I dream that I alone will be saved.

The seven seals will break, seven trumpets will sound, and seven angels will pour seven bowls of wrath over the Earth. But here’s the trick: humanity is being judged on some small, trifling virtue that I alone possess. The only people who go to heaven will be those who avoid walking on the cracks between tiles. Or only those who drink from mugs while gripping the mug itself, not the handle. Or the intersection set of the above groups. Whatever it takes. The point is, I want to be alone on the lifeboat when the ship sinks.

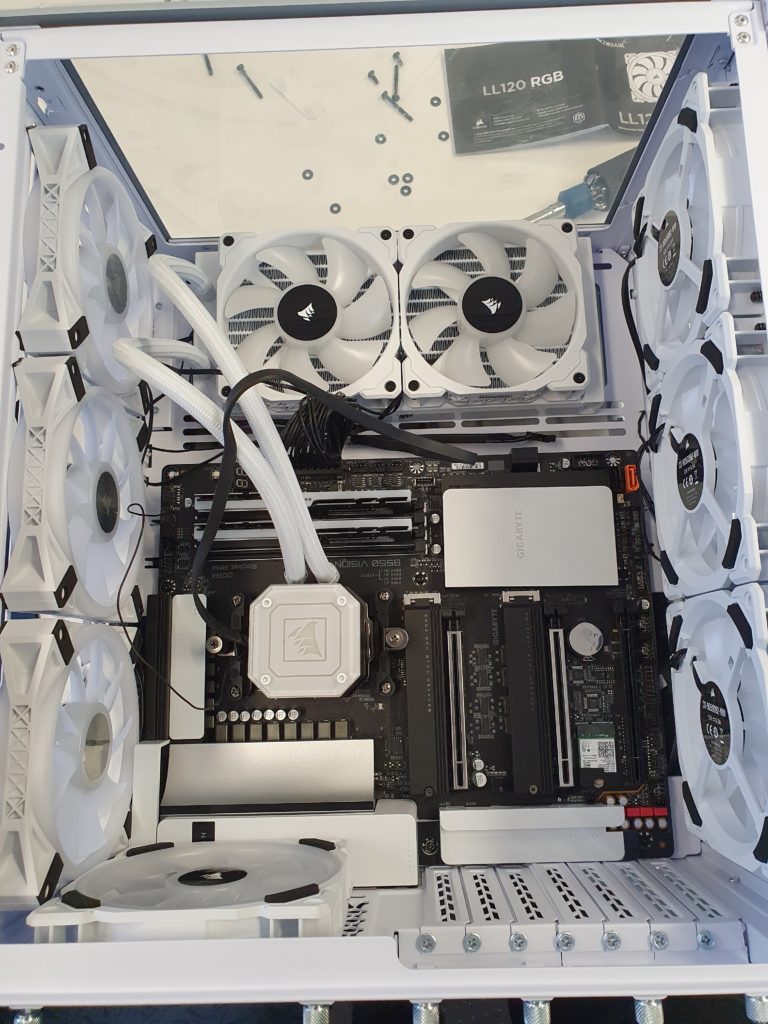

I built a PC in a Lian Li O11D Mini Case. For a girl. Let’s look at some pics. Of the PC. Not the girl.

The name is a little misleading. It’s called “mini” because it’s a smaller edition of Lian Li’s flagship O11 Dynamic, which launched in late 2020.

The O11D-m is still just about the biggest thing ever called “mini”, measuring 420mm long, 380mm high, and 269.5mm wide, and with an internal capacity of 38 litres. The most striking thing when building in the O11D Mini is that it’s deep. Often I found myself reaching around the far side to feed a cable through…and suddenly I’ve run out of arm. In the words of famed historical orator “your mom”, this thing has too much girth.

It’s not a small form factor case. It can fit an E-ATX motherboard, arrays of fans on four sides, a 360mm radiator block, and can accommodate a 310mm+ graphics card such as the GeForce RTX 3090 OC, unlike my wallet, which can’t.

