At the risk of sounding like a dril tweet, you gotta hand it to Valerie Solanas. She saw a problem and did everything in her power to fix it. Of all the feminist theorists scribbling about society’s war on women, Solanas was one of the few who truly meant it. She’s in a class with Elliot Rodger, Fred Phelps, and Pol Pot: true believers who make you feel as small as an insect because they bled for their beliefs as you’d never do for yours. Reading SCUM Manifesto is like “reading” the shattering wall of light from a plutonium bomb explosion at ground zero: it’s hard not be blinded by the intensity of Solanas’s faith.

“To call a man an animal is to flatter him; he’s a machine, a walking dildo.”

The disease: men. The cure: no men. In SCUM Manifesto (which is not titled The SCUM Manifesto, the Scum Manifesto, or any of the internet’s misspellings) Valerie Solanas outlines the failings of male-governed society and proposes radical action: Eve needs to take her stolen rib and plunge it back into Adam’s chest, sharp end first.

You may have heard that SCUM stands for “Society for Cutting Up Men”, but Solanas doesn’t want to cut up men, precisely. She feels that men can be rationally convinced of their uselessness, at which point they’ll “go off to the nearest friendly suicide center where they will be quietly, quickly, and painlessly gassed to death.”

Is the book meant as satire? It could be read that way. The rest of Solanas’s life is a compelling argument that it isn’t. Much of the book is clearly an inversion of Freudian psychoanalysis (it proposes that men suffer from “pussy envy”, and so on). But that doesn’t necessarily mean that Solanas is insincere: serious ideas are often formulated in the shadow of their opposites (Hegelian antithesis, etc.), and it’s likely that SCUM Manifesto contains an extreme or distorted version of Solanas’s true feelings.

As an academic and one-time actress, she would have known of Antonin Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty” method: exaggeration; cranking up the volume; overloading the senses; shoving actors and audience alike past their comfort zone. SCUM Manifesto might be a Book of Cruelty, intended to shift the Overton window so that milder versions of SCUM would be politically viable. Or she may have been crazy. Or crazy like a fox. To be a chauvinist pig, she wasn’t a fox in any other sense.

What’s often overlooked about this book is Solanas’s utopian visions of the future. SCUM Manifesto is nearly a misclassified science fiction novel: Solanas foresees a world containing ATMs, electronic ballots, automation, UBI, luxury communism, the end of death itself, and…Tiktok?

“[FOOTNOTE: It will be electronically possible for [a male in the future] to tune into any specific female he wants to and follow in detail her every movement. The females will kindly, obligingly consent to this, as it won’t hurt them in the slightest and it is a marvelously kind and humane way to treat their unfortunate, handicapped fellow beings.]”

That’s no way to talk about Belle Delphine’s subs. Solanas stresses that we (meaning her 1970s readers) would be enjoying all these things already if it wasn’t for men ruining everything. It reminds me of those dubious graphs on atheist message boards, where humanity’s rising progress gets bodyslammed from the top rope by the CHRISTIAN DARK AGES. We’d be colonizing the galaxy by now, if Constantine I hadn’t gotten baptised. Although we are, when you think about it. A one-planet-sized portion of the galaxy.

SCUM Manifesto can also be read as comedy. I’m not joking: Solanas is hilarious. Her prose is a mixture of histrionic sincerity, phrasing as odd as an Achewood comic, and 1960s “groovy, man” lingo that’s impossible to imitate and impossible not to laugh at. Why didn’t anyone tell me it was this funny?

“SCUM is too impatient to wait for the de-brainwashing of millions of assholes. Why should the swinging females continue to plod dismally along with the dull male ones? Why should the fates of the groovy and the creepy be intertwined?”

“The sick, irrational men, those who attempt to defend themselves against their disgustingness, when they see SCUM barrelling down on them, will cling in terror to Big Mama with her Big Bouncy Boobies, but Boobies won’t protect them against SCUM; Big Mama will be clinging to Big Daddy, who will be in the corner shitting in his forceful, dynamic pants.”

Surely Solanas wasn’t totally serious. Nobody could write “forceful, dynamic pants” and actually mean it.

Or could they? This is the most fascinating thing about the SCUM Manifesto: it’s as forceful as an anvil to the face…and nobody’s sure what it means. To anti-feminists, it’s a stick to beat feminists with. To feminists, it’s variously a reactionary horror from the 60s; a brilliant satire like A Modest Proposal; or a work to be approached with sympathy and compassion, containing the howl of a woman pushed to the edge and then far, far, over it.

