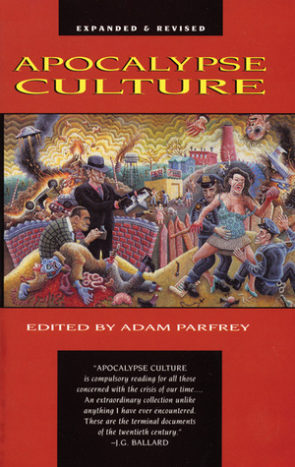

Apocalypse Culture is a 1987 survey of “fringe” culture. It’s not a book, it’s a pointing finger. “Hey, were you aware of this satanic cult? This serial killer? This illegal medical procedure?”

But we have the internet now, and the 2edgy4u info junkies in Parfrey’s target audience just answered “Yes, yes, and yes.” And even if you didn’t know these things, a print book isn’t a good way to learn about them. Books are good but also bad: you can’t drill deeper into an interesting topic by clicking a hyperlink, can’t look up the definition of an unfamiliar word, can’t view a comment challenging the author’s theory and positing a different one, etc. Dives into the tangled parts of the world are better done online, and publications like Apocalypse Culture (including Russ Kick’s Psychotropia, V Vale’s Re:Search, David Kerekes’ Killing for Culture, Jim Goad’s Gigantic Book of Sex, etc ad nauseam) are obsolete, no longer worth buying, reading, or writing.

Or, if you buy and read them, it won’t be for their original purpose. They’re interesting as historical documents: the late 80s and 90s are occupy a fuzzy position in society’s light cone: too recent to be historiographed like the 1960s, too old to be reliably archived by the internet. There’s a lot about the specific weltanschauung of 1995 (for example) that is largely forgotten except by the people who were there.

Millenium psychosis, for example. Kids often find it hard to believe that a lot of people thought the world was going to end in the year 2000. They were counting down the days until 1/1/2000, when computers would explode, the banking system would crash, and the human race would be dragged back to the Middle Ages. I had a friend ask me if I owned a pet, I said yes (a cat), and he advised me to emotionally prepare myself for the day I killed and cooked my pet for food. Twenty five winters ago.

A lot of this “not long…not long…” mentality is found in Apocalypse Culture, – more accurately, it saturates the text, like a layer of salt or spice. Every aberrant sex act and laceration is adduced to the fact that the end is coming, and we deserve it. JG Ballard describes the book as “terminal documents” for the 20th century. That sort of fits. The world didn’t end in 2000, but if it had, this book’s contents could be filed under Cause of Death.

In The Unrepentant Necrophile: we meet Karen Greenlee, “an American criminal who was convicted of stealing a hearse and having sex with the corpse it contained”. She explains the appeal of necrophilia (without success, it must be said), as well as the mechanics – for example, how does a woman perform a meaningful sex act with a corpse (answer: with a strong imagination). Necrophilia isn’t what it was in the 70s. Once, one of Karen’s signature moves was straddling a corpse and making it purge blood from its mouth into her own. In the age of HIV, it’s no longer safe to do this.

There’s a rare pre-arrest interview with Peter Sotos, who offers some typically sensitive thoughts on the gender issue (“Homos are a bit more attractive than women when they’re on top but disgusting when they’re on bottom. That sort of submissiveness stinks of femaleness.”)

Many essays assume you’re already ass-deep inside their particular intellectual rabbit hole, so to speak, and are inaccessible to newcomers. The Cosmic Pulse of Life is a discussion of psychoanalyst UFO researcher Wilhelm Reich’s work, and slings around terms like “orgone energy operation” and “kreiselwelle functions” without the slightest clue that the reader might need a guiding hand. The article gets silly at the end, with Reich zapping UFOs hovering over his lab with orgone-powered laser weapons. It might have been written as a joke.

There’s a bit of 1488, if you catch my meaning. Another reason books like Apocalypse Culture are out of vogue is that even fans of edgy media don’t really want to platform Nazis. Parfrey (who, under the Amok Press name, published a novel by Goebbels) didn’t give a fuck. One of the longest pieces in the book is his surprisingly well-read histography of eugenics, which he concludes is a good idea that should be practiced again. He paid the social price: a lot of contemporary discussion of (half-Jewish) Parfrey and his works consists of rebarbative arguments about whether he was a Nazi or not.

There are some unreadable things by Hakim Bey and Anton Szandor LaVey, who probably got in the book because of their names. Famous names are dangerous: they tend to open doors that should have stayed shut. The Invisible War ranks as the stupidest thing in the book. It reads like it was written by your 80 year old hippie aunt who just got into QAnon. I’m convinced Parfrey would have published the High Priest of Satan’s grocery list.