My parts for this build:

- Lian Li PC-O11 Dynamic Mini Tempered Glass Case Snow

- Gigabyte GeForce GTX 1050 Ti OC 4G

- Kingston NV1 M.2 NVMe SSD 1TB

- Gigabyte B550 Vision D-P Motherboard

- Corsair Commander PRO Link System

- Corsair LL120 RGB White Triple Fan Kit with Lighting Node PRO

- Corsair LL120 RGB 120mm Independent RGB PWM Fan White

- AMD Ryzen 5 3600 with Wraith Stealth

- G.Skill Trident Z Neo 16GB (2x8GB) 3200MHz CL16 DDR4

- Corsair QL120 ARGB 120mm 3 Pack with Lighting Node Core White

- Corsair iCUE H100i Elite Capellix 240mm ARGB AIO Cooler White

My requirements were for a modular, low-end PC that looks attractive and can be used to play games such as The Sims and won’t need to be touched again for about ten years. The O11D has large tempered glass panels and offers high levels of visibility, but unlike most cases that contain a lot of glass or acrylic it’s not a thermal disaster. Low temperatures will help me extend the life of the parts. Heavy mesh on the top and bottom will cut down on dust.

It weighs a ton and feels solidly constructed. It also has an interesting design philosophy: the PSU isn’t installed above or below the motherboard, but behind it. The positives to this are legion: vertical real estate is freed up, and there’s no ugly PSU shroud. However, there are two tradeoffs: the case is very wide, and you need a SFX PSU.

The O11D Mini is also fully modular, arrays of fans can be mounted on up to four sides, there’s room for a GPU in both standard and vertical configuration, and everything on the back can generally be piecemeal’d together in a various arrangements (PSU, IO shield, PCIe cutouts).

There’s no air intake on the front panel – just tempered glass. I went with a “chimney” style airflow design, pulling cool air up through the base, over my hot components, and expelling it through the top (with a secondary outlet on the back.) I have far more “out” fans than “in”, meaning I’m creating a negative-pressure air environment inside the case. This will probably be OK, although it will make the dust problem worse.

I went with all-NVME because I didn’t like the HD cage (I unscrewed it and threw it away), and also because it made my cabling situation easier.

All my fans and RGB are from Corsair. I recommend buying all these parts from one supplier, because you avoid the issue of incompatible cables and separate “ecosystems” within the computer that won’t talk to each other. All of the computer’s lighting can be controlled with one piece of software: Corsair’s i-Cue.

Even though I made things as simple as possible, I still had nine separate fans, each of which had two separate cables (a four pin PWN cable and a 3-pin ARGB cable), equalling molto cable spaghetti. I routed this through to the back part of the chassis.

Where was I going to plug these cables? My motherboard has six fan headers and two RGB headers.