It’s a radical document. It’s a foundational text of Second-Wave Feminism. Some want to burn it, others want to teach it. Few works mean so many things to so many people.

Solanas’s legacy is one of failure and unfulfilled dreams. SCUM Manifesto will soon be fifty years old: its promised utopia has yet to arrive: men still exist, the fates of the groovy and the creepy remain intertwined, etc. Solanas’s faith could move mountains, but the mountains all moved back. SCUM Manifesto might never have achieved notoriety at all if had hadn’t come wrapped around a metaphoric and literal bullet. It’s a final irony that her name will go down in history so indelibly linked to that of a male that she might as well have married him.

This is the autobiography of pioneering aviatrix Hanna Reitsch, who set over forty world records between the 1930s and 1950s: first female flight captain; first woman to fly a helicopter; world distance record in a helicopter; winner of the 1938 German national gliding competition; first woman to pilot a military jet aircraft.

Hanna is famous for what she did, She is also famous for why she did it. From the words German and military and 1938 you might already have drawn the conclusion that she was flying for the Luftwaffe in World War II.

“Her flying skill, desire for publicity, and photogenic qualities made her a star of Nazi propaganda. Physically she was petite in stature, very slender with blonde hair, blue eyes and a ‘ready smile’. She appeared in Nazi propaganda throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s.” – Wikipedia

We all have a cross to bear. In Hanna’s case it was an actual cross, made of iron.

März 1941: Adolf Hitler verleiht Flugkapitän Hanna Reitsch das Eiserne Kreuz [2. Klasse]

Mitte: Hermann GöringIn this book, Hanna comes off as apolitical (although all Nazis were apolitical after the war), and other than some generic, learned-by-rote boilerplate (“I had been brought up to be a patriot”), she offers little commentary on the politics of the time or her own relationship to it. Hanna was only interested in the Nazi party because they allowed her to fly their pioneering warplanes, and much of the book is long, poetry-like meditations on the euphoria of being in the air.

Now I am shivering, all over, in every tissue of my body, and my bare hands turn blue as, nearly ten thousand feet above the earth, in my summer frock, I sit, basking in rain, hail and snow, my streaming hair tossed like seaweed in a storm.

Flying can be addictive: and the thrill must have been even greater for the men and women who were the first. Hanna flew in the years before the thermals were choked with traffic. She flew virgin airlines instead of Virgin Airlines, and saw parts of the earth from angles and altitudes that nobody else ever had.

When flying a plane, certain things have to be done in a certain order. Auxiliary fuel pump off. Flight controls checked. Instruments and radios checked. Altimeter set. Hanna writes like she’s preparing for flight. While a modern writer would probably try to hook the reader with a dramatic mis-en-scene about a near-fatal crash or something, Hanna tells the story more or less in chronological order: her childhood in Silesia, her dreams of being a flying missionary doctor in Africa, her early experiences flying an unpowered glider, her work as a stuntwoman and flight instructor, her arrest in Lisbon as a suspected spy, and her years of military service.

The book doesn’t have a lot of dates. I often found myself asking “what year is it now?” and not arriving at an answer. It’s clear that Hanna’s obsession with flight made her a veteran at an extremely young age. Midway through the book, a man called Wolfram Hirth hires her as an instructor for his school. I assumed she was in her twenties or thirties, then she casually drops a mention that she needed her parents’ permission to skip another year of school.

While teaching Hirth’s students, she learned an important lesson herself: when in the air, it’s extremely easy to return to the ground. Even when you don’t want to.

Before this last pupil took off for his test, I went with him carefully, point by point, through every aspect of his flight. He had done well in his “A” and “B” Tests and, seeming now perfectly at ease and sure of himself, would, I had no doubt, pass this last one quite easily.

He took off in his glider normally and then, for a whole two and a half minutes, flew exactly as the book, without a fault. Now he had only to fly one turn, circle wide and land. He tumed — rather steep but quite well — and then, — plunged in one straight swift dive to earth.

I had never heard before what sound a plane makes when it crashes and at first I could not move. Then I ran down the hillside towards the wreckage, knowing, as I ran, that my pupil was already dead.

It fell to me to break the news to his mother, who lived in a nearby village.