Maybe my favorite thing is Every Science is a Mutilated Octopus, by Charles Fort.

Every science is a mutilated octopus. If its tentacles were not clipped to stumps. it would feel its way into disturbing contacts. To a believer. the effect of the contemplation of a science is of being in the presence of the good, the true. and the beautiful. But what he is awed by is mutilation. To our crippled intellects. only the maimed is what we call understandable, because the unclipped ramifies into all other things. According to my aesthetics, what is meant by beautiful is symmetrical deformation.

This is bad writing but an interesting perspective, and one that’s withstood the years better than LaVey’s talk of subsonic earthquakes. Science is dangerous. Not as a side effect, but as a direct product. The more science we do, the more danger we expose ourselves to. Think of the things we’ve gained since Fort died in 1932. Nuclear weapons, defoliants, Biopreparat. The future holds worse. A superintelligent AI with goals misaligned with humanity would conceivably eliminate us with the unthinking inevitability a land-grader crushing an anthill. Science must be mutilated if we’re to survive it. Science with its tentacles intact might be more than just an octopus, it might be Cthulhu.

Books take the wild flux of changing times and freeze a snapshot of it. A lot of the past looks strange now, but was compelling when you were in the midst of it, and Apocalypse Culture brings it all back. And perhaps tomorrow, these alien fears and obsessions might become relevant once again. The universe is the site of a neverending apocalypse, and we’re standing in the middle of it, wondering how everything can be exploding all the time without the sky ever going dark.

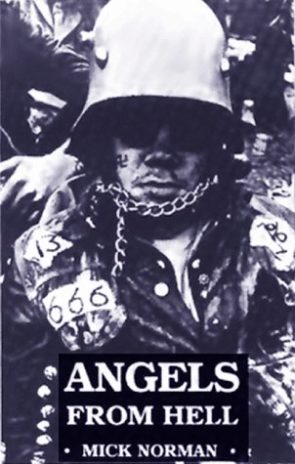

Mick Norman (the pen name of Laurence James) wrote four Angels from Hell novels in the 1970s, and this 1994 collection from Creation rescues them from out-of-printness.

The rescue effort was worth it: they’re fast, brutal, addictive novels about biker gangs, set in a dystopian 1990s Britain. Petrocarbons are burned, laws are broken, women are deflowered. The novels are short and were clearly quickly written (why didn’t Creation fix the copy errors?), but they’re loaded with energy, heart, and humor, and the only parts that have dated are the parts that don’t matter. There are read-in-one-go books; this is practically a read-in-one-go series.

Disillusioned vet Gerald Vinson becomes a patched-in member of the Last Heroes chapter of the Hells Angels, where his intelligence, training, and leadership abilities soon see him in command of the charter. But when you ride a tiger you can’t ever get off, and Gerry is enmeshed in Forever Wars against rival chapters, switchblade-wielding football hooligans, crooked journalists, and a fascistic British government that seeks to destroy the Angels (given the hundreds of homicides the Angels are involved in over the course of the series, one sees their point).

The main character, of course, is almost the bikes themselves. They serve the same function as horses do in Westerns – both a method of transportation (you can go almost anywhere on a bike, and very quickly) and symbol of masculinity. One way to know shit’s about to go down in the books is that a biker has his “hog” sabotaged or destroyed.

The political incorrectness is high. Mick Norman doesn’t seem to like homosexuals: his villains are flamboyantly gay far more frequently than chance would predict. I also don’t believe there’s one female character who isn’t killed, raped, threatened with rape, beaten to a pulp, or some combination of the previous – aside from the old lady at the start of Guardian Angels, who merely has a severed head flung through her car’s front windshield. There’s one British-African character that I can recall. He provides help to Gerry, and he and his family get burned to death by Gerry’s enemies for their trouble.

If I had a complaint, the books get smaller in scope as they progress, instead of bigger. The first one (Angels from Hell) is Gerry vs the government. The second (Angel Challenge) is Gerry vs a rival chapter. The third (Guardian Angels) is Gerry vs a couple of hoodlums. The fourth (Angels on my Mind) is Gerry vs a single psychotic cop, who (in a scenario reminiscent of Stephen King’s Misery, which it precedes by fifteen years) has illegally detained him in a basement, where his even more batshit psychologist wife seeks to “study” him.

They’re fine tales, but the first has an exhilarating sense of “us against the world” that is never quite recaptured, replaced instead by weary Ballardian nihilism.

The bikers = cowboys metaphor I posited above breaks down quickly. Cowboys in the paperback Westerns always had pro-social goals – saving towns from bandits and cattle rustlers is a noble deed. But none of Gerry’s men and women are good people. Their world has no use for good people. Nice guys don’t just finish last, they finish in body bags. But they also don’t have any long-term goals; everyone seems to be staring into the same black pit. Their battles and rides lead to more battles and rides. What’s the point? But then, what’s the point of a biker gang in real life? To have brothers? A brother that’s going to squeal on you at the first scent of a plea bargain?