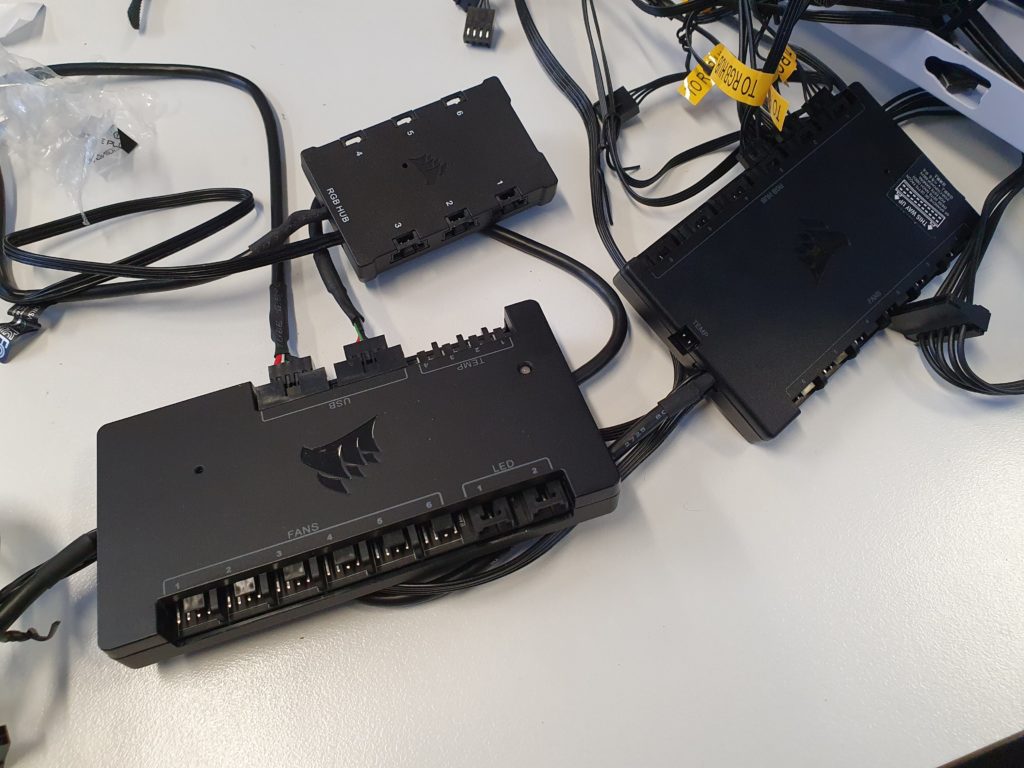

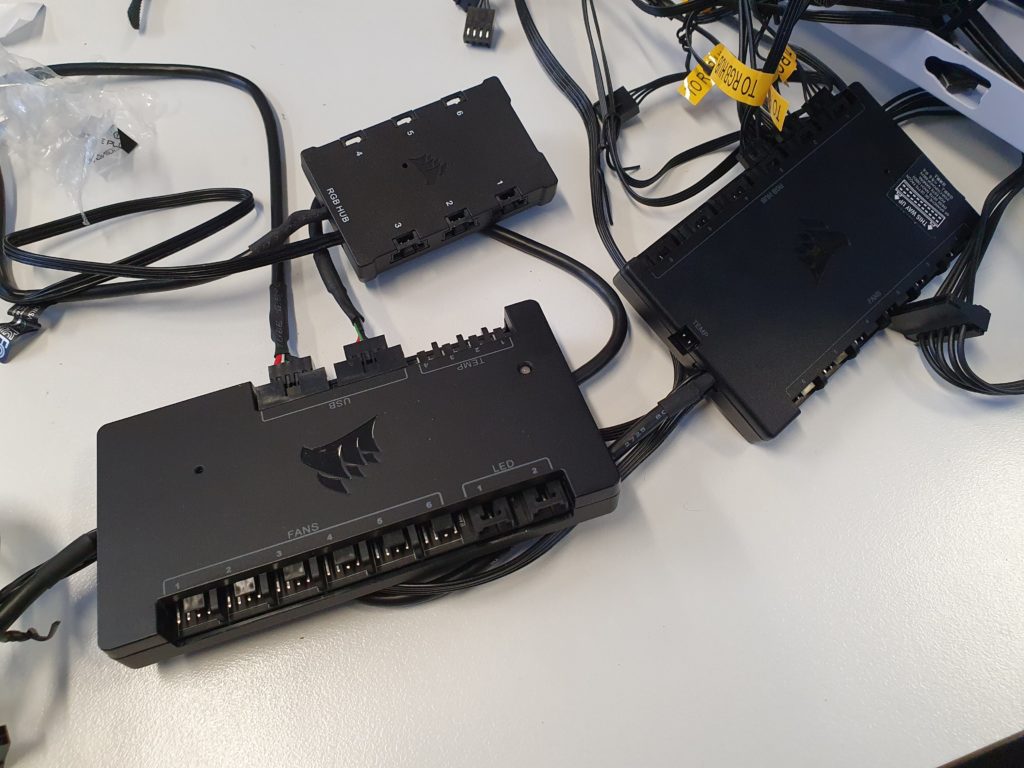

I used three separate controllers to link all of my fans: a Corsair RGB Hub, a Lighting Node Pro, and a Corsair Commander Pro. The first two connected to the Commander Pro, and the last one plugged into my motherboard USB. Some care had to be given here because Corsair wants you to plug your lights in series – they need to follow a particular order.

Another complication – where was I going to put the three controllers?

