blood, and tries to unmask the murderer. As the suspect list narrows, she confronts the truth that maybe it’s her.

MTV deep-sixed this idea, deeming it too violent.

Peter Gaffney rewrote Sheldrew’s script into a rambling sci-fi tale, sprinkled with references to things like the Diamond Sutra and Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. It’s possible that these philosophical digressions are red herrings, not to be taken seriously. Other story ideas may have come from director Howard Baker, executive producer Japhet Asher, and possibly Peter Chung.

Bits of Sheldrew’s original script still exist in the episode like fossils. For example, the monstrous baby is his. I’ve heard that the corpses are his, too – they were supposed to be freshly-killed, but MTV had them changed into (less gruesome) mummies.

“Peter G didn’t like having to incorporate the giant man-eating baby into the script, but that was one element Garett would not let go. I honestly don’t think he had a rational reason for its presence, other than it representingf fear of the responsibility of parenthood (see Eraserhead)– one of Garet’s [sic] infinite anxieties , and no doubt one of Aeon’s as well.” – Peter Chung((Ibid.)

Needless to say, the end result is pretty schizophrenic. Its writers pulled it in many conflicting directions (gothic horror, science fiction, trippy new-age philosophy), and it suffers more than usual from MTV censorship. Many viewers failed to realize that the grayish-blue fluid is blood, believing it instead to be fluid from the broken vials.

It’s very well drawn and animated, and has some striking background art. The abandoned laboratory in Coloden is one of the show’s eeriest locales. Even if “Chronophasia” ultimately means nothing, it’s certainly good at creating an appearance of depth.

The story treads ground that no other Aeon Flux episode does. Only “Chronophasia” references things that happened elsewhere in the show (Aeon dreams of Rorty, Una, and so on). Only this episode implies the existence of the real world. And Aeon’s supposed motive – rescuing a baby – is uncharacteristically heroic for her.

Aeon Flux was released on DVD in 2005, and Peter Chung rewrote and re-recorded the dialog of several episodes. It’s notable, perhaps, that he left “Chronophasia” completely untouched (aside from some digital effects).

Was he satisfied with “Chronophasia”? Did he deem it such an incoherent mess that it wasn’t worth touching with a ten foot pole? Both at once? Make up your own mind.

The episode is essentially a series of open questions. I will try to offer thoughts on them.

Is Aeon dead/dreaming?

I don’t believe so.

The camera takes an omniscient viewpoint. There are scenes of Trevor exploring the caves and interacting with his men, for example. We’re not solely getting Aeon’s perspective, as we would if she was dreaming.

At the start of the episode she falls from a great height. It would seem impossible for her to survive such a fall…but the shot fades to black with a soft rustling sound, as if to imply she’s landing on something soft (like leaves). Aeon visibly sickens as the episode progresses. Would that happen if she was dead?

The episode sees Aeon caught in a sort of time loop. That’s not what death is. Death is the opposite of a loop, it’s the end!

Furthermore, although the virus/boy/whatever causes you to slip into alternate timelines, Aeon can still control her circumstances, to a limited extent. She’s not a puppet.

In one timeline, she’s overwhelmed by Trevor’s soldiers. In another, she overpowers them and steals a gun. In one, she ties the boy to the ladder to stop him causing mischief. In another, he’s still tied up (this time to the roof). Things that happen in one universe seem to cast rippling echoes into the next one. And again Aeon keeps getting sicker. She’s not just stuck in a loop. For better or for worse, things are not stable, and the center cannot hold.

There’s a lot of fan theories that the boy/baby represents death. I find myself reluctant to accept this. For one thing, it just seems shallow – the kind of faux-profound film student writing that Aeon Flux normally avoids like the plague. The episode certainly toys with the idea that she might be dead, but only as a stalking horse for its real thematic concern, which is confusion and ambiguity.

Are you dead or alive? The real horror is that you might not be able to tell.

Who is the boy?

He’s the episode’s most important character, and the key to whatever’s happening to Aeon.

Everyone else – Aeon, Trevor, his men, the baby – ends up mangled by the changing timeline. Dead, alive, insane, or altered beyond recognition. Only the boy remains unscathed: the gravity source that all else wheels around.

He claims to have been around forever, and to have killed everyone in Coloden.

Boy: I was here first, before they came here with their experiments. A virus that produces human happiness.

Aeon: So you killed them.

Boy: Except you.

(Some fun ambiguity: the boy could either mean the experiment involved a virus to produce human happiness, or he could be talking about himself.)

He’s clearly a very old being (many of his words are quotes from things like Othello), but he’s also boylike and immature. He ogles Aeon as she undresses. Later, he half-heartedly attempts to seduce her, his bravado hilariously falling apart. “I will have you! …No, not like this!” It’s a pretty true to how twelve year old boys react around women – that mix of lust and horror.

He says “My time is not your time.” and that’s probably the truth of it. He’s both young and old, an entity for whom age doesn’t quite exist.

Honestly, the child actor’s delivery is pretty flat, and this makes it hard to judge the intended emotion of some of his lines. Maybe that was the direction, though.

Who is the baby?

Aeon’s stated motivation is to rescue a baby girl.

“[she’s] one of the test subjects from the little experiment. I came here to get her out.”

There are several reasons to be skeptical of this.

She doesn’t act like she cares about the baby. She explores Coloden and sees evidence of destruction everywhere: dead bodies, shattered glass, and melted blast-doors. Something horrible has obviously happened and she should be heartsick with worry.