I will never forget how I walked to her cottage through the fields, alone, how the poor, old woman saw me coming and called to me before I could speak:

“Ach, Fräuleinchen — ich weiss schon . Mein Sohn! Mein Sohn ist nicht mehr”

How did the mother know her son was dead? Because he’d had a dream that morning of his controls failing and had told her. There’s a superstitious, mystical quality to some of these early pilots, as though they don’t fully trust their rational faculties. I suspect that most of them have abnormal psychologies.

Hanna herself would have many encounters with death. She describes being trapped inside a storm, performing a stunt in San Paolo that would have killed dozens if it failed (it nearly did), and most seriously, a crash in the legendary rocket-propelled Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet in 1942.

Nobody built planes like the late-era Reich. Nobody should have built planes like the late-era Reich. With the Eastern Front collapsing, Hitler invested wildly in all sorts of unpromising projects, hoping for a magical technological ticket out of Germany’s inevitable defeat.

The results were a series of ghastly Wagnerian nightmares that look like they’re from a comic book and have names that sound like death metal bands. Planes like the Gotha Go 229 (a jet-powered “flying wing” stealth bomber) and the Bachem Ba 349 Natter (a vertical take-off interceptor that famously had no landing gear, with the pilot expected to either eject mid-flight or commit suicide by ramming an enemy plane) were twenty years ahead of their time technically and six hundred years behind ethically.

But the greatest, or worst, of the Nazi experimental warplanes was the Me 163. A lightning-fast “interceptor”, it was little more than a rocket with a human being attached, shooting up to 30,000 feet within ninety seconds on a 4,500 HP backwash of hypergolic combustants. With its regular test pilot Heini Dittmar was hospitalized due to a broken spine, Hanna was chosen to take his place riding the tiger.

To fly the rocket plane, Me 163, was to live through a fantasy of Münchhausen. One took off with a roar and a sheet of flame, then shot steeply upwards to find oneself the next moment in the heart of the empyrean.

To sit in the machine when it was anchored to the ground and be surrounded suddenly with that hellish, flame-spewing din, was an experience unreal enough. Through the window of the cabin, I could see the ground crew start back with wide-open mouths and hands over their ears, while, for my part, it was all I could do to hold on as the machine rocked under a ceaseless succession of explosions. I felt as if I were in the grip of some savage power ascended from the Nether Pit. It seemed incredible than Man could control it.

The Me 163 could attain speeds of up to 1,130 km/h, which meant that “the smallest error of judgement might mean the loss of the machine and [Hanna’s] own death”. Even correct judgement was no guarantee. Her test flight immediately suffered a crippling technical issue – the exposed undercarriage got jammed – and she couldn’t contact the towing plane to abort the test. She successfully flew the plane for a while, but as she attempted to land, the Me 163 stalled due to the protracted undercarriage, and she lost control and tumbled to the ground at over 240 kp/h.

We plunged, striking the earth, then, rending and Cracking, the machine somersaulted over — lurched — and sagged to a stop. The first thing I realised was that I was not hanging in my harness and therefore the machine was right-side up. Quite automatically, my right hand opened the cabin roof— it was intact. Cautiously, I ran my hand down my left arm and hand, then slowly along my sides, chest and legs. To my thankful amazement, nothing was missing and all seemed in working order.

She was wrong: her skull was shattered in six places, her upper jaw was displaced, and her nose was nearly torn away. “Each time I breathed, bubbles of air and blood formed along its edge.” With consciousness fading, Hanna found a pencil and pad and wrote a message explaining why the crash had occurred. She also tied a handerchief around her head so that the her rescue party wouldn’t see her face. It would be a long time before she would fly again.

Her dramatic crash made her a celebrity within the Nazi party, and it was here that she had her most intimate encounters with the inner machinery of the state. Some of it’s funny, like this sitcom-worthy encounter with Hermann Göring.

[Göring] planted his bulk squarely in front of me, his hands resting on his hips.

“What! Is this supposed to be our famous ‘Flugkapitän’? Where’s the rest of her? How can this little person manage to fly at all?”

I did not like the reference to my size. I made a sweep with my hand roughly corresponding to his girth.

“Do you have to look like that to fly?”

In the middle of my sentence, it suddenly struck me with hot embarrassment that, in the circumstances, my gesture might be considered out of place. I tried to halt it in mid-air, but too late — everyone, including Göring, had seen it and there was a great burst of laughter, in which Göring joined.