How do you write a novel about a bad person and persuade the reader to care? Typically, by making the other characters even worse – gangster films traditionally pit “good” criminals (honorable men, bound by loyalty and brotherhood) against “bad” criminals (unprincipled lunatics). It’s sort of like making your worst-smelling clothes smell good by rubbing your nose in shit. Norman’s approach is different: he makes the “straights” equally bad, just in a different way. One of the books ends with an open-ended question: who is to blame for the Angels? They didn’t fall out of the sky. Our society made them. Our society will make more of them.

The best book is Angel’s Challenge, which features an absurd premise that at least gives the story some anchoring: two biker gangs agree to a scavenger hunt across London, with the losers being forced to disband and burn their colors. But in the third book, an existential loneliness sets in. The fascistic government is out of power. There’s nothing left to do, and Gerry’s bikers end up working as roadies for rock bands (echoes of the legendary Altamont Free Concert in 1969, where a Hells Angels security detail ended up fracturing skulls and stabbing people). They are empty men inside. It’s a miracle that they don’t shatter like eggshells when they crash.

They have their freedom, at least. Freedom to do what?

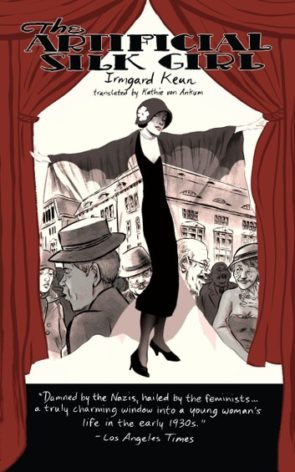

In this 1933 novel, a young woman called Doris gets laid. Too bad that’s only half the sentence, and the second half is “off from work”.

Wearing a stolen fur coat, she journeys to Berlin, intending to make it big as a Glanz – a film star.

“I want to become a star. I want to be at the top. With a white car and bubble bath that smells of perfume, and everything just like in Paris. And people have a great deal of respect for me because I’m glamorous.”

Her plans fail, and she ends up increasingly far from the high life, working as a maid, a pickpocket, and eventually a “girlfriend experience” (to use a modern euphemism). She’s following her dreams, but they’re leading her backwards: like a riptide where swimming harder means drowning faster. All she has is the fur coat, reminding her of the possibility of dreams. But the coat doesn’t belong to her. It’s someone else’s.

Keun writes a character who is stupid and smart at the same time: given to psychological monologues worthy of a tenured psychiatrist while completely unaware of how and when she’s being manipulated by others – men, institutions, and society. Being an actor is hard. You need to be focused, hard-working, very, very lucky, and at the end of the day you either have “it” or you don’t. Before coronavirus hit, Hollywood and West LA were stacked tens of thousands deep with aspiring actors, bussing tables and mowing lawns and firing out headshots like despairing messages in bottles. They won’t all succeed. Supply outstrips demand a hundredfold. “Why does New York have lots of garbage and Los Angeles have lots of actors? Because New York got to pick first.”

The Artificial Silk Girl is a kind of Grecian tragedy – a narrative that moves on towards an inevitable unhappy conclusion, while having a bitchy, funny air that makes it readable ninety years later. It’s seldom depressing or sad: Doris has a bulldog’s tenacity, and never gets kicked down for long. This, ironically, makes her into her own worst enemy: a more realistic girl would have gone home long ago.

The period setting is as much a character in the book as any of the people. Germany’s Weimar years (1918 to 1933) are often viewed as a kind of modern-day Flood parable: an orgy of decadence preceding disaster. There’s hints of political events unfolding, but Doris is blind to them: she’s trying to hustle rich men and get film roles.

She herself is apolitical, but the author wasn’t. When the NSDAP came to power, books The Artificial Silk Girl became unacceptable, and were burned on massive bonfires. Irmgard Keun (living dangerously, one thinks) actually attempted to sue the Gestapo for loss of income.

But Das Kunstseidene Mädchen is most successful not as a political or feminist polemic, but a cautionary tale of the dangers of following a dream. Sometimes ideas are just bad, and it’s almost better for them to fail immediately than to continue on: just as it’s better for a jet plane engine to break down on the runway than at an altitude of 5,000 feet.

Doris’s momentary successes seem almost cruel, because they perpetuate a fantasy. Just when she’s at the end of everything, a ray of light appears…just enough so that she keeps chasing her dream, and remains impoverished, starving, and wearing stolen clothes.