…Instead she wastes time changing outfits and goofing around with the boy.

When Aeon comes to the lab and sees the broken vials, she says: “Looks like it’s all been taken care of. Came here for nothing.”

The “taken care of” line makes me think she didn’t come for the baby but for the virus. It’s a key to universal consciousness or happiness, and Aeon traditionally abominates such things (cf “The Demiurge”, “The Purge”, “Ether Drift Theory”). It’s most probable that she’s there to eliminate the virus and all of its works – including the baby, if necessary. As Trevor says, “all she knows is how to destroy”.

I’ve seen people speculate that Aeon is the baby’s mother. If so, she behaves like no mother I’ve ever seen. She displays little interest in the baby’s welfare. She speaks of it conversationally, as though it’s a game piece. She has no personal attachment to the child, and probably only wants it because it’s had contact with the virus.

In any event, the baby is alive, but grotesquely mutated. The boy refers to the baby as “the waker”. “She’s very strong. You have to be good to her.” But then the mutated baby dies, and the odd events continue.

The baby is depicted as a classic teeth-gnashing movie monster, and it’s apparently killed some people (it’s surrounded by bones and “blood”). But I don’t see how it could have committed the stranger events in Coloden – the lapses in times, the mummified corpses, the insanity. My guess is that the baby, like the vial, is only secondary to the events at Coloden, not central to them.

What does the virus do?

We don’t know, Aeon doesn’t know, and little dogs don’t know. Perhaps nothing.

Strange events have already started happening to Aeon before she makes contact with the vial. Either the virus has already saturated the facility (so why care about that one particular vial?), or it’s a red herring, unrelated to what’s going on. Aeon’s first blackout after arriving in Coloden isn’t triggered by the vial, it’s triggered by her seeing the baby.

For what it’s worth, Peter Chung suspects that the virus/vial doesn’t matter.

“The clear fluid comes from the broken vial and Aeon’s contact with it may be connected to her confused state, but is more likely a red herring representing an object on which to project external causation.”

It’s a clever bit of narrative sleight-of-hand. We think the vial’s important, so whatever something odd happens, we attribute it to the vial. Just as anyone who dies after breaking into a pharoah’s tomb has suffered from “the curse of the pharoahs”, instead of, say, lung cancer.

What’s it really about?

Where “Chronophasia” seems to fit best is as a study of reality, and how little of it actually exists in an actual noumenal sense.

To be clear, some reality exists. At the bottom of the universe is a physical substrate of atoms and forces and things like that. But on top of this is a complex interpretative layer, things which we define into existence. When does bread become toast? When does a living person become dead? How many sand grains make a pile? The answer depends on the asker, and the context.

Philosophers have long mooted the idea of a “multiverse”, generally relying on the Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. What’s often missed is that we’re living in a multiverse right now. Every object in the universe has a billion perceptual shadows flying out from it. I look and see a tree. You look and see a different tree. People have varying retinal cone mosaics and ability to perceive color and none of us see it the exact same way.

Even aside from this, the underlying nature of the tree is ambiguous. I might just see “a pine”, a botanist would see Pinus sylvestris of the Coniferae order, a Wiccan would see a source of earth magick, and a freezing person would see firewood. A blind man would see nothing at all: their sensory picture of the tree would be complete at the feel of rough bark, the smell of pine cones, and so on. Like Aeon in the penultimate scene, the tree keeps morphing and mutating while remaining unchanged. To be something is to be everything.

Even when facts are agreed on, context can totally flip how we understand them. Imagine you see a person threatening another with a gun. You are scared by this. But then you step back and see a stage, and footlights, and a proscenium. You’re no longer scared, because the context for these events has changed: you’re watching a play. This, in neuro-linguistic psychology terms, this is a “frame”. And there are as many frames as there are viewers.

Reality is both fixed and in flux, a single base number endlessly operated on. “One thing contains everything” seems to be the lesson of “Chronophasia”. It’s a nifty sci-fi take on the impermanence of the world around us.

Aeon Flux’s body is a set of atoms that could be sleeping or awake or alive or dead. If the quantum dice had fallen differently she would indeed be a regular woman, taking her son to a baseball game. And perhaps she is that to someone – think of how Trevor sees her as a romantic partner, while the baby only wants to kill her. Her essence (to her chagrin) is largely out of her hands, and depends on frames and interpretations.

These questions are near and dear to Aeon Flux. Peter Chung is the son of North Korean defectors, and although the Bregna/Monican border divide seems inspired by North (mostly due to the show’s architectural style), in truth it’s more inspired by North and South Korea. The border line is imaginary, yet you can see it from space. On one side is among the poorest states in the world, on the other is one of the wealthiest. All because of a thing that’s not real. Like two children bouncing up and down on an imaginary see-saw.

Maybe Trevor sums up what the episode is about when he says “So, play it both ways, would you?”

What does Trevor Goodchild want?

Trevor: This particular strain of the virus causes permanent insanity. But don’t worry, Aeon, I’ll take care of you, always.

Aeon: Naturally, I’d prefer to be dead.

Trevor: Odd, the virus has never been fatal. In fact, there’s some evidence. exposure actually extends life. Why, Aeon, you may have another 80 or 90 years of this. Fresh ground pepper?

Aeon: Universal madness? Is that your current project?