But mostly these conversations are unsettling, the way it’s unsettling to read a conversation involving a well-programmed chatbot that knows how to say the right things but is clearly non-human. History remembers most of the NSDP’s upper echelon as high-IQ sociopaths, men skilled at reforging reality using words – words that they didn’t truly mean at all.

As Hanna wines and dines with the inner circle of the Party, I was interested to learn about the rifts dividing Nazi Germany – particularly, the conflict between the “Gott Mit Uns” Protestantianism of the Prussian and Weimar eras, and the odd blend of pagan, atheistic, and social Darwinist thought of Heinrich Himmler.

In our family, we had always avoided mentioning the name of Himmler : my mother saw in him the adversary of Christianity and he could therefore have nothing in common with us.

Hanna eventually meets Himmler, and challenges him both on his anti-Christian beliefs and rumors she’s heard about his social policies. This is one of the few times Hanna expresses a political opinion.

We then turned to another problem, about which my feelings were strong, his attitude to women and marriage. I reproached him for looking at the matter from a purely racial and biological stand-point, considering woman only as a bearer of children and through his directives to the SS, about which, admittedly, I had only heard rumours, tending to undermine morality and destroy the sanctity of marriage.

These are probably references to Lebensborn, an SS-initiated breeding program that sought to improve Germany’s racial purity through abduction, insemination, and selective abortion.

Himmler replied to my charges factually and at considerable length. He assured me that he shared my views entirely. His policy had been misrepresented and misinterpreted, either unintentionally or from deliberate malice. It was very important, he said, that these tendentious rumours should not get about, particularly at the present time.

The real problem, Himmler explains, are people who spread rumors. He ends the conversation by thanking Hanna for her outspokenness (which is hard not to read as “you’re toeing the line, so don’t step across it”), and asking her to report all subsequent rumors to him.

But the elite Nazis aren’t just manipulative, they’re also delusional. At a second meeting with Göring (not long after her crash), Hanna is shocked to learn that he believes the Messerschmitt Me 163 to be ready for mass production. She argues with him at length – the plane is a dangerous toy, more likely to kill its pilot than an enemy – but he refuses to allow reality to disturb his illusions. German might and German industry will prevail. A German failure ontologically doesn’t exist. Certain people remained in this state of mind until Berlin crashed down around them.

To be blunt, I was soon asking the “naive or liar” question about Hanna herself. In 1944, she receives an a document by a friend in Stockholm, alleging something (we’re not told what, but can guess) about “gas chambers” in Germany. She queries Himmler about this:

I telephoned Himmler, obtaining permission to visit him at his headquarters in the field. Arrived there, I placed the booklet before him.

“What do you say to this, Reichsführer?”

Himmler picked it up and flicked over the pages. Then, without change of expression, he looked up, eyeing me quietly:

“And you believe this, Frau Hanna?”

“No, of course not.”

Was Hanna telling the truth here? She knew about Lebensborn. Did she not know about the Holocaust? It seems hard to believe. She was an important figure in the Vergeltungswaffe rocket program, which relied on slave labor in camps such as Auschwitz. For her have no idea whatsoever by 1944 is…interesting.

Whatever the case, 1944 is very late in the game. Soon everyone would know.

With the end fast approaching, Hanna became increasingly land-bound, serving in an advisory role to Luftwaffe forces on retreat from Stalingrad. She was a brilliant flyer but had zero skills as a soldier, to the point where she asks a German soldier to help her distinguish German shellbursts from Russian ones. There’s a pervasive grimness to this part of the book. Cities are falling. Critical resource centers and railhubs are being lost. The Russians are pushing west with overwhelming force. Every possible factor is working against the Reich.

There was only one way Germany could have achieved victory: a technological miracle. This was the last hope, that at the eleventh hour some brave scientist would shatter an atom in an interesting way, invent anti-gravity propulsion, or summon Himmler’s Norse gods down from Valhalla to do battle against the Asiatic hordes. This was what Germany needed to win – a Wunder-wuffe, or miracle weapon.

Spoiler: the miracle never occurred. Germany was defeated, and although World War II ended with a mighty science-conjured explosion, it didn’t flash to Germany’s benefit.