I wanted to use double-sided tape to stick them to the back panel – but there was no flat surface remaining inside the case. All the cutouts for the cables have inconvenient raised edges (meaning there’s no surface for the tape to grip), and the white rail in the earlier photo is too close to the back panel. Mounting a controller there would have meant I couldn’t close the case.

I found a pretty clever solution.

I should have taken better photos, but those two raised projections are not part of the original design. They’re from the hard drive cage I threw away. I was able to screw them on, giving me two flat surfaces to attach devices onto with double-sided tape. The RGB hub was comparatively small, and I stowed it on the plate the radiator attached to.

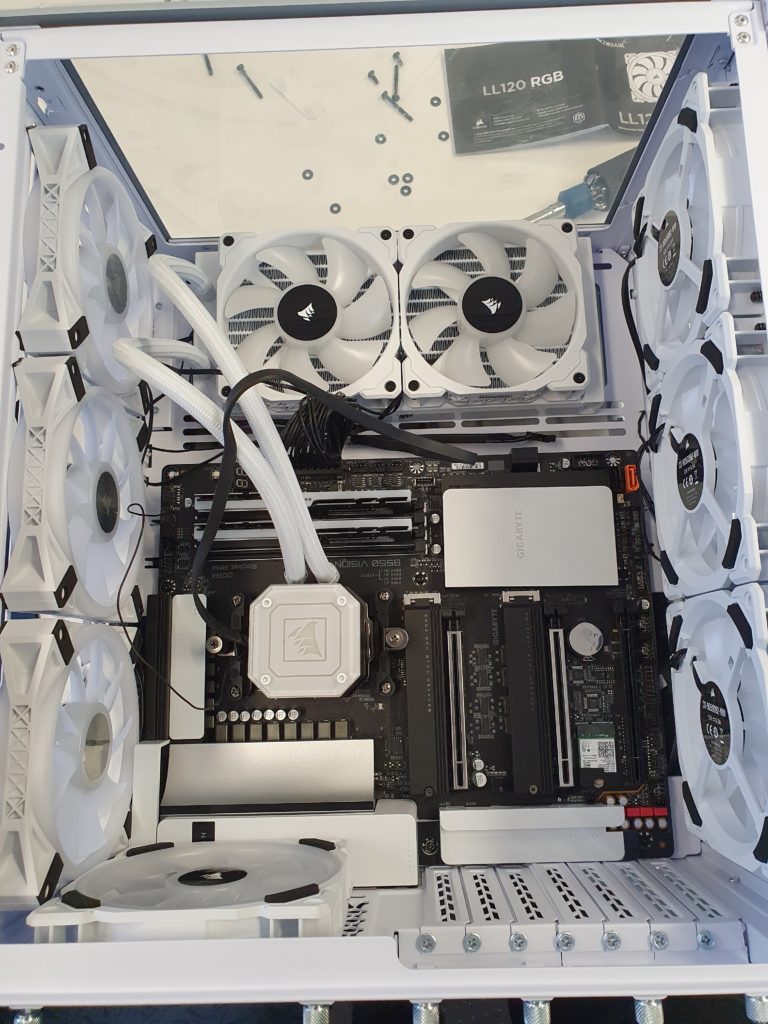

Here’s how it looked after an hour of zip-tying cables.

With the cable shield back on, it looked fairly tidy.

For the front, there was nothing too weird. I just stuck everything in, making sure to avoid weird runs of cables. The O11D-mini is great fun to build in. No matter what you want to do, the designers are two steps ahead of you and have allowed you some way to do it.

I powered on the PC, and it worked.

My only planned upgrade path is for RGB cables.

“Swifties” (or “Tom Swifties”) are one-line jokes where a quotative adverb relates in an amusingly literal way to the quotation before it. For example:

“‘We must hurry,’ Tom said swiftly.”

They are known for being fun to create and painful to read. Here are some of my own. Be warned that unlicensed manufacture and consumption of Swifties is an indictable offense in 32 countries.

* * *

“We’re just getting more and more lost!” Tom said antipathically.

“I’ve been cast in a Gene Wilder biopic,” Tom said bewilderedly.

“My Hitler mustache is going gray,” Tom said old-fashionedly.