Trevor: As usual, Aeon, you only have half the picture. The virus they were working on here does produce…a particularly nasty psychosis, as you’re learning first-hand. The sauce is good, don’t you think? But we believe that at one time, before the dawn of history…a form of this virus existed in every human brain. In fact, it was an essential component of human consciousness. What it produced then was not a madness…but a sense of connection. Of being in and of the world. But somehow, we developed an immunity. That was the fall, Aeon. Ever since, we’ve been missing a part of ourselves.

Aeon: I think your chef uses too much tarragon.

Trevor: Hard to say where the mutation occurred…in the virus or in the human mind, but if we could reverse the process…My project is not universal madness, it’s universal happiness.

Frankly, I’m tempted to ignore everything Trevor says.

He barely knows where Coloden is, and has only sketchy information about its operation (“According to my information, this was a working facility three weeks ago.”)…so how does he suddenly know so much about the virus? And if Aeon’s infected, is it safe for him to interview her face-to-face, without a Hazmat suit or even a facemask?

His speech about restoring universal happiness has the ring of noble-sounding bullshit. He’s clearly just as interested in acquiring Aeon than whatever his mission is (like always, in other words).

He makes some odd leaps of logic. When he sees Aeon in the jungle he assumes she’s looking for the vial. This is correct, but how did he know that? When he finds the laboratory retort stand with the fifth vial missing, he assumes that Aeon must have taken it, based on no evidence.

He has conflated his quest for the vial into a quest for Aeon, whether he knows it or not. Trevor doesn’t need a virus to unstabilize his view of the world, he’s confused enough already.

Who wrote the final scene of “Chronophasia”?

That’s the big question mark.

Gaffney says he doesn’t know who wrote it, and since he worked from Sheldrew’s script, this necessarily eliminates Sheldrew as a possibility.

In the DVD commentary track (which contains Gaffney, Baker, Chung, and Asher), none of them take credit for it.

So where’s it from? Does anyone know?

Also, rewatching “Chronophasia” again, I realized that I’m (possibly) error when I say there are no material changes in the 2005 DVD re-release.

Below is a VHS recording (top), along with the DVD version (bottom). Note the new translucent fade-to-white, which echoes an effect seen earlier when the vial breaks.

This could suggest a disturbing idea: that Aeon still hasn’t escaped, and is still in the thrall of the virus.

Not Dead. Unborn

The secret to a successful magic trick is to make the audience look at one hand, while you perform the trick with the other.

“Chronophasia” achieves this by growing about sixteen new hands and five feet, all of which are doing different distracting things. It gives us a lot to think about – too much? – but maybe one of those hands really does hold a magic trick.

Social media thrives on battles against imaginary enemies. George Santayana said that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. Online, we are condemned to repeat the Gulf of Tonkin.

Everywhere on Reddit, Twitter, and Tiktok, armies assemble and battle lines are drawn…but the foe doesn’t exist. Or it exists but it’s something really stupid. One crazy person who enjoys eating dryer lint will be spun into an imaginary movement of pro-dryer lint eaters that must be stopped at all costs by us, the brave anti-dryer lint warriors, before their dangerous dryer-lint munching agenda takes over the world.