Hanna Reitsch was one of the final people to see Adolf Hitler alive. After a harrowing late-night flight into Berlin through heavy Russian flak (the entire city was under siege, and nobody knew if there was even an intact runway left for a landing), she arrived at the Reich Chancellery along with fighter ace Robert Ritter von Greim and then descended to the Fuhrerbunker.

Greim reported on our journey, Hitler listening calmly and attentively. When he had finished, Hitler seized both Greim’s hands and then, turning to me: “Brave woman! So there is still some loyalty and courage left in the world !”

But Hitler didn’t need more loyalty and courage from his followers. It was their loyalty and courage that had brought him to this point. It’s no credit to fight an insane war, nor obey insane orders, and Hanna’s mild questioning of Göring’s miracle planes was a thousand time more useful to the war effort than the blind obedience Hitler demanded from his followers.

He was an utter madman by that point, reality blasted from his brain and leaving only the shifting sand of hope and memory. He was Fuhrer of a nation that existed largely inside his own imagination. He “rewards” Greim by appointing him chief of the German air force…but Germany no longer had an air force to command!

But his life’s final decision was eminently sane: and agreeable to both his supporters and enemies alike.

On our second day in the Bunker, 27th April, I was summoned to Hitler’s study. His face was now even paler, and had become flaccid and putty-coloured, like that of a dotard. He gave me two phials of poison so that, as he said, Greim and I should have at all times “freedom of choice.” Then he said that if the hope of the relief of Berlin by General Wenk was not realized, he and Eva Braun had freely decided that they would depart out of this life.

Hanna ended up not using the phial of poison. She escaped the Fuhrerbunker, and survived well into the 1970s. Her death is a source of mystery and speculation – did she commit suicide using the phial in the end? I’m not so sure. She spent some time in American detention, and they certainly would have taken any means of suicide away from her.

The older ones had been through the First World War, you could tell it from their faces and their scars. After doing their duty for years in the trenches, they had returned home to be insulted and spat upon and have the shoulder-straps torn by hooligans from their uniforms. It was no wonder that their experiences had made them very embittered. “. . . Just as if it was us who had been the trouble-makers,” they said, almost in self defence, “—as if it was a positive pleasure to stop a Lewis gun bullet. . .”

This reminds me of the (possibly exaggerated) stories of Vietnam veterens getting spat on at LAX. It’s a damned sight easier to support the troops when they’re victorious troops. Soldiers from a lost war are often regarded with pity and even suspicion, like broken toys.

This was to be German’s legacy in World War II. Defeat, ruin, national shame, division, and a rebuilding enabled by the erasure of the past. It’s understandable, if only in hindsight, why Hanna cared so much about flying. There wasn’t damned thing worth having on the ground.

The title of the book seems uncannily appropriate. Hanna’s realm was the sky: one that lasted longer than a thousand years.

And now there is silence, everywhere. Earth and sky seem wrapped in sleep. My glider-bird slumbers, too, gleaming softly against the stars. Beautiful bird, that out-flew the four winds, braved the tempest, shot heavenward, searching out the sky, — soaring higher, as I am soon to learn, than any glider-plane has ever flown before.

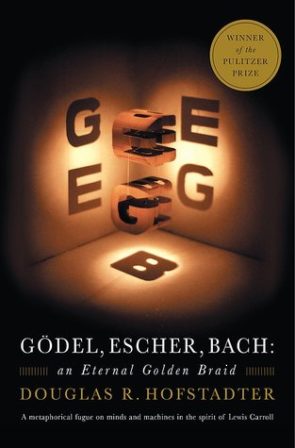

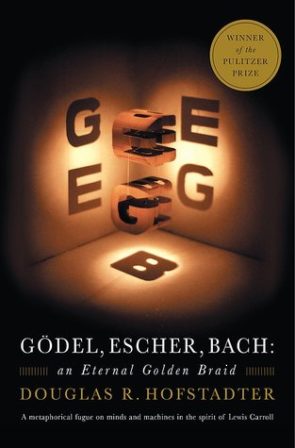

An 18th century German composer who wrote the theme for a king, with a principle melody that ascends yet remains trapped in tonal space. A 19th century Dutch artist who created maddening and hallucinatory artwork, defying intuition about perspective and reality. A 20th century German mathematician who described the limitations of a formal system addressing itself.

According to this book, Godel, Escher, and Bach were three blind men touching the same elephant: the Strange Loop.