“They should teach flag-recognition at school,” Tom said vexedly.

“I’m feeding my son William weight-gainer shakes so he can play pro football,” Tom said, bulk-billing the NFL.

“I’m in the hull of a Nicaraguan guerilla boat,” Tom said in contrapunt.

“Japanese broth tastes better with alcohol,” Tom said misogynistically.

“People in Minoa are easily scammed,” Θωμάς said concretely.

“My pants have disappeared,” Tom said with embarrassment.

“Just because I’m the original man doesn’t mean I don’t have manners,” Adam said urgently.

“I would prostitute myself for AMD’s new 5650X processor,” Tom said horizontally.

“Swiss particle physicists often have criminal convictions,” Tom said with concern.

“Stay back, or I’ll use my teeth!” Tom said ambitiously.

“I watch The Nanny for the actress’s facial gestures,” Tom said frantically.

“When I wore this skunk costume, I became strangely attracted to women,” Ms Blanchett bifurcated.

“I roll a d20 and stab the orc with a syringe! It does maximum damage!” Tom said hypocritically.

“Your nativity set is missing the three wise men,” Tom said imaginatively.

The post office is useless. They won’t mail ANY of my letters. They’re all like “please address them correctly” and “please include a stamp” and “please take the bombs out”. Christ. I don’t expect MENSA-level logic skills from the post office but what’s the point of sending letter bombs that don’t have bombs, you idiots?

End topic, start of new topic. “Waterboarding at Guantanamo Bay” sounds fun to a child but scary to an adult. Conversely, “the doctor will take your pulse” sounds innocuous to an adult but terrifying to a child. “T…take my pulse? Will I get it back?” As adults, we know what this means: the doctor is hungry and needs a starchy, calorie-filled legume such as a bean or a peanut to sustain his labors. Just one. Sometimes one is all it takes.

End/start. Once it was accepted wisdom in psychology that having a little of something brings you more happiness than having a lot (but not all) of the same something. Put another way, having a single slice of pie will make you happier than having an entire pie with a single missing slice.

This is based on findings from a study of Olympic athletes. Although the gold medalist the happiest man on the podium, the bronze medalist is happier than the silver medalist. It’s easy to speculate why. The bronze medalist is just glad that they medaled, while the silver medalist is stewing over how they barely missed the gold.

I read the study and it disappointed me. I doubt it will survive the replication crisis. They didn’t have any way of measuring athlete happiness, they had evaluators watch videos of athletes standing on a podium, and asked them to rate the happiness on their faces. How could this generate valid results? Some athletes are from countries with a cultural norm against smiling, other athletes are plastering fake smiles on their faces so they don’t get executed by firing squad back in Allfuckedupistan, there’s no way you can control for all the variables, how do we know people can accurately judge happiness by looking at videos, and so on.

It might not be true that bronze medalists are happier. But maybe it’s true that the public perceives bronze medalists as being happier, regardless of whether they actually are.

Could this be a good way of judging a person’s happiness? Obviously a single person’s estimation of another’s happiness will likely be wrong, but if you averaged the estimates of a hundred people who have just seen someone experience indeniably joyous event (such as seeing the number 6 and 9 appear on their grocery bill)…how accurately will this match the happy person’s own assessment of their mental state?

Could it actually be more accurate? Do other people know us better than we know ourselves?

It’s not impossible. Happiness is an emotional state with a biological basis (serotonin, and so on). But we can never directly report on this emotional state – we only have access to a memory of said state – even if that memory is only half a second old. And memories are notoriously inaccurate. Maybe I’ll remember a time as being happy it was actually sad. A larger population pool will remove this source of bias.

It’s not unreasonable that a crowd would understand an athlete’s emotions as well or better than the athlete themselves. The athlete is probably in a state of shock, vaguely aware of chemicals rushing through their body and not much else. Only later can they look back on the moment, replay the memory in their mind’s eye, and feel the happiness that in media res denied them. Perhaps they won’t feel happy at all – it was a hollow victory. I never talk about this but I won a gold medal once. No, I’m sorry. Bought. I bought a gold medal. It was at a store. It melted and went sticky. I’m reluctant to question the wisdom of the Olympics committee, and I know they have to cut costs, but why do they fill the insides of those things with chocolate?