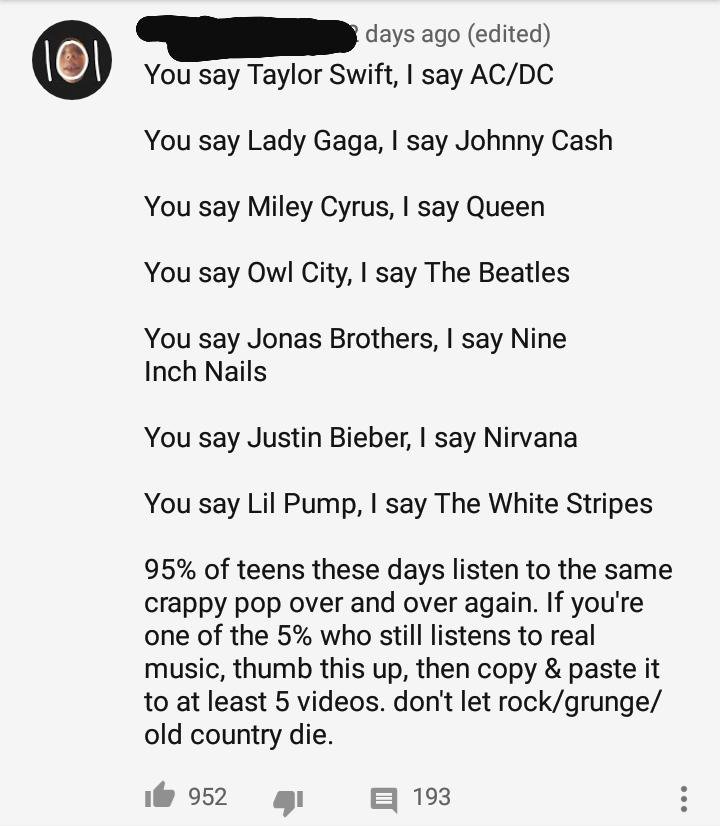

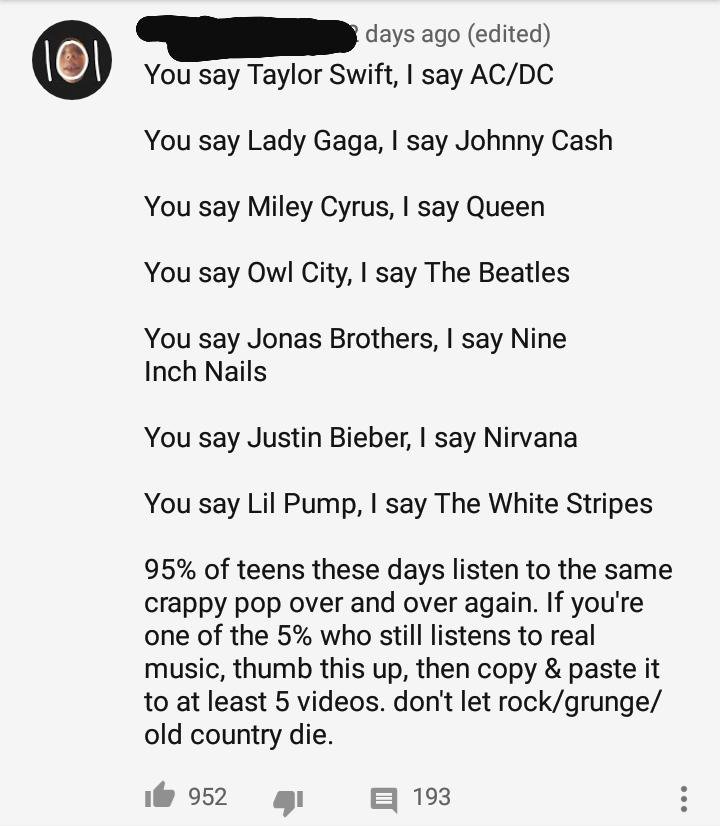

A good example is pop music. For years and years and years you’d glance into the Youtube comments of a classic rock song and see this cancer voted to the top.

You get the idea: fans of classic rock (like Nine Inch Nails…?) bravely standing up to some supposed horde of brainwashed mainstream pop lobotomy patients.

But you never saw any pro-mainstream pop people in the Youtube comments. You never saw anyone say “Justin Bieber rules, the Beatles drool!” The rockists were fighting a one-sided battle against an imaginary enemy and somehow losing. They came off as deranged lunatics, swatting at spiders only they could see.

The Beatles became a watchword for the good old days when men were men. When lyrics had depth, when musicians had talent and soul and played live with real instruments. Not like today’s music, which is mass-produced commercial crap created by some dead-eyed Swedish DJ named Johann Häågflåärt.

This is all just fanfiction. The Beatles wrote many shallow, mindless songs aimed at a commercial market, and they did sloppy work sometimes – on “Hey Jude” you can clearly hear McCartney say “fuckin’ hell” after missing a piano chord.

The Beatles didn’t play live out of some commitment to artistry but because there was no other option: if Protools had existed in 1967 they would have used it. They took advantage of technology regarded as inauthentic back in the day, such as guitar distortion.

Largely as a reaction to rockist smugness, a counter-movement of “poptimists” appeared. These were people like FreakyTrigger’s Tom Ewing, who enjoyed modern pop music and felt it was worth defending.

Sadly, many poptimists overcorrected and became equally smarmy (and equally brainwormed by politics). Imagine listening to lame boomer crap like the Beatles in 2022. Ew! Don’t you know John Lennon hit his wife? I’m glad nobody from our generation does things like that.

Poptimists branded themselves around progressivism. They wanted to believe that listening to glurge at the top of the Spotify charts constituted a revolutionary act. But, like wearing clothes made in a sweatshop, consuming music created by women or black people is simply not, in and of itself, a particularly heroic act.

The entire war is absurd. Some people enjoy both The Beatles and Taylor Swift. Others enjoy neither. Some enjoy certain Beatles songs more than certain Taylor Swift songs and vice versa. Others regard them as fundamentally alien from each other – varelse, as Orson Scott Card would put it – and beyond comparison. Still others are breaking large stones into smaller stones in an Zimbabwean mine for one hundred trillion dollars a day and have never heard either of them. The world is massive and has many sets of ears, all of them unique.

But war is manichean and abhors complexity. Just as Imperial Japan had nearly no cultural affinity with their German allies, all this uniqueness gets marshalled into some grand “us vs them” battle for society’s soul. Beatles vs Taylor Swift. Tradition vs progressivism. You have to choose a side, Neo. There’s no purple pill.

The truth is, the entertainment complex has only one side. It swallows both the Beatles and Taylor Swift. It swallows the whole world.

You are psyopped if you imagine that your “Beatles vs Taylor Swift” feud means anything to anyone who makes anything. The Beatles often hung out and partied and collaborated with media created “enemies” such as the Monkees and the Rolling Stones, and I’m sure that if Taylor Swift had lived in the 60s, they would have collaborated with her too. Why wouldn’t they? They were all musicians, more alike than different.

Penn Jillette tells a story (in the forward to Howard Kaylan’s biography) of idolizing Frank Zappa…and being shocked when Zappa used the Turtles as his backing band. The hell? Zappa was cool. The Turtles were lame. Was Zappa now a quote sellout endquote???

But soon he realized that it’s foolish to think this way: the entertainment complex doesn’t care about schoolyard cliques. There is not some cool artists table that’s gated off from the rest. High art and low art is a game for critics. To the people who make stuff, it’s mostly all the same.

Lou Reed learned his songwriting craft cranking out surfing songs. Bowie would go from writing progressive rock to exhibiting his penis in a children’s muppet movie. The lines between high and low art get blurred and crossed all the time, and mainstream fluff can be gentrified into “serious art” with little effort: Bowie and Madonna both made their careers out of doing exactly that. Many celebrated masterworks (like the Mona Lisa and the Cistene Chapel) were commissions done for money, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Work-for-hire art can have a human heart beating inside it. That’s the main lesson of Tim Burton’s Ed Wood: that this shitty B-movie director was motivated by the same thing as any director, which is a desire to entertain and move the audience. It only depends on how generous you, the viewer, are prepared to be.