“The “Strange Loop” phenomenon occurs whenever, by moving upwards (or downwards) through levels of some hierarchial system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started.”

You get on an elevator on floor 1, go up nine floors, emerge on floor 10, and then take the stairs back down. This is a loop. But imagine taking the elevator from floor 1 to floor 10, and the door slides open to reveal…floor 1. This is a strange loop.

“But things like that don’t exist.” They might not in architecture, but they do in the things that give rise to architecture: math, language, and human consciousness. Statements like “this sentence is a lie” and “I am nobody” are linguistic paradoxes. They’re like MC Escher’s Drawing Hands: destroying and recreating themselves over and over. Idioms like “pulling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps” are loopy. “This is not a pipe” is loopy. Barbershop poles are loopy.

One of the eye-opening parts of this book is how you start noticing strange loops all around you. The website you’re reading is powered by PHP, which stands for “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor”. This isn’t a mistake: the language’s name is an acronym containing its own acronym inside it! Like spiders, strange loops exist closer to your body than you think.

But there’s more to strange loops than weird art and logic puzzles. Hofstadter seems to be poking towards a theory of consciousness itself.

In 1996, David Chalmers explicated the two main problems of consciousness. 1) How does a collection of atoms develop a consciousness (meaning a subjective experience, an internal monologue, or whatever). 2) Why does this happen? Why don’t we experience the world the way a robot might?

Hofstadter’s sense (never forcefully argued) is that strange loops are responsible for the consciousness we experience. Just as the three letters “PHP” contains an infinite number of “PHPs” inside them, our three-pound brains are able to “unfold” into something more than the sum of its parts, via iterations of very complicated loops. This doesn’t address the second of Chalmers’ questions, although in a later book Hofstadter compares the soul to a “swarm of colored butterflies fluttering in an orchard” – something attracted by the fruit, but not a part of the fruit. The loops don’t require conscious experience, the conscious experience emerges as a kind of froth when all of these loops combine.

This implies that an algorithm would be capable of introspecting about its own existence. A string of math on a very large blackboard would perceive the color red, and feel pain. It’s a provocative idea, but don’t expect to find this formulated with a QED at the end. As the constant artistic motifs suggest, GEB isn’t a hard science book. This is probably why people actually read it.

GEB is filled with illustrations, games, puzzles, and – most notoriously – dialogues inspired by Lewis Carroll. Some of these are astonishingly creative. The passage about the crab canon made me stop reading for a moment, because it was incredible, and I wanted to be able to remember it instead of immediately forgetting. It was mind expanding. Nearly mind-exploding.

Although GEB contains a primer on the basics of computer language, intellectual rigor isn’t the book’s goal. One of Hofstadter’s many interests is Zen Buddhism, which is our culture’s most potent form of anti-logic and as such is of interest to the student of the strange loop.

When the nun Chiyono studied Zen under Bukko of Engaku she was unable to attain the fruits of meditation for a long time. At last one moonlit night she was carrying water in an old pail bound with bamboo. The bamboo broke and the bottom fell out of the pail, and at that moment Chiyono was set free! In commemoration, she wrote a poem:

In this way and that I tried to save the old pail / Since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break / Until at last the bottom fell out. / No more water in the pail! / No more moon in the water!

Zen never makes lessons easy for the student: you’re the one who has to do the work and become cosmic. But GEB makes the road far more fun than it has to be. What stands out about Hofstadter’s prose is how readable it is. Hofstadter isn’t a wordsmith, he’s a word alchemist, making dull things sparkle. The prelude to my edition contains a digression in the difficulties he had typesetting the book, which sounds as gripping as Hannibal crossing the Alps. (There’s also a somewhat cringeworthy part self-flagellating about the how the original printing of the book uses the default male voice.)

So is “loopiness” the way a collection of atoms can collectively seem to think, reason, and experience? The book leaves me unsure, as I think it was meant to. It’s the world’s longest Zen koan, fragments of information that never coalesce into a hard idea, but seem to get me closer to enlightenment than I was before.

Interesting aside: Godel, Escher, and Bach are three wise men (initials GEB), also the three wise men of the Nativity tale are Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar (initials GMB), also M is E rotated 90 degrees, also they brought gift of gold, frankencense, and myrrh (initials GFM), also F is the letter after E in the Roman alphabet, also “Godel” is nearly an anagram of “gold”, also I lied when I said this part was interesting.