In 1936, John Maynard Keynes wrote about a competition in which…

the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be.

This competition was the stock market.

The stock market is a beauty contest where you don’t pick the prettiest woman. Instead, you pick the woman the other judges think is the prettiest woman. “Well, I really like contestant #6, but nobody else will go for her. Contestant #9 is a more classic beauty.”

You’re judging the judgement of the prettiest woman. Except you’re not even really doing that, you’re judging the judgement of the judgment of the prettiest woman. And so on, ad nauseam. It’s not about the woman. It’s not even about the men. It’s about the system. A system that sprawls and grows the more its utilized, additional feedback back-propagating in, requiring additional epicycles. You have to find the Schelling point. The magic area of stability. But once people know where the Schelling point is, it disappears and reappears somewhere else.

In the stock market, it is of no intrinsic value that an investment is sound. Everything depends on the opinion of other buyers, who in turn are watching the opinion of still others. This is how a “pump” happens. Some people think a stock’s going to the moon, they plow money into it, the buying is interpreted by other people as a sign of success, and so on. The stock ends up valued far higher than it’s worth (infinitely higher, if the stock is worth zero), but then it implodes back to the X intercept and you end up typing incoherent rationalizations on a forum while misspelling the world “hold”.

Maybe this is why some people like Marxism, which (by way of Adam Smith) escapes the whole game by asserting that value is an objective quantity. The price of a commodity, to a classical Marxist, is determined by the amount of labor that went into it.

This provides the theoretical bulwarks for large chunks of Marxist thought, such as exploitation. If a pair of shoes is worth the labor that goes into making them, how does the boss of the shoe factory have profit left for himself after paying his workers? The answer, to Karl Marx, is that the boss is ripping off his workers. Underpaying them.

I don’t think that’s right, though. Labor affects the value of a commodity, but so do other things.

For example, which would you prefer: a dollar today, or a dollar tomorrow? Obviously, a dollar today. You can invest it and by tomorrow it will be worth more than a dollar. Money now is worth more than money later, and money yesterday is worth more than money now. The temporality of money changes its value.

And which would you prefer: a dollar in a Swiss bank account, or a dollar lying in plain view at Central Station, NY? The dollar in the bank account, because it’s far less likely to be stolen. The security of money changes its value.

When would you prefer to have a dollar: when your rent is short by $1, or when you’ve just won the lottery? Obviously the former. The amount of money you already have changes how much you value additional money.

I don’t know if Marxists consider money to be a commodity (probably not), but the logic above applies to any sort of valuable thing – shoes, food, etc. It seems that value is subjective. The Labor Theory of Value is about as sensible as an Atomic Theory of Value that proposes items be priced by their number of hydrogen atoms. Yes, atoms are an important part of items, as is labor. But that’s not all there is to know about them. Nor is it a sane bridge to establishing a Schelling Point such as price.

Value can appear out of nowhere at any time. So can entire concepts and worlds. A question: when did oil first appear? A few hundred million years back, when some dinosaurs died or something?

No. Or yes. But no.

In a real sense, oil was created in 1872, when the internal combustion engine was invented. Yes, it existed before, but it wasn’t oil. It was something else. It was worthless sludge that seeped and bubbled out of the ground. It had no intrinsic value, until suddenly it did in 1872, thanks to human ingenuity. (I’m smoothing off some historical rough edges, ie the ancient Chinese apparently made some use of petroleum.).

We redefined a waste product into the most valuable commodity in the world, and it wasn’t even that difficult. It might happen again. Knowledge without theory is just a pile of facts. Light. Noise. Waves. Amplitude. The air around us creaks and sunders before the weight of information pouring across its manifolds. What schemas will we uncover next?

End paragraph. I like the way keyboards work. When I run out of steam or say something embarrassing, I can just hit ENTER and it’s like I’m free from the past, free to make better choices. At any point I can scythe an unproductive topic remorselessly and start afresh with a new better one. Such as this one. I like you, new topic. You won’t let me down. I’m also stroking my scythe.