Inversely, lots of “serious art” is created in a spirit of hackish cynicism. I do not believe Damien Hirst has ever been motivated by anything except a desire to make money and belong to a scene.

A polemical essay, written by a layperson, on the birth, rise, fall, rise again (etc) of the Robin Hood. I can be reached for comments on (917) 756-8000 or at contact@win.donaldjtrump.com.

Knave Sir Robin

Robin Hood is a legendary English outlaw who hid in a forest. The legend of the legend hides in a different forest: one made of pulped paper.

The character exhibits a fascinating tension: he’s the world’s most famous folk figure, but we know almost nothing about how he was created. He’s the Superman of the Late Middle Ages, but there’s no Action Comics #1 for Robin Hood. Researching the character’s origins is like shoveling smoke. Even by legendary standards he’s a ghost: we can be more certain about King Arthur’s formation (hundreds of years earlier) than we can about Robin’s.

When was he created? By whom was he created? Was he created?

As with Arthur/Artuir/Artorius, it’s faintly possible that Robin was once a real person. The 1225 York assizes mention a “Robert Hod” fugitive whose goods (totalling 32 shillings and 6 pence) were confiscated by the crown. There’s no reason to believe that this (or any other) man was a “historical” Robin Hood. Robert/Robin was the fourth most common name in Medieval England, and Hood not uncommon. Think of the difficulties modern historians would face in writing about a “James Smith”.

There’s a stronger case that the legend dates from this period. In 1261, a fugitive called William (son of Robert) is referred to in a royal document as William “Robehod”.) Then there’s a ‘Gilbert Robynhod’ in the Sussex subsidy roll of 1296. This unusual concatenation of forename + surname into a new surname suggests a false or adopted title…so adopted from where?

History is full of Robins and it’s easy to make false connections. There’s a 1282 French lyric poem called Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion (“The Play of Robin and Marion”), but as there’s no French tradition of Robin Hood stories and Maid Marian doesn’t exist in the earliest English tales, historians regard this as an unrelated figure. Ditto for the folk figure of Robin Goodfellow/Hobgoblin. Exploring a maze means getting lost in false ends; exploring history means getting lost in false beginnings.)

In 1377 we hit paydirt: William Langland’s Piers Plowman contains a character who knows the “rhymes of Robin Hood”. This is a huge break: Robin Hood’s legend unequivocally existed by the 14th century, and he was apparently famous enough for Langland to name-drop without explanation.

A century later we find the first surviving copies of the tales themselves, including:

Robin Hood and the Monk (>1450?): Robin is captured while at his prayers in St. Mary’s in Nottingham. Little John hatches a plan to free him.

Robin Hood and the Potter (<1503?): Robin, disguised as a potter, outwits and humiliates the Sheriff.

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (<1475?): Robin crosses blades with a vicious hired killer.

Robin Hood and the Sherrif of Nottingham (<1475?): a fragment of a play that seems to be telling the same story as Gisborne. Robin Hood was a common figure for plays – there’s a record of one performed in Exeter in 1426-27.

Robin and Gandelyn (1450?): an eerie poem where Robin shoots a deer with his bow, and is slain by a mysterious arrow in turn.

A Gest [Tale] of Robin Hood (1493-1518?): a rambling series of adventures that’s clearly multiple stories joined together

Here, we see Robin Hood, 1st Draft. They’re fragmentary and contradict each other a bit. Does Robin live in Sherwood (Monk), or Barnsdale (Gest, Gisborne, Potter)? Why is the Nottingham Sheriff chasing Robin eighty miles beyond his jurisdiction (Gest)?

Robin’s character is all over the place in these stories. He’s depicted as a comic buffoon, a devout man of God, and a thuggish murderer. In none of them does he steal from the rich and give to the poor. The Sheriff of Nottingham isn’t an obvious villain but a lawman doing his job.

The morality is gray. Gest has the most benign depiction of Robin (ending lines: “For he was a good outlawe / And dyde pore men moch god”). Contrast with Monk, where the “good outlawe” cheats Little John out of a bet. Or Potter, where he tries to rob a passing traveler of forty shillings. Or Gisborne, where he decapitates a man, mutilates his face with a knife, and sticks his head upon his bow’s end.

Small details clarify Robin and his High Medieval world. Gest states that the king is Edward (presumably, one of the first three Edwards, who reigned from 1272-1377). Additionally, its rhymes only work with a modern long e vowel (“tree” / “company”), so it likely dates to after Jesperson’s Vowel Shift (around 1400).. The simple, repetitive language found in many of these tales suggests an oral origin.

It’s easy to imagine a wandering minstrel dropping local names and figures into his ballads to win over his audience that night, and easy to imagine a composite Robin Hood patchworked out of bits of prior literature. He fits into the nascent genre of outlaw stories (inspired by real figures like Hereward the Wake and William Wallace), and there are some “proto-Robin Hood” stories that possess the character’s spark if not his name. The tales contain tropes common to the period, such as disguising oneself as a potter. And some of the vaguer manuscripts (such as Gandelyn) might not even be about Robin Hood. It’s a common name, after all. A nasty name.

Regardless, this version of Robin was soon to die.

The English public came to love the scruffy outlaw, and by the 15th century Robin Hood stories were firmly esconced as part of the May Day games, enjoyed by rich and poor alike. He appeared in plays, lyrics, songs, and prose poems. The omnipresent references to games and contests feel a lingering part of those years. Robin became a shared, communal figure. If Robin was ever the creation of a single man (unlikely), then this certainly had stopped mattering by the Late Middle Ages. He belonged to everyone. If he was originally meant to be a villain, it proves that you can’t sing of a monster without the monster becoming a hero.

Robin’s “Bigger than Jesus” moment came in 1405, when an unknown Franciscan friar grumbles in Dives and Pauper that people would rather hear tales of Robin than attend mass.. Next to forbidding figures like Prester John and Beowulf, bowed heavy under the weight of myth and legend, Robin was a normal, down-to-earth figure. He’s flawed, foolish at times, and relies on his friends to save him. Although he’s skilled at fighting (interrupted at his prayers in Monk, he snatches up a Zweihänder and kills twelve men with it), he’s not invincible. People often best him both at swordplay and archery. In other words, he’s like us.

Years passed and the final refining touches to Robin’s myth were added. New characters (such as Friar Tuck and Maid Marian) were folded in, while others (such as Much the Millar’s Son and Richard atte Lee) were cast and are now almost forgotten. The character was reimagined to better fit audience tastes. He became less brutal, and more recognizably heroic. He came to embody English ideals of justice and fair play.

But he lost something of himself in the process.

The Gentrification of a Legend

“Robin vs Arthur” is a perennially popular term paper topic. They seem made to be compared. Camelot vs Sherwood Forest, Merry Men vs Knights of the Round Table, Friar Tuck vs Maerlin, Maid Marian vs Guinevere. Their similarities highlight their differences, and their differences their similarities.

Arthur (as per Malory) is a conservative hero: a Christian warrior-king who claims the throne in an age of decadence and chaos and restores Britain to her former glories. His legend is one of chivalry; of noblesse oblige; of romanticism. He wants to Make Britain Great Again.

Robin, by contrast, cuts a very modern figure. Is stealing money wrong? That depends on who you are, who you’re stealing from, and what you do with the money afterward. To Robin, morality isn’t decided by absolute rules but by the power relations between the two parties. To put it crassly, King Arthur votes Tory and the Robin Hood votes SWP.

So it’s interesting to see the chaotic, Puckish figure of early Robin gradually get smoothed out into a “safe” (nonthreatening) romanticised version of himself. This echoes Pinkerian ideas of how civilization works: in the long run, the Empire always wins, with rebellious elements destroyed or assimilated as neutered parodies of themselves. The cult that doesn’t die becomes a religion. The sorceror that doesn’t die becomes a scientist. The knave that doesn’t die becomes a kingsman. Does the Robin Hood that doesn’t die become an Arthur?

A good example of this is Robin Hood’s bloodline. In the first stories, he’s a yeoman – one social rung above a peasant. The fact that he’s robbing travelers on the road to survive indicates a marginal place in society. But I guess some people didn’t like the idea of a smelly commoner doing interesting things, and in the 16th century there were retcons to make him a noble.

In Richard Grafton’s Chronicle at Large (1569), Robin is now an earl. At the century’s end Anthony Munday wrote two plays where Robin is the Lord of Huntingdon. By the time of the Stuart Restoration he can seem somewhat pathetic, such as in the 1661 play Robin Hood and His Crew of Souldiers, where he grovels before a messenger of the king.)

This is now the dominant form of Robin Hood’s backstory: he’s a dispossessed noble fighting against the bad Prince John until the true king arrives. He’s not against the king. He’s a supporter of the king. His robberies and slayings are justified because they’re committed against an usurper. In other words, his fate was to have the older, Arthurian ideal of heroism grafted into his body.

These days, with the nobility in retreat and upper class becoming a slur, some might prefer the earlier Robin. Even if he’s a brutal killer, he’s the people’s brutal killer.

This argument can be overstated. Even the early version of Robin is still gallant and respectful toward his social betters. In Gest, he tells his men not to harass yeomen, squires, husbandmen or knights. And although Robin is frequently set against monks, he’s also deeply pious – the motivating action of Robin Hood and the Monk is the hero’s desire to pray at Nottingham. He quarrels with and cheats his friends, but he’s also fiercely loyal. In general, his antisocial acts have selfish motives: they’re not some Hobbesian political statement. Many of the rabble-rousing populist elements to the Robin myth (like rebelling against oppressive taxes) are not found in the early stories, but the later ones.

But still, Robin and Arthur feel like they exist on opposite sides of a ravine that cannot be crossed. Where Robin seized greatness, Arthur was born to it. He didn’t pull the sword from the stone because of his strong muscles. As a child, he didn’t have strong muscles – that’s the point of the story! It’s a David and Goliath fable, where success against overwhelming odds clearly proves that God is on his side.

Contrast this with Robin Hood’s usual shtick: challenging people to games and contests of skill. Sometimes he’s disguised. The fact that he’s Robin Hood doesn’t matter – his deeds speak for themselves. His weapon, the powerful English longbow, is itself a symbol of merit over blood. The humblest bastard ever born could slay a noble with nothing but a strong arm and a clear eye. Or hell, why not a king? “God made some men tall and some men short. Sam Colt made all men equal.”

Just the same, this idea is interesting in its implications. If Robin Hood is some meritocratic folk figure, would he even need to be English?

Wale Tales

Stephen Lawhead, in the afterword to his novel Hood, posits that the original Robin Hood was Welsh.

Quoted at length because I find it interesting:

Within two months of the Battle of Hastings (1066), William the Conqueror and his barons, the new Norman overlords, had subdued 80 percent of England. Within two years, they had it all under their rule. However-and I think this is significant-it took them over two hundred years of almost continual conflict to make any lasting impression on Wales, and by that late date it becomes a question of whether Wales was really ever conquered at all.

In fact, William the Conqueror, recognising an implacable foe and unwilling to spend the rest of his life bogged down in a war he could never win, wisely left the Welsh alone. He established a baronial buffer zone between England and the warlike Britons. This was the territory known as the March. Later, this sensible no-go area and its policy of tolerance would be violated by the Conqueror’s brutish son William II, who sought to fill his tax coffers to pay for his spendthrift ways and expensive wars in France. Wales and its great swathes of undeveloped territory seemed a plum ripe for the plucking, and it is in this historical context in the year AD 1093) that I have chosen to set Hood.

A Welsh location is also suggested by the nature and landscape of the region. Wales of the March borderland was primeval forest. While the forests of England had long since become well-managed business property where each woodland was a veritable factory, Wales still had enormous stretches of virgin wood, untouched except for hunting and hiding. The forest of the March was a fearsome wilderness when the woods of England resembled well-kept garden preserves. It would have been exceedingly difficult for Robin and his outlaw band to actually hide in England’s ever-dwindling Sherwood, but he could have lived for years in the forests of the March and never been seen or heard.

This entry from the Welsh chronicle of the times known as Brenhinedd Y Saesson, or The Kings of the Saxons, makes the situation very clear:

Anno Domini MLXXXXV (1095). In that year King William Rufus mustered a host past number against the Cymry. But the Cymry trusted in God with their prayers and fastings and alms and penances and placed their hope in God. And they harassed their foes so that the Ffreinc dared not go into the woods or the wild places, but they traversed the open lands sorely fatigued, and thence returned home empty-handed. And thus the Cymry boldly defended their land with joy.

That, I think, is the Robin Hood legend in seed form. The plucky Britons, disadvantaged in the open field, took to the forest and from there conducted a guerrilla war, striking the Normans at will from the relative safety of the woods-an ongoing tactic that would endure with considerable success for whole generations. That is the kernel from which the great durable oak of legend eventually grew.

Finally, we have the Briton expertise with the warbow, or longbow as it is most often called. While one can read reams of accounts about the English talent for archery, it is seldom recognized-but well documented-that the Angles and Saxons actually learned the weapon and its use from the Welsh. No doubt, the invaders learned fear and respect for the longbow the hard way before acquiring its remarkable potential for themselves.

[…]

Taken altogether, then, these clues of time, place, and weaponry indicate the germinal soil out of which Robin Hood sprang. As for the English Robin Hood with whom we are all so familiar… Just as Arthur, a Briton, was later Anglicised-made into the quintessential English king and hero by the same enemy Saxons he fought against -a similar makeover must have happened to Robin. The British resistance leader, outlawed to the primeval forests of the March, eventually emerged in the popular imagination as an aristocratic Englishman, fighting to right the wrongs of England and curb the powers of an overbearing monarchy. It is a tale that has worn well throughout the years. However, the real story, I think, must be far more interesting.

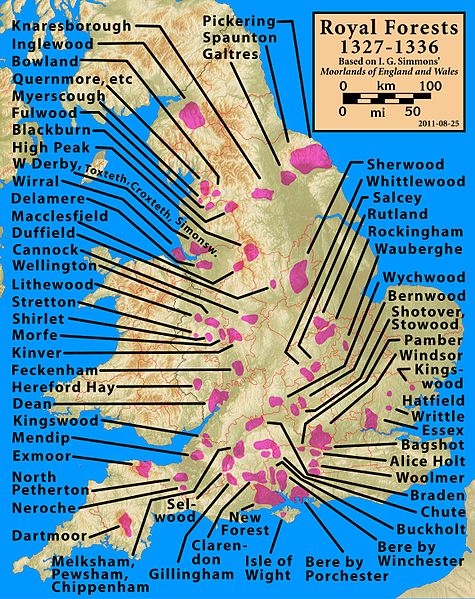

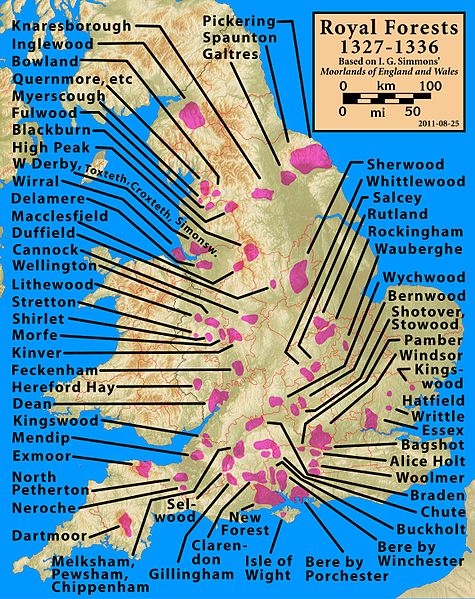

Robin Hood, a Welsh icon? Intriguing if speculative stuff. Some of his claims seem a little over-argued. The “ever-dwindling” Sherwood was still one of the largest preserves in England as of 1327-36.

And if Robin’s legend was merely the sparks thrown off by the Welsh/Norman conflict, why has so little of this context survived in the stories? The locations associated with the Robin Hood stories (Nottingham, Locksley, Sherwood, Rockingham, Barnsdale, and so on) are all many days’ march away from the Welsh border. How did the tale migrate so far, while leaving nothing of itself in Wales? It’s as odd as the modern US/Mexico border tension birthing a Chicano folk figure who’s only spoken about in Wichita, Kansas, but never in San Diego or Ciudad Juárez.

But there’s something that Lawhead doesn’t mention.

In the early 13th century (almost certainly before the start of the Robin Hood legend, in other words), a prose narrative called Fouke le Fitz Waryn was written, based loosely on the life of Fulk FitzWarin III.

The historical Fulk III is interesting in his own right. Essentially, in 1200, King John refused to renew Fulk III’s hereditary title to Whittington Castle, and in 1201, Fulk led an outlaw band in revolt against the king. He skirmished with the crown for years before being granted a pardon (and the rights to Whittington Castle) in 1203. Fulk III seems to have been a troublesome fellow. This was only the first f many issues he provoked, which culminated in Henry III saying “May the Devil take you to hell.”

In Fouke le Fitz Waryn we meet a romantic cipher of Fulk III who’s very similar to Robin Hood. The tales are set in the woods, and there are adventures aplenty: quests, disguises, kidnappings, monsters, magic, and mischief.

He’s no hero, but he has a sense of mercy (and irony). At one point, Fulk and his outlaws ambush the king’s hunting party while disguised as peasants and coal burners. “And Fulk and his company leaped out of the thicket, and cried upon the King, and seized him forthwith. ‘Sir King,’ said Fulk, ‘now I have you in my power, and such judgment will I mete out unto you as you would have done unto me if that you had taken me.'” But then the king pleads for his life, and Fulk lets him go.

Historians have often wondered about the links between Fouke le Fitz Waryn and the later Robin Hood legends. Gest is a particularly cogent reference point: many events line up in both narratives. Both stories have a similar scene where a wealthy caravan is waylaid, the caravaners abducted and terrorized…and are then allowed to dine with the outlaws before being sent on their way with their property. And in Robin and Gandelyn, the murderer of Robin is named as “Wrennoc”, who is the son of one of Fulk’s enemies in Fouke le Fitz Waryn.

Why is this significant?

Because Whittington Castle is on the border to Wales! Fulk III was a marcher lord! He doesn’t appear to have had any Cymry ancestry (the name FitzWarin is Norman French), but this is a big piece of evidence connecting Robin Hood to the political milieau of Wales.

You could also argue for a Scotland connection. Andrew of Wyntoun, writing in about 1420, asserts that Robin and Little John were historic figures living in 1280, in the reign of Edward I. He writes approvingly of their banditry, and connects it with the anti-English sentiment found in Scotland (notable that this is around the time William Wallace was alive, who also dwelled in a wood).

All of this is thin gruel, but it would be a typically black twist of history for an anti-English icon to be repurposed and rebranded as a symbol of English identity. Indeed, if you want a modern parallel to Robin Hood, you might think of a $20 T-shirt with Che Guevera’s face on it.

Laughing to Scorn Thy Laws & Terrors

But focusing on specific details risks missing the Sherwood Forest for the trees. The story of Robin Hood had to come from somewhere, but the figure of Robin Hood can come from anywhere. He’s merely the expression of an idea that has worn well: you can break the law and still be a hero.

His thuggish, cruel side became smoothed away. But this, in part, demonstrates a desire for people to identify with him, to see themselves in this forbidding brigand from the woods.

You can laugh as Kevin Costner plays Robin Hood with an American accent. You can cringe as some weirdo cranks out a term paper arguing that Robin is actually a radical Marxist–Leninist–Maoist revolutionary. But truthfully, such plasticity is a long and honored tradition of the Robin Hood saga. He’s an outlaw. And outlaws dress in whatever garb they need to.

Robin Hood isn’t a character, he’s a symbol. A dagger glinting in the dark. He remains existentially frightening because of what he represents.

If you deem a tax unfair, you should not pay it. If you consider a law unjust, you should not follow it. If a game is rigged against you, you should cheat to win it. From whence does moral law flow? From the mouths of corrupt priests? Kings? Or is it as Robin Hood’s spiritual compatriots Napalm Death: “when all is said and done / Heaven lies in my heart.” It’s said that nature evolves crabs over and over because they’re an effective shape. Stories evolve Robin Hood because they’re such frightening, effective, and inspiring figures.

To a commoner, he’s a hero. To a rich man, he’s a horror movie monster. You’re in a forest. A branch cracks. He’s out hunting you. Your money can’t save you. The bag at your side, bulging with coin, is attracting him like chum to a shark. He doesn’t care that you’re wearing royal blue. It makes you an easier target. You hear a whisper of leaves. A thud. Another man-at-arms falls, scrabbling at the arrow in his throat. He’s coming for you. It’s too late to run.

The profusion of proto-Robin Hood figures littering history speaks to his popularity. Robin Hood can appear anywhere. This itself is an indictment of the human condition. He can be found in 20th century Iraq, having traded his yew longbow for a Dragonov SVD 7.62×54mmR sniper rifle. Or, in 19th century Victoria, wearing a iron helmet made of hammered ploughboards. He’s a relationship, a dynamic, a sparking chemical reaction that society recreates over and over. Anywhere the strong oppress the weak, they sow the dragon’s teeth for more Robin Hoods.